outreach

CLI MATE

formerly COIN

European Perceptions

of Climate Change (EPCC)

Socio-political profiles to inform a cross-national

survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

June 2016

About the EPCC project

The European Perceptions of Climate Change Project (EPCC) is coordinated by Cardiff

University and forms part of the Joint Project Initiative-Climate Change (JPI-Climate -

see www.jpi-climate.eu), a research programme uniting National Research Councils

across Europe. Inter-disciplinary teams from the UK, Germany, France and Norway are

individually funded to collaborate in the design and analysis of a major comparative survey

of climate and energy beliefs amongst the public in these 4 participating nations.

This research project has been supported through JPI Climate Programme and associated

grants from Cardiff University Sustainable Places Research Institute, School of Psychology

and the Economic & Social Research Council, ESRC (ES/M009505/1).

This research project has been co-funded by France’s Agence Nationale de la Recherche

under grant n° ANR-14-JCLI-0003.

This research project has been funded under the KLIMAFORSK programme of the

Norwegian Research Council (NFR; project number 244904).

This research project has been funded under the cooperation agreement between Statoil

and the University of Bergen (Akademiaavtale; project number 803589).

The research project has been funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and

Research (funding code: 01UV1403).

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the members of our International Stakeholder Advisory Panel:

Ewan Bennie, Department for Energy and Climate Change

Nick Molho, Aldersgate Group

Christian Teriete, Global Climate Change Alliance / European Climate Foundation

Caroline Lee, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development / International

Energy Agency

Tom Brookes, European Climate Foundation

Henri Boyé, Former Environment and Sustainable Development Council

Anders Nordeng, Thomson Reuters Point Carbon

Nils Tore Skogland, Friends of the Earth Norway

Karen Louise Nybø, Hordaland County Council

Sølve Sondbø, Hordaland County Council

Christopher Brandt, Climate Concept Foundation

Manfred Treber, Germanwatch

Project team

Authors

Cardiff University, UK (Coordinator)

Nick Pidgeon, Lead Investigator - PidgeonN@cardiff.ac.uk

Wouter Poortinga - PoortingaW@cardiff.ac.uk

Katharine Steentjes - Steentjes[email protected]

Climate Outreach, UK

Adam Corner - adam.corner@climateoutreach.org

Institut Symlog, France

Claire Mays - claire.mays@gmail.com

Marc Poumadère - [email protected]

Rokkan Centre for Social Studies, Norway

Endre Tvinnereim - Endre.Tvinner[email protected]

University of Bergen, Norway

Gisela Böhm - [email protected]

University of Stuttgart, Germany

Annika Arnold - [email protected]

Dirk Scheer - [email protected]

Marco Sonnberger - [email protected]

Editing & Production

Anna MacPhail, Project Coordinator, Climate Outreach - anna.macphail@climateoutreach.org

Olga Roberts, former Project Coordinator, Climate Outreach

Elise de Laigue, Designer, Explore Communications - elise@explorecommunications.ca

About Climate Outreach

Climate Outreach (formerly COIN) is a charity focused on building cross-societal

acceptance of the need to tackle climate change. We have over 10 years of experience

helping our partners to talk and think about climate change in ways that reect their

individual values, interests and ways of seeing the world. We work with a wide range

of partners including central, regional and local governments, charities, business, faith

organisations and youth groups.

The Old Music Hall, 106-108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

+44 (0) 1865 403 334 @ClimateOutreach

[email protected] Climate Outreach

www.climateoutreach.org Climate Outreach

Cite as: Arnold, A., Böhm, G., Corner, A., Mays, C., Pidgeon, N., Poortinga, W., Poumadère, M., Scheer, D., Sonnberger, M.,

Steentjes, K., Tvinnereim, E. (2016). European Perceptions of Climate Change. Socio-political proles to inform a cross-

national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK. Oxford: Climate Outreach.

Cover photos by johndal and Kristian Buus.

JUNE 2016

in

f

@

Contents

Executive summary............................................................................................................................... 5

France .................................................................................................................................................................6

Germany ............................................................................................................................................................. 7

Norway ............................................................................................................................................................... 8

UK ........................................................................................................................................................................9

Key concepts to inform the survey design .........................................................................................10

Climate & energy in context .........................................................................................................................10

National energy policies ................................................................................................................................ 10

Media & other cultural inuences .................................................................................................................11

Climate impacts ................................................................................................................................................11

Personal engagement .....................................................................................................................................12

Climate scepticism & environmentalism ....................................................................................................12

Introduction: climate change and the European public ....................................................................13

France: A socio-political prole .......................................................................................................... 16

Historical, cultural and policy context.........................................................................................................16

Key actors in the French context ................................................................................................................ 20

Key climate and energy-related events in France ...................................................................................25

Anticipated consequences of climate change in France ........................................................................28

Media reporting in France .............................................................................................................................28

Germany: A socio-political prole ......................................................................................................31

Historical, cultural and policy context.........................................................................................................31

Key actors in the German context ............................................................................................................... 33

Key climate and energy-related events in Germany ...............................................................................36

Anticipated consequences of climate change in Germany ....................................................................38

Media reporting in Germany ........................................................................................................................39

Example for illustration: Coal extraction in Germany .............................................................................42

Norway: A socio-political prole ....................................................................................................... 43

Historical, cultural & policy context ...........................................................................................................43

Key actors in the Norwegian context .........................................................................................................45

Key climate and energy-related events in Norway .................................................................................49

Anticipated consequences of climate change in Norway ..................................................................... 50

Media reporting in Norway ...........................................................................................................................51

Norway and COP21 .........................................................................................................................................51

UK: A socio-political prole ............................................................................................................... 53

Historical, cultural & policy context ...........................................................................................................53

Key actors in the British context .................................................................................................................. 57

Key climate and energy-related events in the UK ...................................................................................59

Anticipated consequences of climate change in the UK .........................................................................61

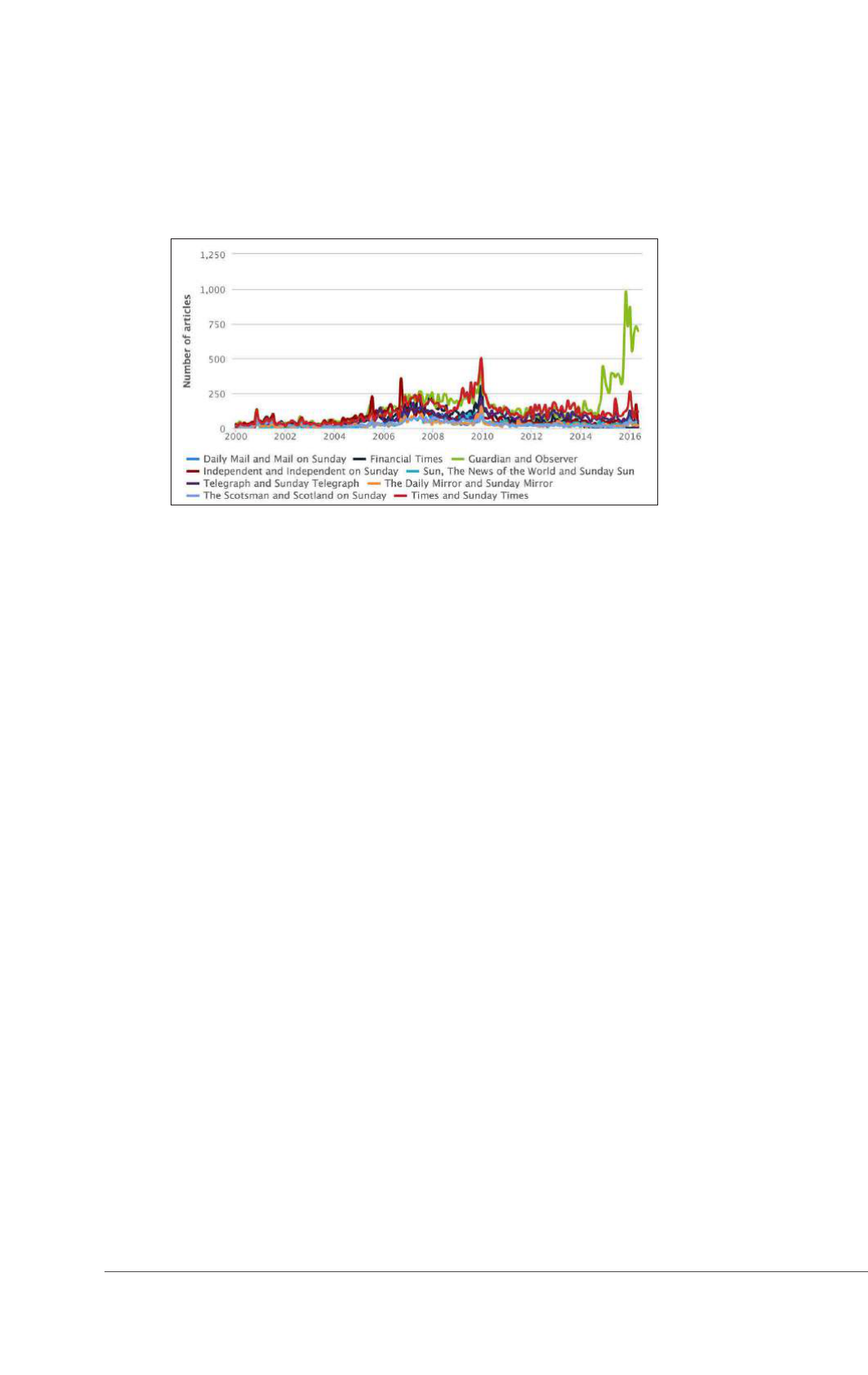

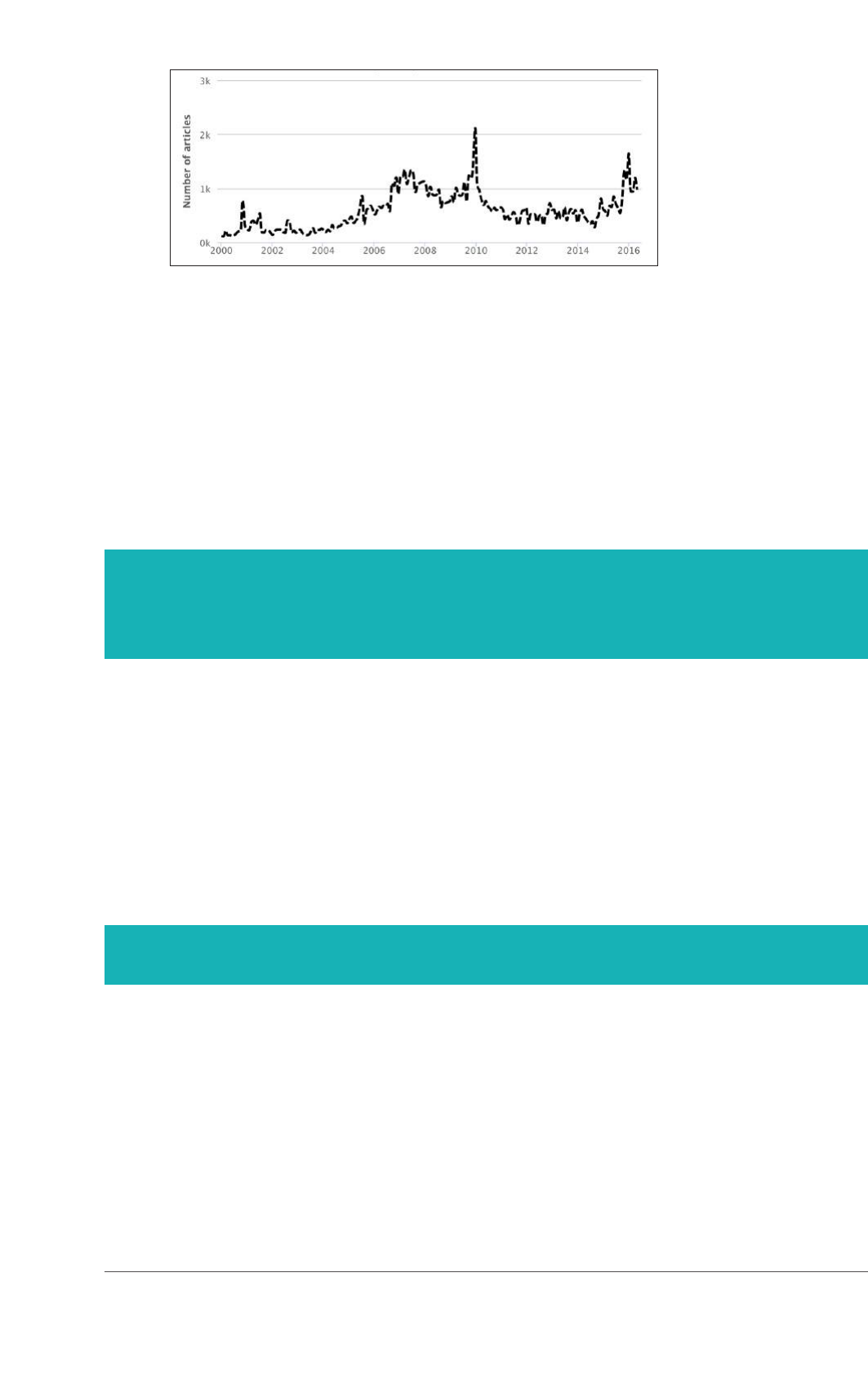

Media reporting in the UK ..............................................................................................................................61

UK and COP21 .................................................................................................................................................66

References ........................................................................................................................................... 67

5

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

Executive summary

‘European perceptions of climate change’ (EPCC) is a two-year project, with the central

aim of designing and conducting the rst ever theoretically grounded cross-national

survey of public perceptions of climate change and energy transition in Europe. EPCC is

a collaboration between academic teams in four participating nations (France, Germany,

Norway and the UK, led by Nick Pidgeon at Cardiff University) and Climate Outreach, a

UK-based think tank which specialises in climate change communication.

The purpose of this discussion paper is to provide a detailed overview of the socio-

political context in each of the four participating nations. A key feature of the EPCC survey

is that its design was directly informed by these national ‘proles’, as well as by an ongoing

process of stakeholder engagement with an international advisory panel. Following a

general introduction outlining the pan-European context, the paper presents four separate

national analyses, each organised into ve sub-sections:

y The historical, cultural & policy context in each nation;

y Key actors shaping public perceptions of energy and climate change in each nation;

y Key climate and energy-related events that have taken place so far;

y The anticipated consequences of climate change in each nation;

y Media reporting on energy and climate change.

Because the analyses are quite detailed, we also provide in the next four pages a very brief

summary of the key issues relating to each of the four nations in this Executive Summary,

and identify Key Concepts (arising from these analyses) which inform the survey design

(also highlighted throughout the document in blue boxes). In this way, we seek to make the

links between the different components of the project clear. These key aspects informed

the design of the EPCC questionnaire, alongside detailed study of the literature of previous

surveys, and our own stakeholder consultation process.

6

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

France: summary of key issues

y France has low GHG emissions per capita relative to

other European and developed nations. This is largely

due to the fact that the electricity production is mainly

nuclear. Legislation voted in 2015 will reduce French

reliance on nuclear energy from an average of 75% of

the electricity mix to 50% by the year 2025. Moreover

there is a target to reduce total energy consumption by

50% by 2050.

y France hosted the COP21 meeting in Nov-Dec. 2015

and Conference president Laurent Fabius won high

esteem for successfully leading the parties to a strong

and historic agreement. After the record-breaking

signature of the Paris Agreement by 175 parties on Earth Day in April 2016, successor

president and Ecology Minister Ségolène Royal announced 12 decrees or decisions

advancing specic mitigation actions in France.

y The dense network of territorial government units is recognised and encouraged in

national governmental discourse as a major actor in climate change adaptation.

y NGOs and civil society organisations are increasingly represented in state consultative

bodies discussing measures to mitigate climate change.

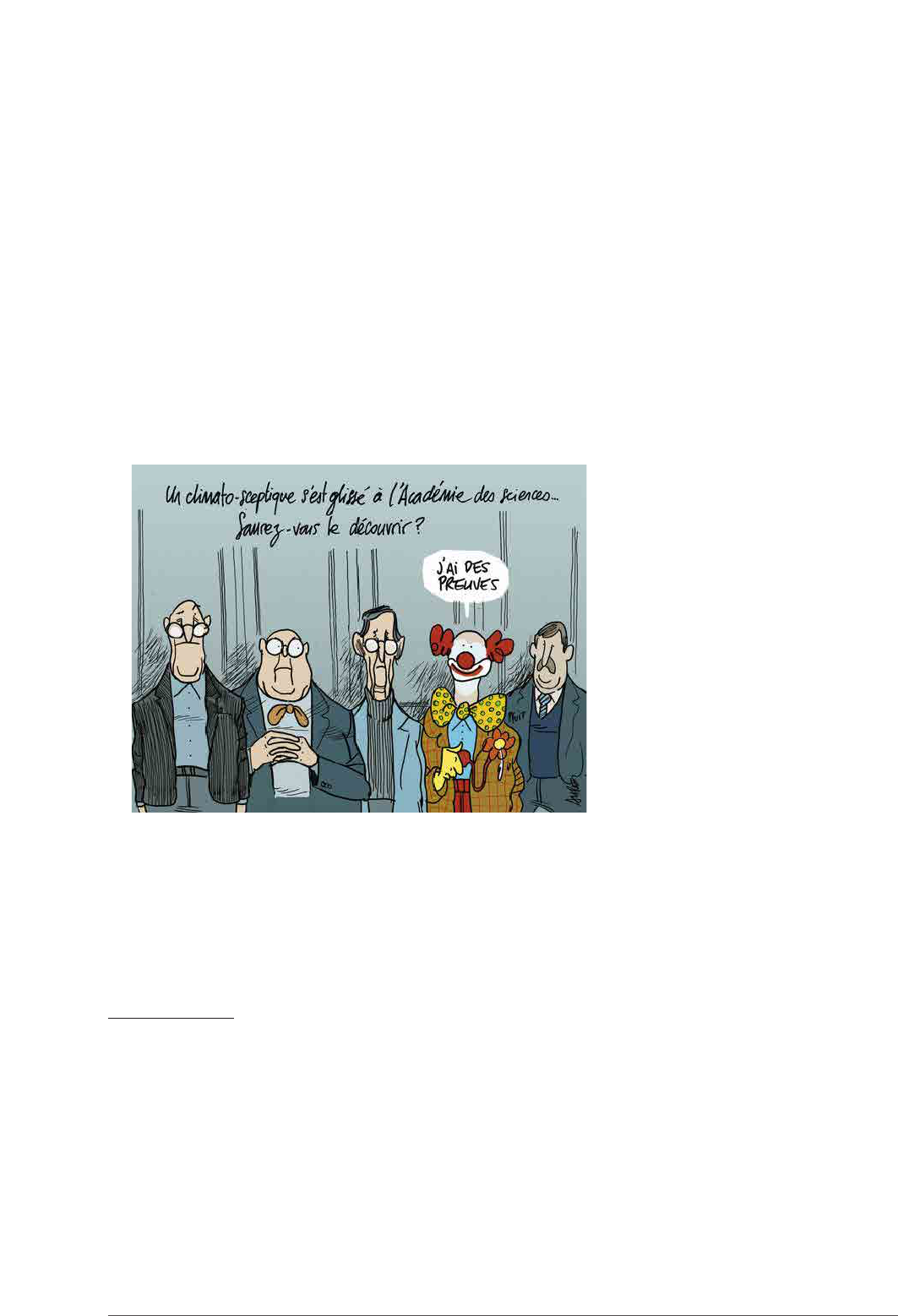

y The French Academy of Sciences includes a very small fringe of scientists who deny

climate change which at times can gain a disproportionate presence in the media.

y France is a culturally and historically Catholic country. Pope Francis’ June 2015

environmental encyclical calling on all religions to take action on climate change was

taken note of in France.

y France is projected to experience more frequent and longer periods of heatwaves

(potentially fatal to at-risk populations – the elderly, infants, the chronically/gravely ill

etc.) and droughts.

The Scandola Nature Reserve

is located on the west coast of

the French island of Corsica,

within the Corsica Regional

Park. The park and reserve

were added to the UNESCO

World Heritage List in 1983.

Photo: orangebrompton

7

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

Germany: summary of key issues

y The history of public engagement with energy and

climate change in Germany has been strongly shaped

by major public protests against nuclear energy. These

started in the 1970s and continued well into 2000s,

resulting in a nuclear phase-out before 2022.

y The level of environmental awareness is traditionally

high among German citizens. In 1983 the Green Party

entered the German Parliament for the rst time and

was part of the governing coalition between 1998 and

2005. In the 2014 survey on environmental awareness in

Germany, respondents ranked environmental protection

as fth among a list of the most important social issues

currently facing Germany.

y Climate scepticism is not considered a serious problem in Germany. A national survey

in 2014 reported that only 7% of respondents could be considered ‘trend’ or ‘attribution’

sceptics, only 8% as ‘consensus’ sceptics and only 5% as ‘impact’ sceptics.

y Politically, climate and environmental issues are closely related to the intended

transition of the energy system in Germany (‘Energiewende’). This transition aims at

meeting national energy demands by at least 60% of renewable energy by 2050.

However, brown and black coal are still important energy sources in Germany. The

coal extraction industry not only serves as an important employer in Germany but also

forms a part of regional identities.

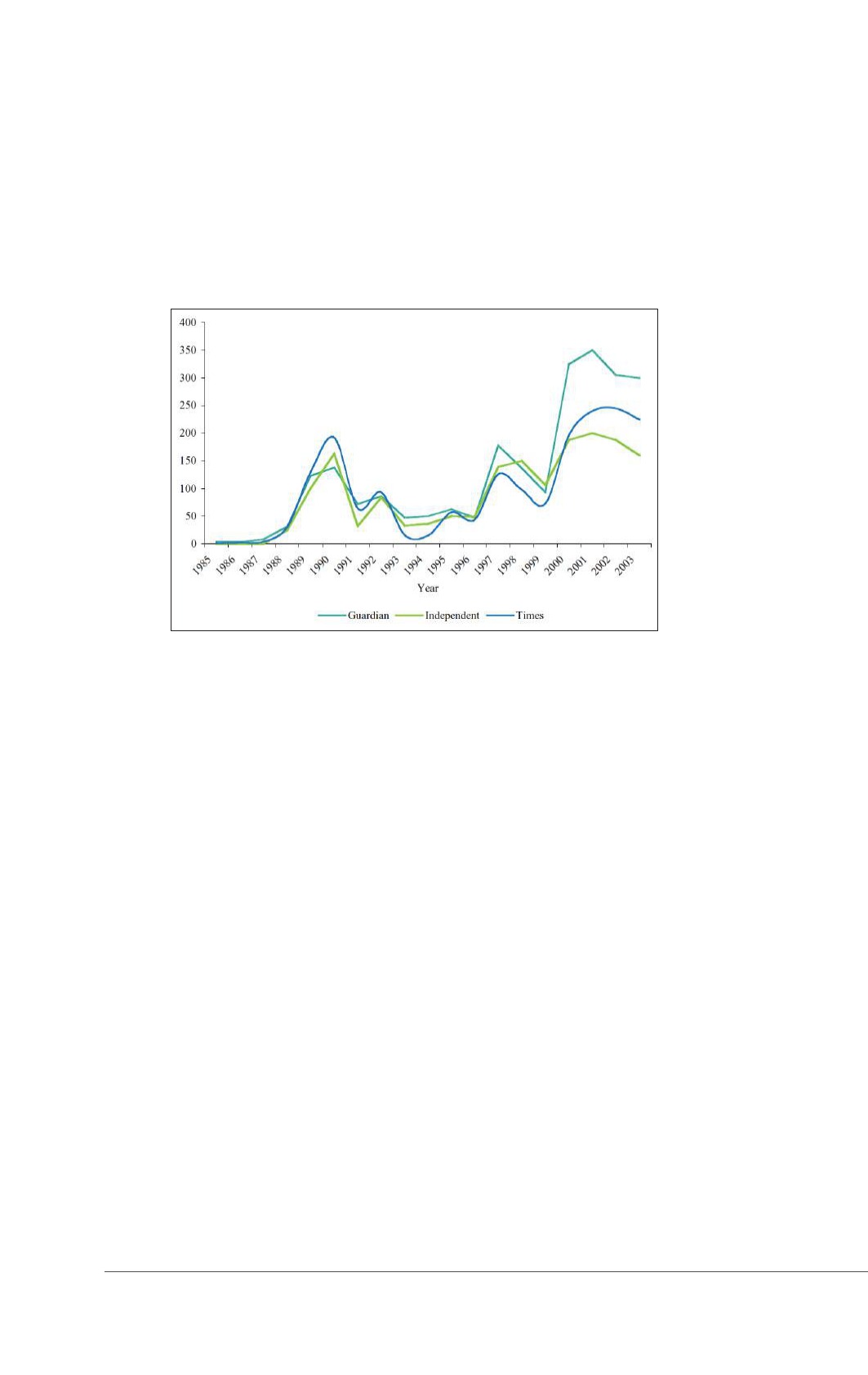

y Climate change is a prominent issue in German news coverage, occurring frequently

as the main cover story in magazines and newspapers. In 1986, Der Spiegel – one of

the main news magazines in Germany – published an edition introducing the climate

catastrophe with a ctional cover picture showing the Cologne Cathedral being ooded.

y According to current models, the impacts of climate change will mostly be moderate

in Germany. The economy, especially agriculture in eastern Germany and those regions

that depend on winter tourism will be affected by rising temperatures.

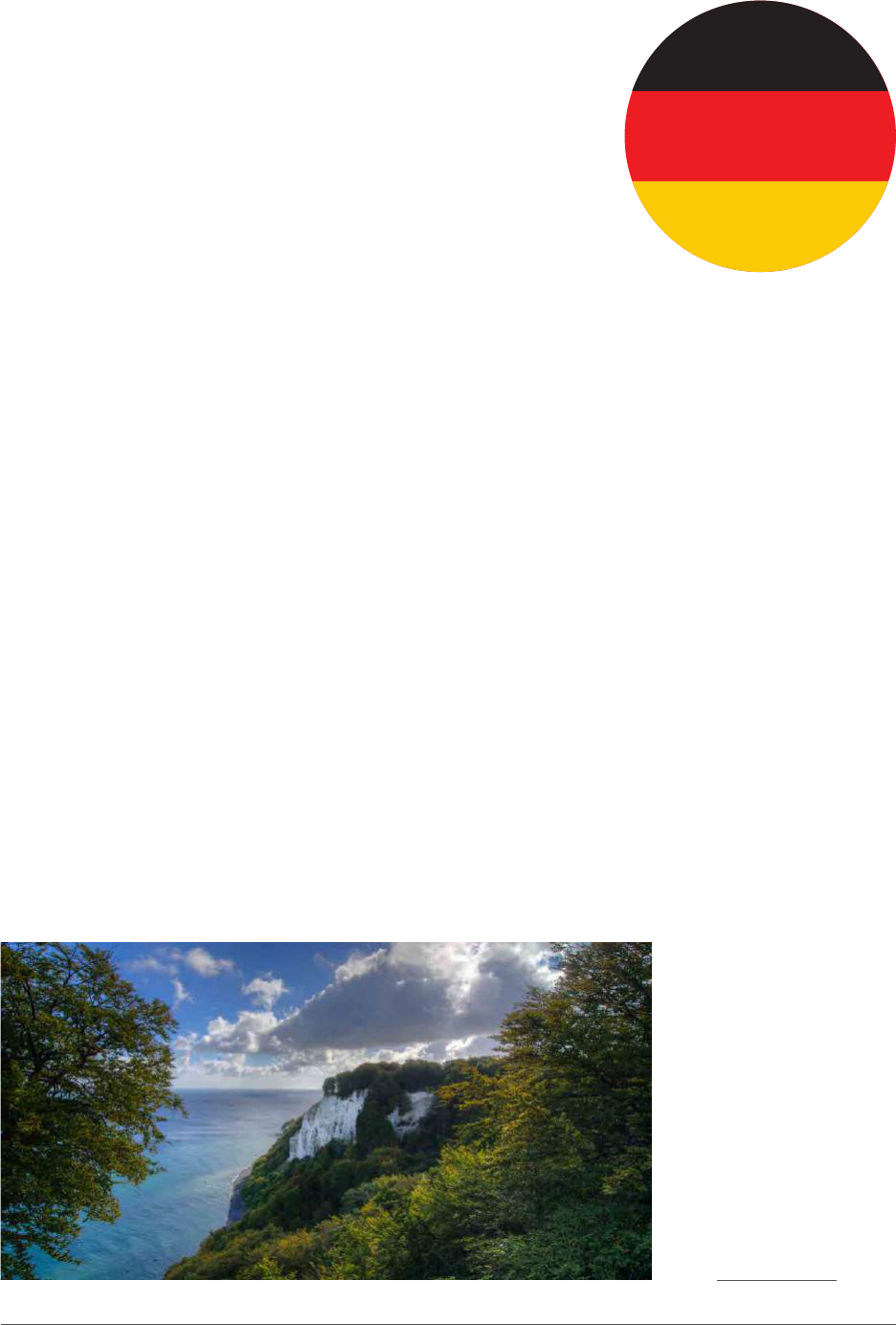

The Jasmund National Park

is a nature reserve in the

Jasmund peninsula, in the

northeast of Rügen island in

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern,

Germany. It was added to the

UNESCO World Heritage List

in 2011 as an extension to the

Primeval Beech Forests of the

Carpathians and the Ancient

Beech Forests of Germany.

Photo: Pablo Necochea

8

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

Norway: summary of key issues

y Oil and hydroelectric power play important roles in

Norwegian society, as key providers of employment and

energy. While the country’s GHG emissions are close to

the European average at about 11 tonnes CO

2

e/capita

per year, Norway’s emissions prole is unusual, with

essentially zero emissions from power production but high

emissions from oil and gas extraction in the North Sea.

y The economic importance of the fossil fuel and

hydropower sectors blends with social identity and

conceptions of nature to form powerful narratives

around how Norway found and exploited its offshore oil

and gas resources.

y National and international companies, the central government bureaucracy, business

and labour associations and NGOs seek to further their own interests in debates over

the future of fossil fuel exports versus renewable energy and climate protection in the

future. ‘Cognitive dissonance’ emerges because the country seeks a climate-friendly

image at home and abroad, while being unable to curb its domestic emissions and

maintaining fossil fuel exports at relatively high levels.

y Unlike countries such as the US and Australia, climate change is not considered

primarily as a left-right issue in Norway, and Norway does not have any signicant

climate sceptical news outlets.

y Norway’s most important mitigation policies are the EU emissions trading scheme,

strong support for electric vehicles and overseas aid to reduce tropical deforestation.

y Heavier rainfall, more frequent landslides and heavier oods are likely to result from

climate change as average annual temperatures are expected to increase by about

4.5ºC (range: 3.3 - 6.4ºC) and annual precipitation by about 18% (range: 7 - 23%).

Norway is set to experience less snow and glaciers will shrink or disappear.

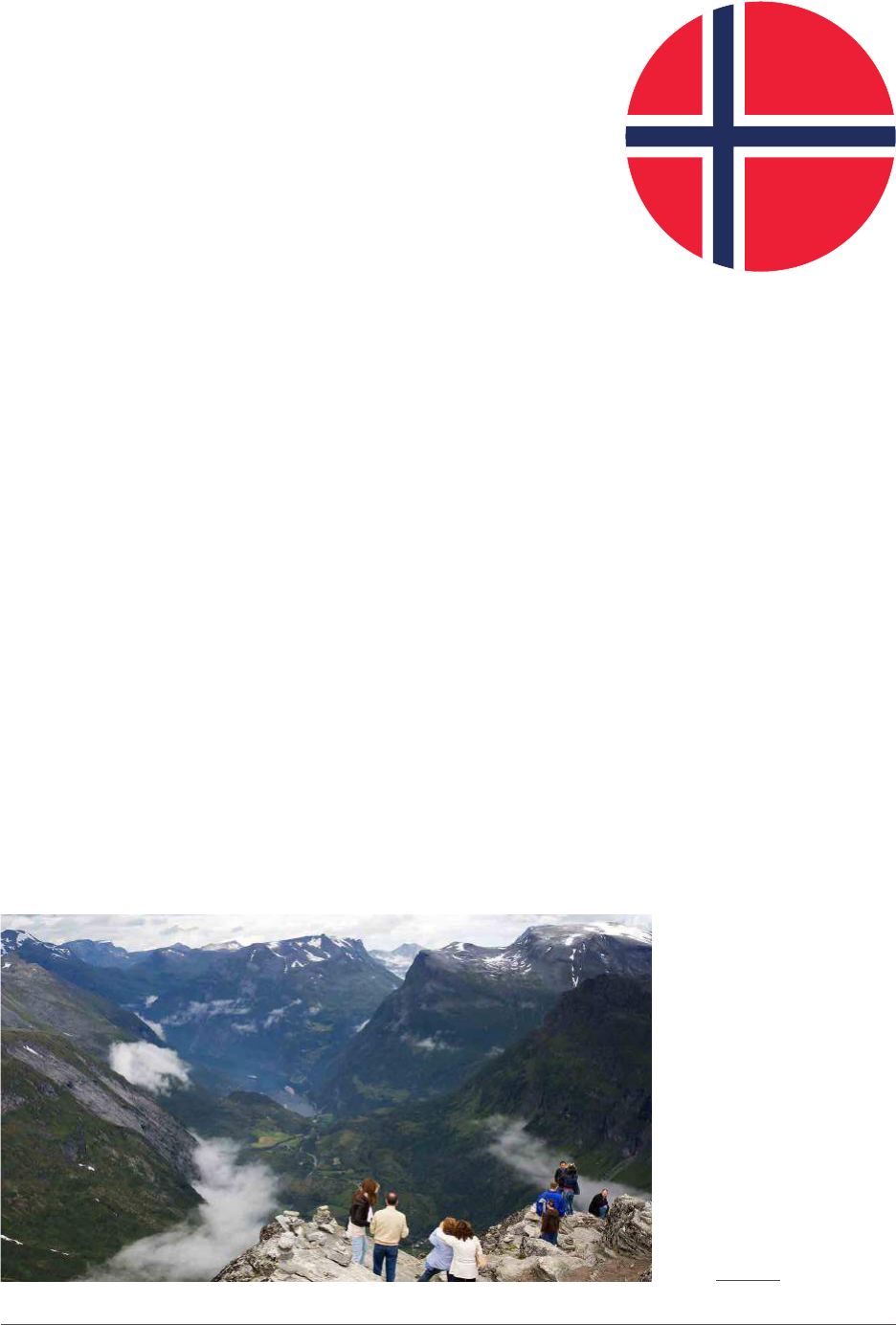

The Geiranger Fjord is a fjord in

the Sunnmøre region of Møre

og Romsdal county, Norway. It

was listed as a UNESCO World

Heritage Site in 2005, jointly

with the Nærøyfjorden.

Photo: Whuups

9

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

UK: summary of key issues

y The industrial revolution, the discovery of North Sea oil

and an ambivalent/unsettled relationship with nuclear

power are key issues in the historical background of the

UK in relation to energy.

y A broad cross-party consensus on climate change led

to a world-leading Climate Change Act (2008), and the

instalment of the Committee on Climate Change to track

the progress towards an 80% emission reduction by 2050.

y Media analysis has identied scepticism in the media to

be primarily an Anglophone phenomenon with sceptics

views given more presence in the US and UK media than

in other countries.

y The UK ‘political sector’ has a history of framing nuclear power as a solution to climate

change, while public perception research identies a consistent preference for

renewable energy among the UK public (Spence et al. 2010).

y The current conservative government announced the phase-out of subsidies for

onshore wind farms and solar systems, and continues to support the development of

shale gas, North Sea oil and gas, and nuclear power.

y In 2015 the government received criticism from UN scientists and business analysts for

‘sending mixed signals’ with regards to the support for low-carbon technologies and

solutions in the UK.

y Climate change is expected to increase the risk of severe ooding and hotter summers

in the UK, with potential opportunities (e.g. for the agricultural sector).

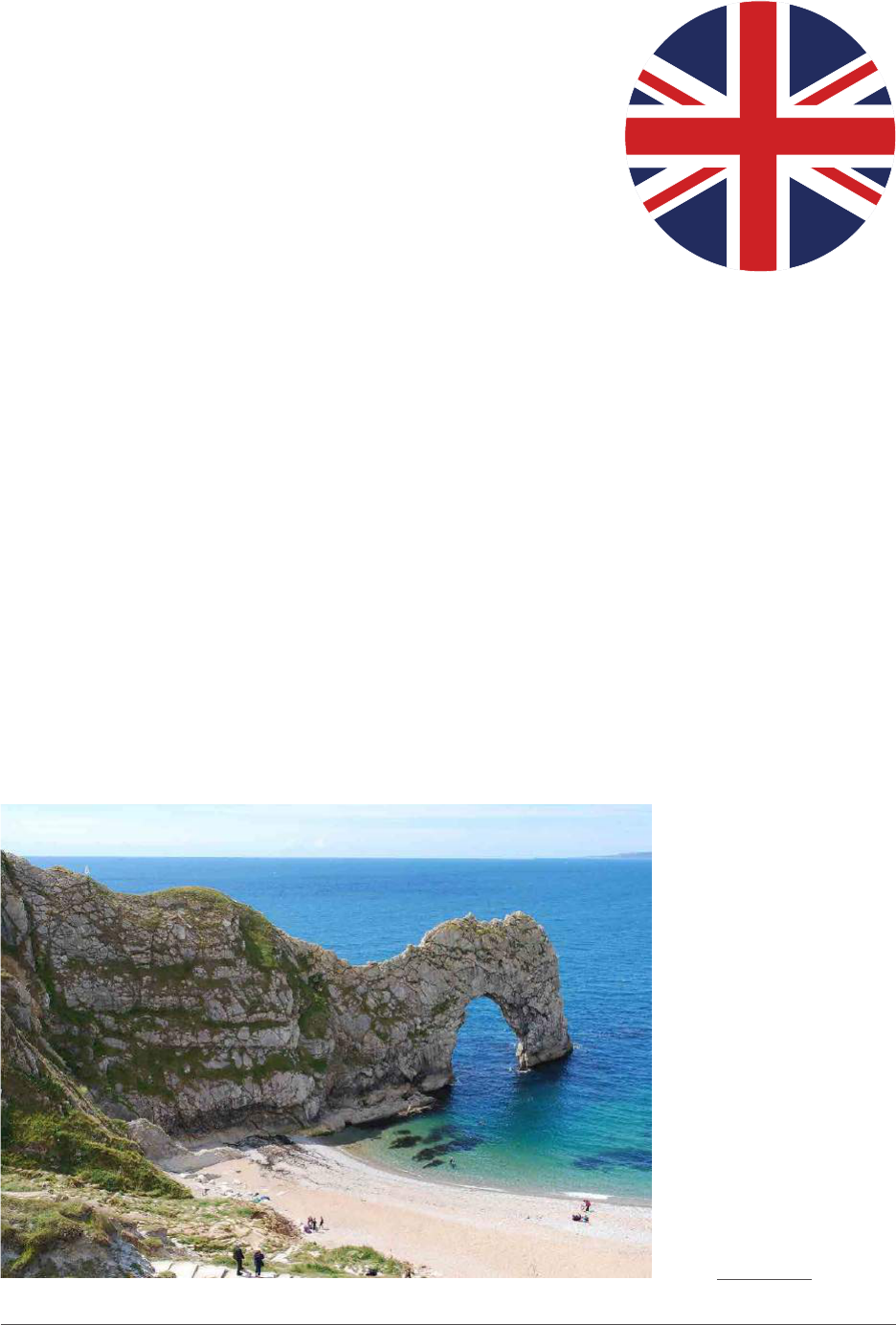

The Jurassic Coast covers 95

miles of stunning coastline

from East Devon to Dorset,

in Southern England. It was

added to the UNESCO World

Heritage List in 2001.

Photo: GaryW2008

10

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

Key concepts to inform

the survey design

The purpose of completing these socio-political analyses was to provide – in conjunction

with the advice and guidance of the stakeholder panel – a robust and practically-grounded

evidence base with which to inform the design of the survey. By situating the design of

the EPCC survey in stakeholder views and an analysis of the socio-political context in

each participating nation, the project aims to go beyond simply documenting differences

between European publics on climate change, and say something about why these

differences are apparent. Throughout the document, key concepts which have, in addition

to theoretical considerations, informed the survey design are highlighted in blue boxes. In

this section we summarise them for ease of reference.

The EU’s central position in the global climate change policy debate may impact on

European publics in a number of ways. On the one hand, the (relatively) high prole

leadership provided by the EU at a global level may act as a cue for European citizens

to take climate change more seriously. But it is also possible that the centrality of

climate change to the EU could mean that the issue of climate change is conated

with the ‘European Project’ – and all the negative connotations that this has for some

European citizens.

The political attention given to the global economic recession, the serious impacts

it has had on European citizens’ lives, and the ongoing challenges that people face

in terms of employment and income are highly likely to detract from the relative

perceived importance of issues like climate change.

In response to the discussion around climate change migration sparked by the current

refugee crisis in the EU, our research could assess the perceived link between climate

change and migration and concern about ‘climate change victims’.

Climate & energy in context

The EPCC survey will be able to shed light on the relationship between political

ideology and views about energy and climate change in the four participating nations,

as well as differences in views emerging from a classical ‘environmentalist’ tradition of

thought, and more ‘technologically optimistic’ perspectives.

Climate scepticism is a largely Anglophone phenomenon (in terms of media coverage

and public perceptions), and is therefore likely to be higher in the UK than in other

participating nations. The concentration of climate sceptical views in the media may

also lead to a higher political polarisation than in the other countries.

Climate scepticism & environmentalism

11

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

KEY CONCEPTSKEY CONCEPTS

Although the EPCC study cannot monitor media discourse and volume in detail, our

analysis of survey results will be attentive to this as a possible factor in any changes in

perceptions (within each nation, and whether these track trends in media coverage)

and between the four nations.

Perceptions of political inaction may increase the sense among some citizens that “the

impact of climate change was exaggerated by climate scientists as well as the media”

(Ryghaug et al., 2011, p. 790). This should be seen in connection with the fact that trust

in the state is much stronger in Norway than in many other countries.

A widespread feeling of national environmental identity (being associated with the

green landscape) might be able to explain attitudes towards renewable energy – we

will be able to explore whether the four countries dene their national identity in the

same way and how that affects their attitudes towards climate change policies.

Media & other cultural influences

There are likely to be differences in the national climate and energy ‘self-identity’ of

EU members who are ‘producers’ of energy and those who are primarily ‘consumers’

of it. There is an important question about whether these sorts of dynamics impact

on public perceptions of energy and climate change – and how comparisons with the

energy and climate policies of other EU states may inuence national perceptions.

The EPCC survey will be able to compare levels of support for fossil fuels between

the four participating countries, both now and into the future. There may be regional

differences within nations (e.g. in the UK, on perceptions of North Sea oil).

The decision to phase-out nuclear energy and the transition to an energy system

mainly based on renewables is one of the most important aspects of German

environmental policy, and the EPCC survey will be able to compare public views on

the components of the Energiewende with attitudes towards renewables in the other

participating nations.

There are likely to be important differences in perceptions of nuclear power, for

example in the way that the technology is ‘framed’ (as a ‘low-carbon technology’), and

in different national response to the Fukushima disaster.

National energy policies

12

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

KEY CONCEPTSKEY CONCEPTS

The EPCC survey will be able to compare levels of perceived need for ‘personal’ or

‘domestic’ activity to limit the effects of climate change, and assess whether they differ

across the four participating nations.

Do per capita emissions relate to the four nations’ public perspectives on climate

change and energy use?

The EPCC survey will be able to compare emotional and affective reactions to climate

change and energy system change in the four participating nations.

Trust in the state is much stronger in Norway than in many other European countries.

The EPCC survey will be able to compare levels of trust in policy actors, and perceived

policy action/inaction.

The EPCC survey will include items that help explore the factors underlying this

tension, which may derive from a conict between classical environmentalist and

technologically optimistic strands of thought.

While levels of climate change scepticism have been low over the last few years the

presence of climate change sceptic views in the UK media landscape might lead the

public to underestimate how many people consider climate change in their daily lives.

Personal engagement

The EPCC survey can identify whether perceptions of the seriousness of climate

impacts in four participating nations differ, and whether these differences have any

relation to the actual projected impacts of climate change in each nation. Where are

there potential ‘opportunities’ from climate change for individual nations and will this

impact on public perceptions of climate risks?

People in areas more likely to be affected by climate impacts (and/or people who

indicate previous experience with climate change impacts) might perceive climate

change to be less of a ‘distant’ issue, which might lead to higher concern about climate

change and more willingness to engage in related behaviours (differences may emerge

between or within participating nations).

The UK public might be more positive about the national impacts of climate change

compared to people in (e.g.) France due to the potential opportunities for the UK.

Climate impacts

13

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

In April 2016, 175 parties (174 countries plus the EU, which represents 28 countries) signed

up to the Paris Climate Agreement. The Agreement itself had been agreed at the summit

held in Paris at the end of 2015. Whilst the Paris summit did receive media attention

across Europe, it’s important to note the quantity of the coverage wasn’t as high as that

of the Copenhagen conference in 2009. The quality of the reporting, however, was much

more positive, and negotiators were able to get across a good news message about the

outcomes of the summit.

1

This sense of optimism has been carried through to the signing of

the Paris Climate Agreement.

For the EU, the climate negotiations in Paris were a diplomatic success, aligning global

ambition on climate policy with the EU’s longstanding call to limit global warming to an

average of 2 degrees celsius.

2

As part of its commitment to the 2°C limit the EU has set a

climate target of reducing emissions by at least 40% by 2030. However, up to now that

target has only been a statement of intention. The EU has held off implementing legislation

in the run up to the Paris summit because the steps needed to meet the targets are deeply

contested by some member states. Subsequent to the signing of the Paris agreement the

EU now has to push forward with agreeing the required policies needed to deliver these

cuts. This potentially divisive process will be taking place against a backdrop of other

threats to EU unity. In addition, the challenge of implementing this climate legislation is

exacerbated by the introduction at the Paris summit of a possible 1.5°C target for warming,

which may require the EU to either bring forward the date by which the cuts will be

achieved or strengthen the target itself.

3

In the context of this crucial moment for European climate policy, the EPCC project

addressed a signicant knowledge gap with regard to European public engagement with

climate change. While there have been national polls of EU member states and occasional

cross-European surveys of public opinion (most notably the ‘Eurobarometer’ series which

has sometimes included items relating to climate change), there is very little evidence on

how citizens in different European nations differ on engagement with climate change.

By grounding the design of the EPCC survey in stakeholder views and an analysis of

the socio-political context in each participating nation, the project aims to go beyond

simply documenting differences between European publics on climate change, and say

something about why these differences are apparent. The focus of the current discussion

1 Pashley, A. (2016). Why did Paris climate summit get less press coverage than Copenhagen? Climate Home. Online: http://www.

climatechangenews.com/2016/03/07/why-did-paris-climate-summit-get-less-press-coverage-than-copenhagen/

2 Geden, O. and Droge, S. (2016). After the Paris Agreement - New Challenges for the EU’s Leadership in Climate Policy. German

institute for International and Security Affairs. Online: http://www.isn.ethz.ch/Digital-Library/Articles/Detail/?id=196630.

3 ibid

Introduction: climate change

and the European public

14

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION

paper is on the ways in which key events, inuential actors, media and the wider cultural/

historical and policy context in the four participating nations may impact on public

engagement with climate change.

The European Union (EU) itself, and notably the European Commission, is an important and

unusual actor at a pan-European level in terms of setting the agenda on climate change. As

a longstanding, well-established and relatively stable regional grouping, it has historically

been a leading voice advocating for policies to mitigate and adapt to climate change

(Rayner & Jordan, 2013; Tvinnereim, 2013). In rhetoric and in policy ambition, the EU has

tended to position itself as a world leader on climate change. The EU has committed to

spending at least 20% of its €960 billion budget for the 2014-2020 period on climate

change-related policies. And even if the ambitions of EU directives have not always

resulted in proven policy efcacy or inuence on other key global actors (Jordan et al,

2010), it has been argued that “the EU can be looked upon as a rather benign ‘critical case’:

if [it] cannot develop effective climate policies, then the implications for the globe are grim”

(Wettestad, 2000).

However, while there are clearly important inuences which might be expected to operate

at a pan-European level, every European nation has a different social, political, historical

and cultural context which shapes public engagement with climate change.

There are likely to be differences in the national climate and energy ‘self-identity’ of

EU members who are ‘producers’ of energy and those who are primarily ‘consumers’

of it. There is an important question about whether these sorts of dynamics impact

on public perceptions of energy and climate change – and how comparisons with the

energy and climate policies of other EU states may inuence national perceptions.

The EU’s central position in the global climate change policy debate may also impact

on European publics in a number of ways. On the one hand, the (relatively) high

prole leadership provided by the EU at a global level may act as a cue for European

citizens to take climate change more seriously. But it is also possible that the centrality

of climate change to the EU could mean that the issue of climate change is conated

with the ‘European Project’ – and all the negative connotations that this has for some

European citizens.

While it is not within the scope of this paper to document in detail the dozens of trends

and political, economic or cultural developments that have shaped the EU and its member

states, it is possible to point to some ‘meta-trends’ that have characterised and dened

Europe (and by extension the wider world) over the past decade.

The nancial crash of 2008 – triggered by lending practices in US banks, but with its roots

in debt-driven property market bubbles in many Western nations – quickly enveloped

most of Europe in an economic recession that has not yet passed. While some nations

responded unilaterally to worsening economic conditions by spending large amounts of

public money on propping up nancial institutions, and injected new stocks of money

into the economy through ‘quantitative easing’, the EU as a whole advocated a policy of

‘austerity’ (substantial reductions in government expenditure on public services), which

was mirrored in many of its member states. Nations such as Spain, Ireland and Greece

have experienced huge increases in unemployment and a serious deterioration in the

living standards and livelihoods of many millions of people.

15

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION

The implementation of the EU’s austerity measures has caused signicant disagreements

between member states – in particular Germany and Greece – and played a role in a

process of political fragmentation in some nations, with new political parties emerging on

both the left and the right of the political spectrum. The left-leaning parties (e.g. Podemos

in Spain, Syriza in Greece) have rejected the logic of austerity and called for a return to

higher public spending and employment. The right-leaning parties (e.g. UKIP in the UK, the

Front National in France) have tended to focus on the role of immigration and argued for

tighter controls to protect jobs and services for existing nationals.

These signicant and profound changes to the relative stability enjoyed within most EU

member states previously provide the backdrop against which public attitudes to climate

change, energy, or any other subject must be considered.

The political attention given to the global economic recession, the serious impacts it

has had on European citizens’ lives, and the ongoing challenges that people face in

terms of employment and income are highly likely to detract from the relative perceived

importance of issues like climate change.

Assuming people have a “nite pool of worry” (Weber, 2010), issues which do not

manifest themselves in an immediate and tangible way are likely to be crowded out by

more pressing concerns (Scruggs & Benegal, 2012; Shum, 2012). And there is evidence that

the perceived importance of climate change and environmental issues can drop (even if

temporarily) in response to major economic and societal events (e.g. the recession sparked

in 2008, or immigration ows) both in individual European nations (UK – DECC, 2015) and

across the continent as a whole (Eurobarometer, 2013).

This is the pan-European context against which national attitudes to climate change should

be considered. The paper now discusses in detail the national socio-political contexts in

the four participating nations in the EPCC project.

16

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

Historical, cultural and policy context

≈ The nuclear technocracy

France has the largest share of nuclear electric production in both Europe and the world,

and the second largest number of reactors after the United States. In parallel with military

development in the aftermath of World War II, the exploitation of France’s uranium

reserves in a French-designed electronuclear programme, served a denite goal of

increasing national prestige and energy independence. The 1973-74 worldwide oil crisis

was a springboard for massive expansion of this energy option. France’s national utility,

Electricité de France, sometimes called ‘a state within the state’, grew and prospered; and

historically its nuclear production capacity was generally over demand levels, even with

export schemes. Nuclear power still dominates primary energy production in France and

contributes massively to France’s 50% plus rate of energy independence

4

(CGDD, 2015)

as well as the cheapest electricity in Europe.

5

However, following a national deliberative

exercise, the July 2015 law on ‘Energy Transition for Green Growth’ will reduce the nuclear

share from an average 75% to 50% by the year 2025. In Spring 2016, there was discussion

in the media of the large nancial risks attached to Electricité de France’s Hinkley Point

nuclear new build project in the UK.

The top-down, centralised governance visible in the nuclear sector is very characteristic

of France, as is the idealisation of the scientic elite. Various commentators point to

these traits – exemplied in the nuclear ‘technocracy’ – as shaping public perceptions of

climate change and possible ‘solutions’ to it.

Teräväinen et al. (2011) analysed nuclear discourse in regard to climate change. The major

strategies used by nuclear power advocates in France are necessitation (the authors

quote then-President Sarkozy as saying in 2010 “There is not a single serious person who

could think that we can full our objectives by using only renewable energy sources”) and

naturalisation (as when nuclear power production is described as self-evidently carbon-

free or low-carbon, safe and affordable). The main strategy used by opponents to nuclear

power in France has been scientication, “resorting to scientic evidence and expert

knowledge to refute the argument that nuclear power would help to combat climate

change”, and borrowing government statistics to support claims.

4 A measure of self-sufciency. Dened by the national institute of statistics INSEE.fr as: the ratio between national production of

primary energies (coal, oil, natural gas, nuclear, hydro, renewable energy) and the consumption of primary energy, in a given year.

5 14.12 C€/kWh in 2013, according to Electricity of France. Online: https://www.lenergieenquestions.fr/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/

électricité-comparateur-pays.pdf

France:

A socio-political profile

17

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

≈ Visibility of climate change

The current French President, François Hollande, proposed France as host of the annual

UN climate change summit in Nov-Dec. 2015. This 21st Conference of Parties to the UN

Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP21) was presided by Laurent Fabius, at the

time Minister of Foreign Affairs, with the announced aim of reaching a binding agreement

to limit global warming to 2°C beyond pre-industrial levels. In the lead-up to the meeting,

much Government communication revolved around the need for France to be exemplary

in its environmental performance (the COP21 village severely limited CO

2

emissions

resource consumption) as well as to provide strong leadership to ensure the protection of

the world’s future citizens. Laurent Fabius won high esteem from the assembled delegates,

leading the 195 parties to forge and adopt an agreement called “fair, sustainable, dynamic,

balanced and legally binding”, and “holding the increase in average temperature to well

below 2°C and pursuing efforts to limit this increase to 1.5°C, which would signicantly

reduce the risks and impacts of climate change”.

6

In April 2016, 177 parties signed the

agreement at the United Nations in New York.

7

In 2015-16 many governmental actions included specic references to climate change. For

example, the government-nanced voluntary ‘civic service’ employment programme for

young people (16-25 year olds) incorporated a new topic: ‘Energy transition, climate and

biodiversity’. Climate change is presented as involving every sector of economic life (e.g.

agriculture - for environmental awareness and better use of resources) and all citizens (e.g.

each household will be equipped with a smart electric meter to save energy).

Climate change in France was historically framed as one environmental and ecological

issue among many in the discussion of sustainable development. The term ‘climatic

warming’ (réchauffement climatique) was/is used. Scientists prefer this term putting the

focus on temperature rise, whereas political actors like Laurent Fabius tend to use the term

‘climate disruption’ (dérèglement climatique), placing the accent on the consequences of

global warming (Jouzel, in CNTE, 2015).

Ministerial structures to deal with climate change emerged at least as early as 1992.

In 2005 an Environmental Charter was incorporated into France’s Constitution and

focused attention on the precautionary principle (PP). Although the PP discussion tended

to focus predominantly on present-day public health and safety issues (and scandals),

consequences of climatic change were identied among ‘grave and irreversible’ effects to

be avoided. The growing discussion on the reduction of greenhouse gases has probably

been framed by European targets (cf. the 2008 Climate and Energy Package negotiations;

contrary to most other European countries, France had a limited scope for further

emissions reduction in the power generation sector given her already dominant share of

CO

2

-free power generation, mainly from nuclear; requests by both Chirac and Sarkozy to

consider nuclear power as a renewable energy source or at least a ‘carbon-poor’ source

were rejected by the EC).

6 http://www.cop21.gouv.fr/en/the-french-cop21-presidency-has-presented-a-nal-draft-agreement/

7 http://www.cop21.gouv.fr/en/a-record-over-160-countries-expected-to-sign-the-paris-agreement-in-new-york-on-22-april-2016/

18

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

In France, awareness of climate change has historically been high, but fewer people than

the European average believe that renewable technologies will be widespread by 2050

(Eurobarometer 2011, 2014). While local or regional governments are said to complain

about ‘immature technologies’, the major obstacles to climate adaptation and mitigation

in France’s various regions today were described by one observer to be “administrative

straitjackets, budgetary arbitrage, inability to work as teams, and resistance to change”

(CESE 2015).

≈ Energy production and consumption

France’s energy needs decreased sharply in the hot year of 2014. Primary energy

consumption (adjusted for climate variations) pursued a downward trend seen to have

started in 2005. Final energy consumption reached its lowest level since 1996. Much of the

2014 decrease can be ascribed to the residential sector’s lessened need for winter heating.

Conversely, there was a slight increase for transport, France’s foremost sector of energy

consumption (CGDD, 2015).

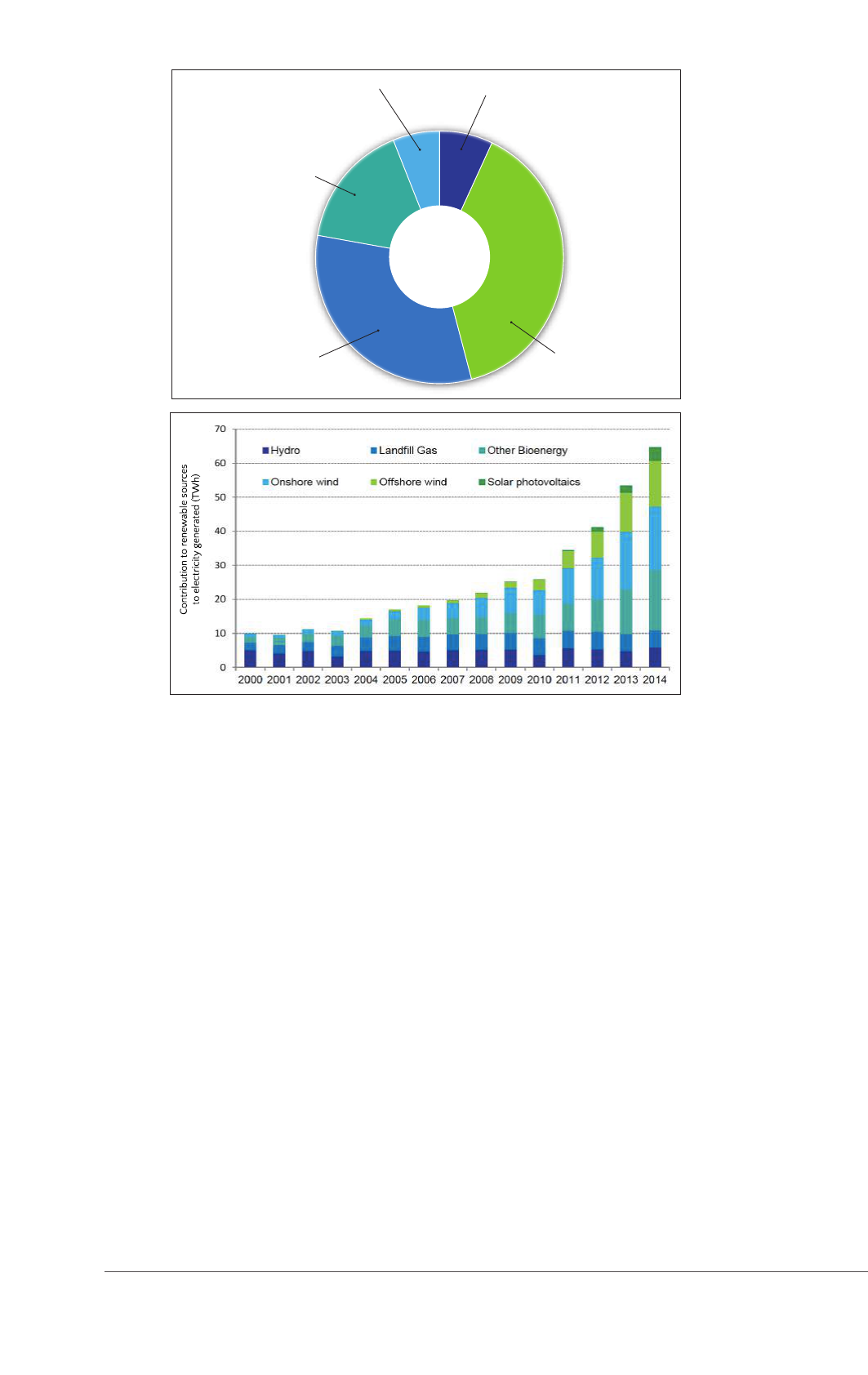

Primary energy production in France for 2014 was composed of 87% electricity, 12%

thermal (renewable fuelwood and recovered waste), 1% oil, and less than 1% each

for natural gas and coal. Within generated electricity, in 2014 nuclear was the source

of 94% whereas hydro, wind and solar power together provided a total of 6%. The

use of renewable fuelwood and hydro were both somewhat lower than usual due to

weather conditions (CGDD, 2015). The 2014 nal consumed energy mix in France was by

descending order: rened oil products (45%); electricity (22%); gas (20%); renewables

and recovered waste fuels (10%); coal (3%). According to provisional calculations, CO

2

emissions related to combustion for energy dropped by 9.4% in 2014 in real terms.

Emissions adjusted for climate variations are clearly falling: they have decreased by 2.4%

per year on average since 2007; their 2014 level was 15.6% lower than that of 1990 (CGDD,

2015).

France is already one of the European countries with lower emissions per unit GDP and

one of the developed countries with lower emissions per capita (7.51 tonnes CO

2

e/capita

in 2012, compared to 9.15 in the UK and 11.47 in the UK, and below the EU-28 average of

8.98 tonnes/capita

8

). This is largely due to the fact that the electricity production is mainly

nuclear.

One interesting question which the EPCC survey will be able to address is whether per

capita emissions relate to the four nations’ public perspectives on climate change and

energy use.

The 2013 update of France’s national climate change adaptation plan (‘PNACC 2011-2015’)

reinforced measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, in particular through improved

energy efciency. Actual implementation was favourably assessed at midterm: 92% of

the planned actions had started; 60% of the needed budget had been engaged (i.e. more

than €100m) in spite of a difcult budgetary context; 60% of actions were progressing

according to plan (CESE, 2014).

8 Eurostat table t2020_rd300

19

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

≈ The Energy Transition law

The programmatic law on ‘Energy Transition for Green Growth’ was adopted on 22 July

2015 after some 3 years of preparation under 4 different ecology ministers, and signicant

debate in France’s two houses of parliament. The law was identied as a agship

endeavour of the Hollande presidency. It is presented as a way for France to ght climatic

impacts, improve adaptation, and provide an example globally. Climate change adaptation

is presented as a growth opportunity (120,000 jobs are expected in the next 5 years to

develop renewable energies). The law legalises the ambitious targets already announced in

the National Climate Plan in 2013:

y 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels);

y 30% reduction in fossil fuel consumption by 2030 (compared to 2012);

y Diversication of electricity production sources to arrive at a 50% nuclear mix by 2025;

y Renewable energies to rise to 32% of nal consumption and 40% of production by 2030;

y 50% reduction in nal energy consumption by 2050 (compared to 2012).

Amongst the measures with a potentially signicant impact on public experience are: state

aids to foster building insulation; clean transport and a circular economy; and support for

better air quality, including trafc restricted zones in cities.

The law was heralded as going far beyond the ‘lowest common denominator’ identied

by the European Council in 2014, and perceived as a good signal in the lead-up to COP21.

However, ecologists criticised the absence of a calendar for phase-in. Discussion on

how to achieve the targeted energy mix was not started until more than six months

after the formal adoption of the law. In parallel to the signature by 177 parties of the

COP21 Paris Agreement in April 2016, Ecology Minister Ségolène Royal issued decrees of

implementation or news of progress on a dozen fronts. These include a call for tender to

develop small-scale, localised hydroelectric generators; decrees on energy performance

requirements for new build and revision of energy standards for existing building stock to

become the most demanding in Europe; etc. Prime Minister Manuel Valls also spoke out on

the need to reform transport policy in harmony with the COP21 agreement.

20

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

Key actors in the French context

≈ Central government

COP21, hosted by France in Nov-Dec 2015, was successfully presided by Laurent Fabius,

Minister of Foreign Affairs (he has since left those posts to preside the Constitutional

Council). The minister was very active in the lead-up to COP21, emphasizing the goal of

facilitating a strong consensual agreement to limit global warming to 2°C, and engaging in

many international discussions.

Climate change and energy issues are dealt with in France principally by the Ministry of

Ecology, Sustainable Development, and Energy (MEDDE). Minister Ségolène Royal has

taken over the presidency of COP21. Within MEDDE, the General Directorate for Energy

and Climate (DGEC) is tasked with inter-ministerial coordination of policy to ght against

climate change, and also to ensure energy supply security at ‘best price conditions’ in an

open market. The National Observatory on Climate Change Effects (ONERC) prepared the

2006 National Climate Adaptation Strategy and the 2011 Adaptation Plan (PNACC) after

a national consultation in 2010. The 2013 PNACC update introduced a methodology to

dene the level of acceptable risk from climate hazards. ONERC acts as the ‘focal point’

coordinating France’s interaction with the IPCC.

Other ministries involved include the Interior, Infrastructure, Research, Agriculture, and

Overseas Territorial Development, etc.

Numerous national agencies give climate change issues a central place in their work

programme, such as ADEME (Energy efciency agency) and BRGM (Geological survey),

amongst others. All promoted COP21 as a signicant rendezvous in which France had

an important responsibility to broker a political solution to climate change. In the Prime

Minister’s ofce, the Centre for Strategic Analysis (now France Stratégie) inquired into

public perceptions of the threat posed by climate change and levels of climate scepticism

(Baecher et al., 2012; CAS, 2012), viewed as a determinants of the negotiating positions

taken by the Parties.

≈ The advisory system

The importance attached by the French state to ecology and sustainable development

issues is evidenced by the multiplication of highly specialised (and often overlapping)

public advisory bodies and agencies from the mid-1990s onward.

The Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE) calls itself the ‘Third Chamber’ of

France in light of its pluralistic and representative character. It counsels Government and the

two houses of parliament on the formulation of public policy. Climate change and energy

transition are strong themes for the CESE. In the lead-up to COP21 the CNTE is preparing

statements and reports, including one analyzing the effects of France’s past 20 years of

climate policy, and another focused on negotiation in view of brokering a Paris climate

agreement. A special emanation, called National Council on Energy Transition (and now

Ecological Transition; CNTE) includes representation from parliament, regional government,

trade unions (both labour and management), NGOs (environment, consumer rights, youth),

chambers of commerce, etc. Starting in 2013, CNTE engaged debate and consultation

events across France to inform and prepare the 2015 programmatic energy law.

21

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

The General Commissariat for the Environment and Sustainable Development (CGEDD)

is tasked with advising Government on issues affecting the environment and climate

change (including construction, transport, urbanisation, use of oceans, etc.). It inspects

the efciency of government strategies and services in these domains and examines

Environmental Impact Assessments for infrastructure plans, programmes and projects.

The Parliamentary Ofce of Assessment of Scientic and Technological Choices (OPECST)

advises the two chambers of the legislature. Studies and hearings are led by members

of parliament with the support of a permanent secretariat and a committee of 15 leading

scientists.

The French Academy of Science is a key advisory body, and is “the only academy

of sciences in the world in which the debate over human responsibility in climatic

disturbance is not yet closed. It is very sad and very grave” (corresponding member and

climatologist E. Guilyardi, in Foucart, 2015). Among its 263 members this historic chamber

contains a small number of active climate sceptics, including geo-chemist Claude Allègre,

a bombastic former minister and author of widely-diffused material on climate change

denial, and geo-magneticist Vincent Courtillot, criticised for repeatedly presenting data

already refuted by peer-reviewed publications. In May 2015, an Academy working group

suspended discussion of a pre-COP21 statement, due to objections over the rule allowing

a minority opinion to be annexed to the majority statement. “It would come down to

publishing a statement that the world is round, accompanied by another stating the

world is at”, said a former Academy president (cf. Foucart, 2015). A new plenary climate

discussion led to the November 2015 publication of a statement conrming the 2010

Academy report viewing anthropogenic climate warming as ‘unambiguous’, recognizing

progress in reduction of uncertainties, and calling for resolute R&D and industrial

innovation to transform the energy system (Académie des Sciences, 2015).

≈ Research institutes

Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace (IPSL) is France’s primary climate research organisation,

recognised among the major world climate science institutions. It is directed by

climatologist and IPCC member Hervé Le Treut, and previously by Jean Jouzel (vice-

president of the IPCC). IPSL is composed of 1400 members including professionals and

students. The CNRS (National centre for scientic research) is the network of university-

based laboratories and research groups. In August 2015, 10% of public information articles

searchable on CNRS’s plain-language website Le Journal contained the word ‘climate’

(43 out of 431 articles). Other pertinent national research institutes are Météo France

(meteorology), IRD (development), and INRA (agronomy). ONERC, mentioned above, is the

focal point coordinating all these institutes’ interaction with the IPCC.

≈ Multi-level governance

France has a dense top-down territorial administrative network including vast

responsibilities in risk governance. This state administration is superimposed upon the

elected government structures (regions, departments, and municipalities large and small).

Most, if not all, administrative and government units include some work programme or

discourse on climate change. Particularly in the run-up to COP21, they are making efforts

to raise awareness and consult the public. The Ecology Minister frequently claims that

22

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

France cannot meet the climate challenge without the local administrations and their

climate mitigation measures. The MEDDE website hosts ‘Wiklimat’,

9

a climate adaptation

knowledge-sharing platform open to all types of public and private actors.

≈ NGOs

Since the 1990s French decision-making has increasingly incorporated stakeholder

representation in advisory bodies and consultations. In particular, two environmental laws

since 2007 have been developed and negotiated through a process known as ‘Grenelle

de l’Environnement’. Themes of debate included inter alia: climate change and energy,

biodiversity and natural resources, environmental health, green development employment

and competitiveness. Stand-out NGOs in France include Greenpeace, WWF, FoE, CARE,

Réseau Action Climat (RAC, a public knowledge network), France Nature Environment,

Fondation Nicolas Hulot (the popular ecologist and action-reporter is also a special COP21

advisor to French President Holland), and other ecological, faith-based or justice-oriented

development organisations.

‘Coalition Climate 21’ is a diversied forum of 75 NGOs and unions (grouping a total of 135

NGOs internationally). It provides a forum where policy differences amongst the different

member organisations can be discussed so as to “contribute to forming a balance of

power favourable to ambitious and fair climate action, and the transformation of all related

public policy”.

10

In April 2015, Prime Minister Manuel Valls recognised their action to inform

and mobilise civil society for a political accord at COP21. The ‘grand national cause’ label

attributed by the PM gave the coalition free airtime on national television and radio.

In April 2016, the television producer and militant ecologist Nicolas Hulot, head of think

tank ‘Foundation for Nature and Man’, emerged in a survey as the most popular political

gure in France.

11

≈ Other actors

Pope Francis’ June 2015 environmental encyclical, partly attributing climate change to

human activity and fossil fuels and calling all religions to take action, was noticed in

the French context. In July 2015, President Hollande received representatives of the

Conference of Religious Leaders of France (CRCF) covering the spectrum of monotheist

and other religions. They advocate climate justice and call for a binding agreement

on climate policy, supporting the 2°C target for limiting global warming. “It is rst and

foremost our relationship with nature, and with God’s gift of creation, that is at stake”.

12

9 http://wiklimat.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/index.php/Wiklimat:Accueil

10 http://coalitionclimat21.org/en

11 http://www.lesechos.fr/politique-societe/politique/021878186464-nicolas-hulot-double-alain-juppe-dans-les-sondages-1217478.php

12 https://www.oikoumene.org/en/press-centre/news/religious-leaders-meet-french-president-to-advocate-for-climate-justice

23

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

≈ Political party positions on energy transition and climate change

In 2009, 78% of French voters stated that the candidates’ environmental platform

inuences their vote (IFOP, in Baecher et al., 2012). Comments below on political party

positions are based on a search of their websites in August 2015 and again in April 2016.

In a representative national survey, ADEME (2014) categorised persons as ‘convinced,

sceptical or hesitant’ about the reality of anthropogenic climate change. Correlations with

declared political afliation or sympathy (with 6 major parties) were calculated. While

signicance was not assessed, sympathisers of the right-wing parties showed the highest

proportion of scepticism in their survey replies. The percentage distributions for four major

parties are reported below. (For comparison, respondents declaring no political afliation

were categorised as 42% ‘convinced’, 11% ‘sceptical’, and 46% ‘hesitant’).

y Socialist party

13

France is governed today by a socialist majority. The new Energy Transition for Green

Growth law, showcased by the Socialist Party as a direct response to the ‘climate threat’

or ‘climate challenge’, is an example of its ‘doctrine of eco-socialism or social ecology’.

Like the government, the Socialist Party highlights energy transition as a great growth

opportunity and a source of hope and optimism. In the lead-up to COP21, the Party

website also laid typical stress on national government’s willingness to involve the local

level and youth. France was urged to show ‘exemplary’ climate behaviour and facilitate

a universal and binding agreement that will ‘maintain global temperature under 2°C [sic]’.

‘There is not an instant to lose, it’s urgent and it’s the responsibility of this generation to

prepare a different world for the coming generation(s).’ France’s role in COP21 was given

a historic, revolutionary dimension: ‘After establishing human rights, we will establish the

rights of Humanity, that is, the right for Earth’s inhabitants to live in a world where the

future is not compromised by the irresponsibility of the present’. In April 2016, the site

focussed primarily on electoral topics but two of three educational video segments on the

homepage presented ‘ecological taxes’ and ‘circular economy’.

ADEME (2014) found that Socialist party sympathisers could be categorised as 51%

‘convinced’ of the reality of climate change, 9% ‘sceptical’, or 39% ‘hesitant’.

y The Republicans

14

The website of the newly named right-wing party centred around former president Nicolas

Sarkozy, and his criticism of the current Socialist government, was searched using the

keywords ‘ecology’, ‘environment’, or ‘climate’. No results were returned.

ADEME (2014) found sympathisers with the UMP (former name of the party) to be 39%

‘convinced’ of climate change, 18% ‘sceptical’, and 43% ‘hesitant’.

13 http://www.parti-socialiste.fr

14 http://www.republicains.fr

24

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

y National Front

15

The far-right nationalist party expresses a populist view on several current climate change

measures. The ‘chaotic and irresponsible’ project, under Sarkozy and then Hollande, of an

eco tax on truck transport is described on the website as a ‘hard blow’ for French truckers

already subjected to ‘intolerable’ disloyal competition from East Europeans. Two FN

parliamentarians published a communiqué on the website stating that they voted against

the Energy Transition for Green Growth law. They recognise climate change affects: ‘health

and climate risks, scarcity of natural resources are growing realities’, but they denounce

the ‘coercive and limiting Socialist ecology’ poised ready to destroy the nuclear sector,

the pride of France. ‘Although ecological issues are global, a pragmatic national response,

respectful of economic and budgetary balances, is needed for a viable and sustainable

ecology.’ In April 2016, ‘ecology’ appeared at the bottom of a list of site keywords, and

returned news items all of which used environmental themes strictly to question the safety

of the French populace and the probity of political leaders outside the Front.

ADEME (2014) found National Front sympathisers to be 33% ‘convinced’ of climate change,

18% ‘sceptical’, and 49% ‘hesitant’.

y Europe Ecologie les Verts

16

The Greens’ website heralds France’s 2015 Energy Transition law, augmenting the share of

renewable in the energy mix, as the concrete outcome of the ‘long battle’ by ecologists,

and welcomes the ‘historic breach’ opened in the ‘most nuclear country in the world’.

A bold picture of progress is painted: “Energy transition is a true societal project turned

towards solutions with a future, enabling job creation (…) and stronger purchasing

power for households”. Still, the ecologists will ‘scrupulously watch over’ the actual

implementation of the law’s measures through decrees of application and interactions

with the upcoming nance law. They denounce large projects on the boards in France

(a new airport, a deep geological repository for radioactive waste) as ‘incoherent and

incompatible’ and completely inadequate for facing the ‘climate challenge’.

ADEME (2014) found Green sympathisers to be 64% ‘convinced’ of climate change, 2%

‘sceptical’, and 34% ‘hesitant’.

15 http://www.frontnational.com

16 http://eelv.fr

25

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

Key climate and energy-related events in France

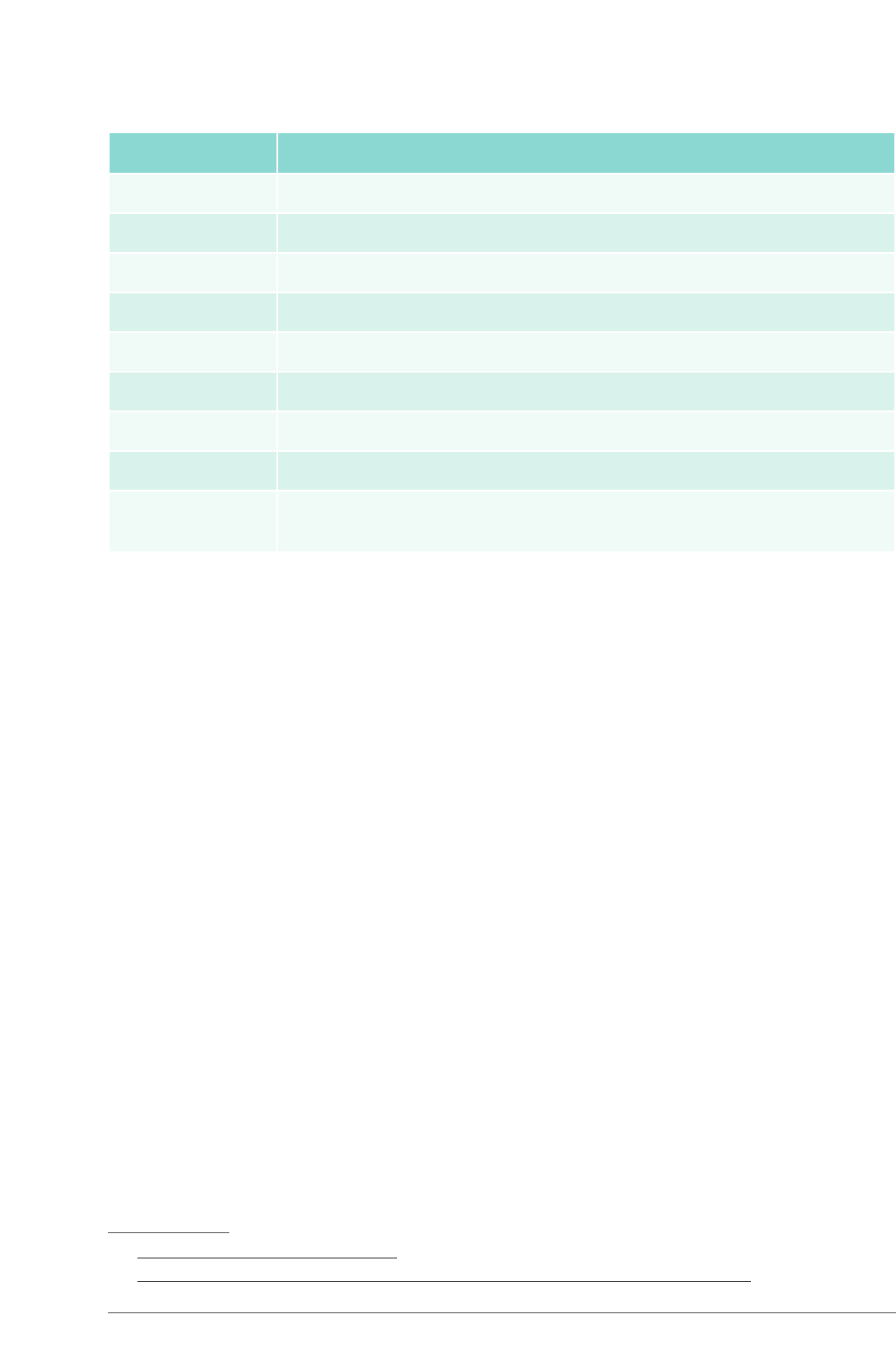

Date Key event

1945 France's nuclear age opens: General De Gaulle secures energy

independence and international prestige for France: a civil nuclear power

programme will ensure energy supply by using (at rst) French-mined

uranium and will produce plutonium for the military programme.L

1974 Plan Messmer: In response to the 1973-74 worldwide energy crisis, which

quadrupled oil prices, Prime Minister Messmer launches an ‘all-nuclear’

energy programme to reinforce France's security of supply. On advice

from the nuclear technocracy, 13 reactors are to be built in 2 years. In

2015 France is the world's proportionally strongest producer of nuclear

electricity and home to the second largest number of working reactors

(58) after the United States.

1986 Chernobyl: The nuclear catastrophe introduced a wedge into the French

public's traditional condence in centralised risk management. Although

the words "the Chernobyl cloud stopped at the French border" may never

have actually been uttered, this remains an iconic statement revealing

France as a paternalistic state in the grips of the nuclear power lobby.

1992 Inundation at Vaison-la-Romaine: A major episode of ash ooding

occurred on September 21 and 22, 1992, in Vaison-la-Romaine, in south-

east France, leading to 47 deaths in 4 localities.

2003

Heatwave: Twenty thousand people died in the French episode of

heatwaves in 2003, during the hottest summer in Europe since 1500.

Unusually high temperatures combined here with socioeconomic

vulnerability and in particular, social attenuation of hazards – a multi-form

inability of individuals and institutions to recognise that people were dying

of the heat (Poumadère et al., 2015). Since then, an efcient prevention

policy has been set up by the French government.

1999 and 2011 The 1999 storms: Lothar and Martin were violent European windstorms

which swept across western and central Europe over 36 hours in

December 1999. The storms caused major damage in France (24 deaths),

as well as in southern Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. 3.4 million

customers in France were left without electricity, one of the greatest

energy disruptions ever experienced by a modern developed country.

The 2011 storm: Xynthia was a violent windstorm which crossed Western

Europe between 27 February and 1 March 2010. At least 51 people were

killed in France, most deaths occurring when a storm surge went over

an ancient sea wall off the Atlantic coast. The storm cut power to over a

million homes in France. Amid turmoil, the French Government announced

in April 2010 the plan to destroy 1,510 houses in the vulnerable areas,

fully compensating homeowners based on pre-storm real estate values.

Xynthia triggered a government policy document called ‘Rapid Inundation

Plan: coastal oods, ash oods and dike failures’.

26

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

2007 Grenelle de l’Environnement: This series of political encounters brought

together government agencies and many NGOs interested in environment

and public policy. Negotiated solutions and agreements were reected in

a Framework Law denitively adopted in 2009.

Among recommendations was to increase the number of high speed trains

(TGV). In 2015, the costly programme was reduced. Typically for France,

political debate led to recommendations somewhat agreeable to all, but

the implementation can be hampered by technical feasibility and cost (as

well as by opposition from specic groups in the general population).

2009 COP15, Copenhagen: Media attention to climate risks was seen to drop

off markedly in France after the failure to reach a political agreement in

Copenhagen (Baecher et al., 2012).

2010, 2011, 2014 Inundations in the Var: A series of ‘catastrophic’ oods in south-east

France destroyed property and took several lives. At blame were

inadequate local zoning plans and uncontrolled residential development.

2010 ‘L'imposture climatique’: A book of scepticism and denial published by

outspoken former Minister of Education and Research, geochemist and

Academy of Sciences member Claude Allègre. Although the publication's

scientic errors, falsehoods and ad-hominem insults were denounced in a

letter signed by 604 researchers, Allègre's position drew attention through

his high prole, his bombastic personality, and the support he received

from a few other public gures (most notably, popular philosopher Luc

Ferry, another right-wing former Minister of Ed. & Research).

2010 Pursuit of Hinkley Point nuclear new build project in the UK: Despite the

resignation in protest by its Financial Director, Electricity of France plunged

forward with its project to build a new nuclear power plant at Hinkley Point

in the UK, with trumpeted support from the Prime Minister of each country.

2011

Fukushima: The tsunami and nuclear catastrophe had a signicant impact

on public perceptions of all types of risks, making it difcult to analyse

annual trends in climate change perception (ADEME, 2011).

2011

Fracking forbidden: With a divided parliamentary vote in June, France

became the rst country to forbid hydraulic fracturing.

2013

Ongoing smart meters: Installation in process, to be extended to 35 million

households.

2012, 2014, 2015 Fessenheim NPP: ‘Fessenheim: To Close, or Not To Close?’ Presidential

candidate Hollande promised in 2012 that France's oldest nuclear power

plant would be phased out by 2016. However, it received €400 million

of funding in 2014 for refurbishment after the post-Fukushima national

safety review, and has been judged safe by the Nuclear Safety Authority.

Parliamentarians say dismantling Fessenheim would be a bad nancial

decision; a strong local/regional lobby points to 1,900 jobs that would be

lost. In March 2015, an incident closed Fessenheim temporarily, renewing

popular fears about its safety. Socialist government announcements

subsequently claimed that the plant will close in 2017 as part of the energy

transition. Greenpeace said there is no reason to focus on the Fessenheim

reactors, “the issue is to close them all, and fast”.

27

European Perceptions of Climate Change • Socio-political proles to inform a cross-national survey in France, Germany, Norway and the UK

FRANCEFRANCE

2015 Grand Carénage (nuclear plant lifetime extension): Of France's 58 reactors,

2 to 8 units will reach 40 years of age each year from 2020 to 2030. If

retired from service, an annual withdrawal from the grid ranging from

1800 to 7200 MWh of electricity would result. In June 2015, the board of

Electricity of France validated the ‘Big Retting’ investment program worth

€55 million over the next ten years. The target is to render 56 of France's

current 58 reactors worthy for continued service up to 50 or 60 years

(subject to authorisation in each case by the Nuclear Safety Authority).

2015 Carbon and Road transport eco taxes: abandon and reprise: These two

taxes were promulgated as part of the Grenelle Law, but withdrawn

because they were seen to be disadvantaging the more modest

economic groups in society (e.g. suburban commuters; truckers and small

businesses in agricultural zones). Outcry from these groups gave a populist

foothold to the opposition. The 2015 cancellation of an international

contract and deconstruction of 173 eco tax toll booths will cost France

some €800 million.

1997, 2015 Air pollution: Air pollution is the number one environmental problem

cited by French residents. The inequitably distributed public health effects

of diesel pollution are recognised by the administration. An extensive air

quality monitoring scheme is in place. Daily air quality ratings and level of

‘ozone air pollution’ are reported through the media. Particularly severe

alerts were given in the summer of 1997 & 2015.

Adopted July 2015 Programmatic Law on Energy Transition for Green Growth: The 3 years

of preparation for the law included consultations and events across

France. It sets ambitious targets in keeping with the government's desire

to show France as ‘exemplary’ in the lead-up to COP21. Transition to

a higher percentage of renewable energies is touted by government

as an opportunity to create 120,000 jobs in 5 years. Despite a start to

implementation, the law is nonetheless criticised by ecologists and NGOs

as lacking a rm plan and calendar.

2015 Successful conclusion of COP21 under French presidency: “Why will 12

December 2015 be remembered as a great day for the planet?”. In an