Foreword

and F.A.Q.

Tools &

materials

An to ni o St ra di va ri

Th e Me ss ia h

17 16

Templates Mould &

blocks

Ribs

a

d

c

Front

4.2

3.6

3.5

2.6

2.8

2.7

3.1

2.6

2.6

2.6

2.5

2.5

3.0

2.9

3.1

Back Neck &

scroll

Assembly Varnishing

Setup Tuning

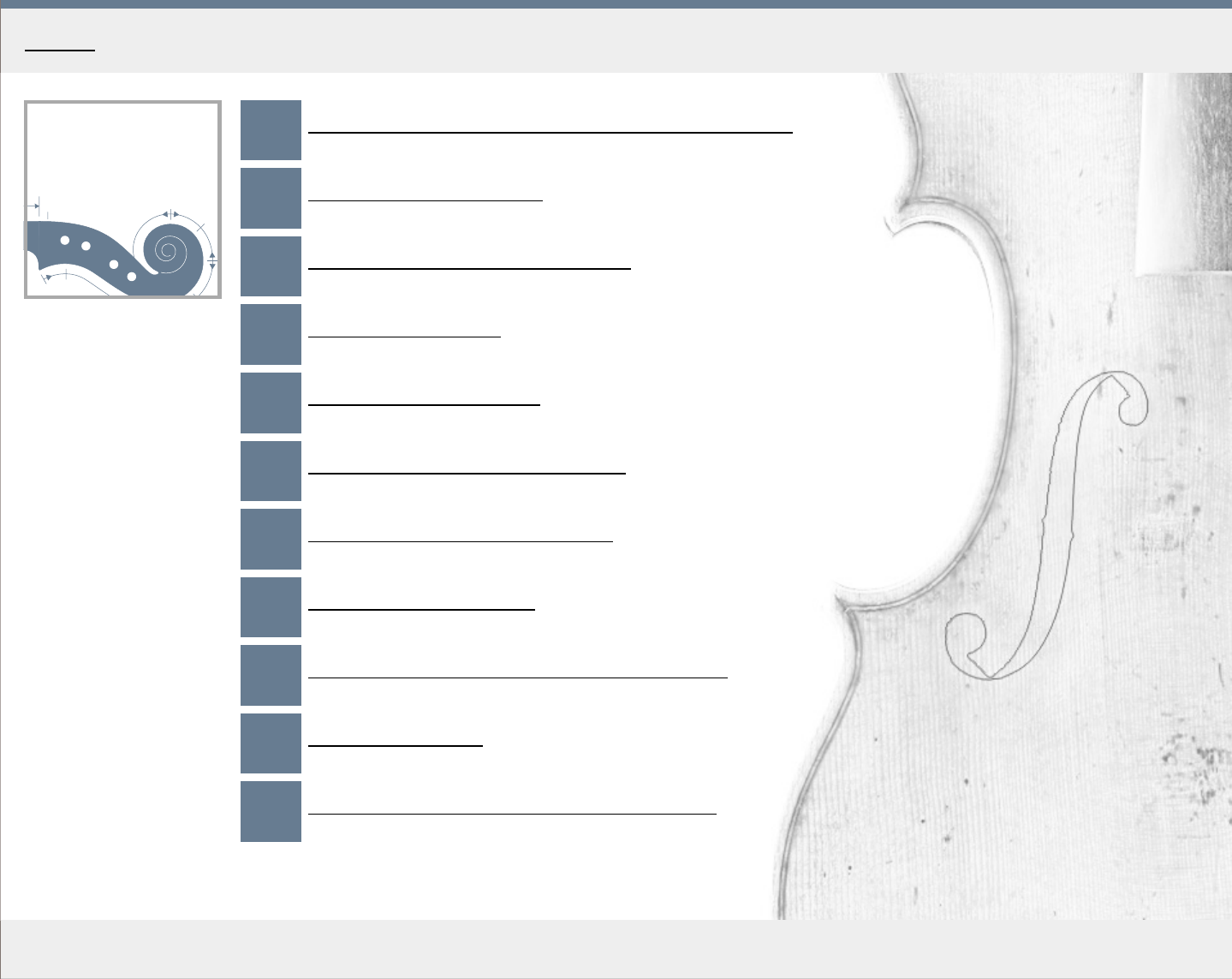

1 2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Measure-

ments

The violin making manual

MakingTheViolin.com

By Vojtěch Blahout, v. 2016

WWW

Forum

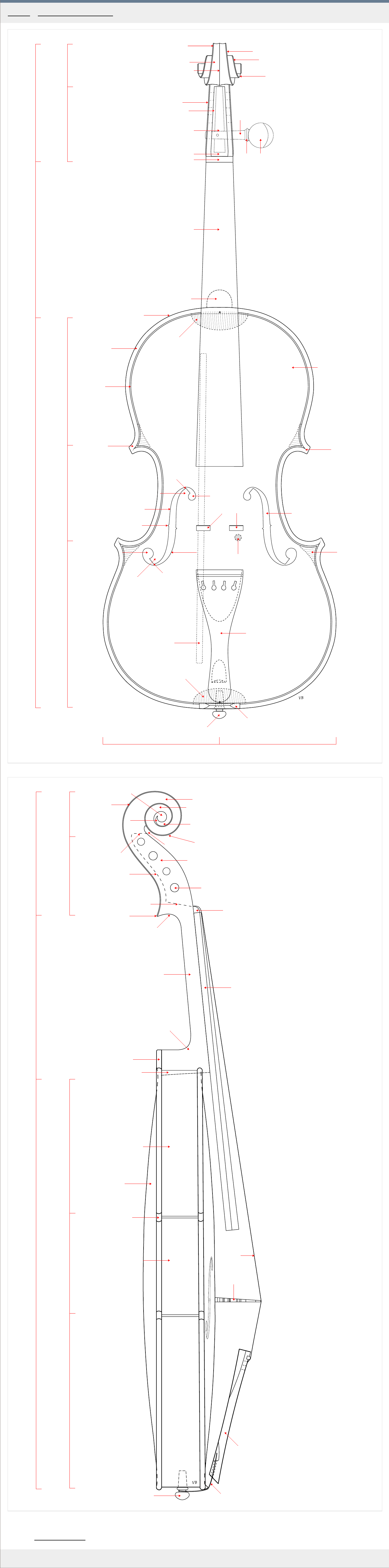

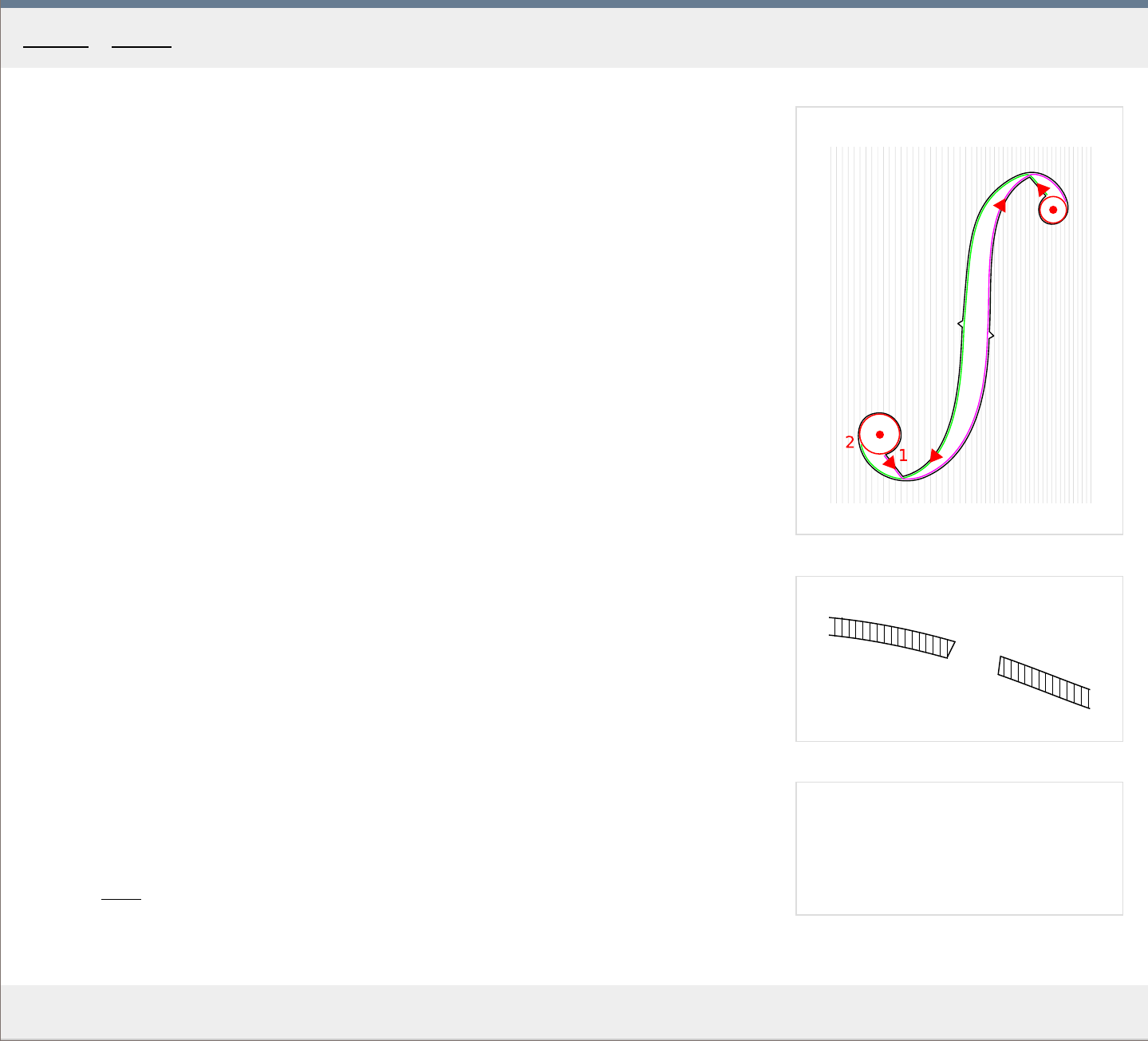

Stradivari Messiah 1716

MakingTheViolin.com

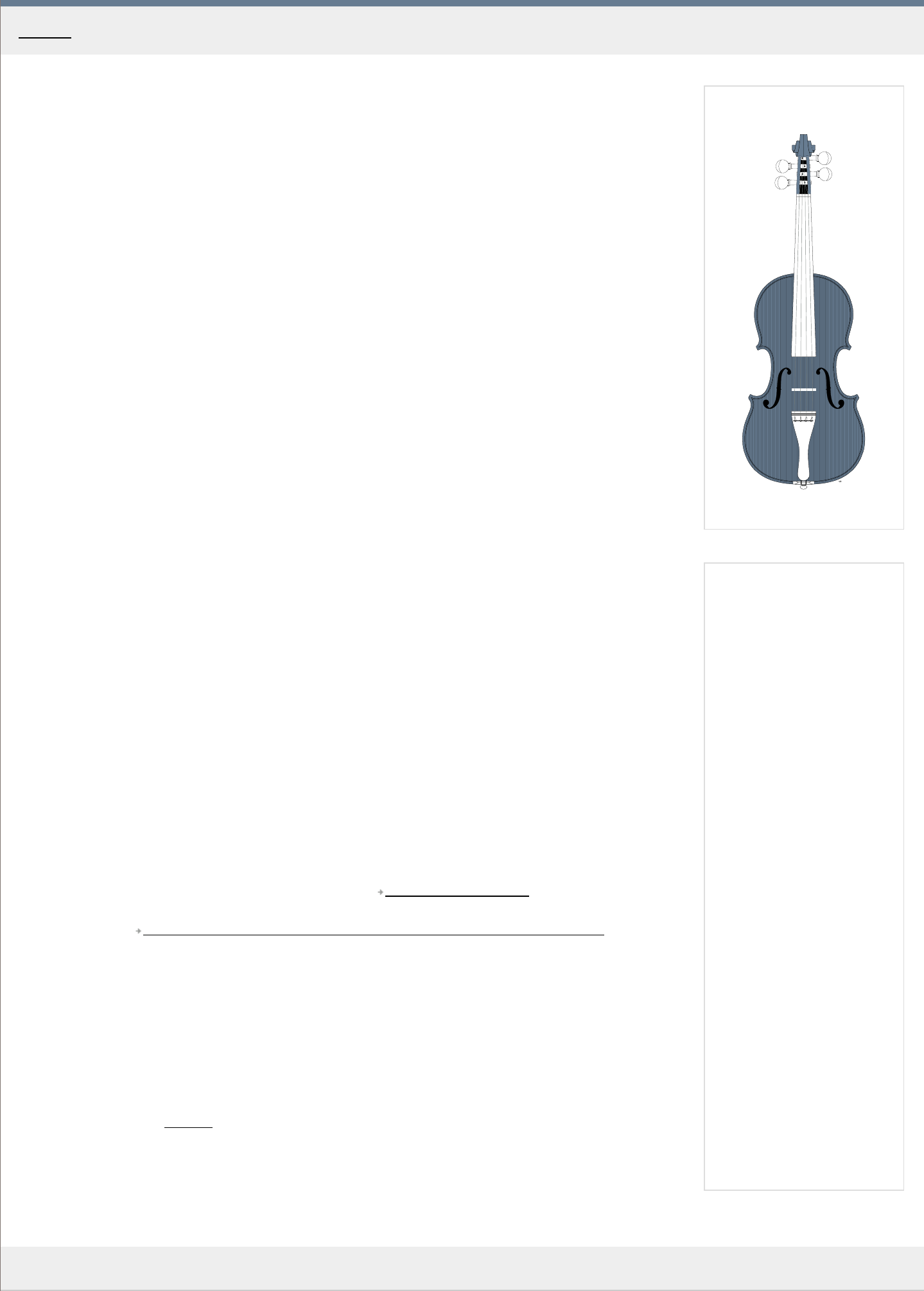

Welcome!

The purpose of this guide is to give basic information about violin making. The aspiring violin maker will

have the opportunity to build an instrument from start to finish with the help of step by step tutorials

accompanied by drawn images.

To make the best of the electronic format, all the images are in vector graphic format SVG, drawn to

exact real world dimensions. At every step of you building experience you can print out the plans and

drawings and use them in direct comparison with what you have at hand. The SVG graphic format is

supported by most modern browsers and editable by the free Inkscape.

My goal was to create a site that would give starting points to those interested in violin making. The

work is by no means complete. There is always room for improvement and I encourage anyone who feel

they might be able to contribute to do so, either by commenting on the pages, or sending their

contributions to me at [email protected]. All additions will be duly credited.

Together, we can make this site a rich, structured information source on violin making.

Enjoy your stay,

Vojtech Blahout

PS: You can now download the whole site as a PDF, see the link "PDF" on the front page.

Frequently ask ed questions

Q> I have a question/I don't understand what you mean by XY . Where do I get an answer?

A> If your question or a comment is about a section of the manual, please feel free to post a comment

on the appr

opriate page or register in the forum and ask your question there. I will try to get back to

you as soon as possible. Or you can always contact me by email [email protected].

Q> I want to edit or add to the content on the website, where is the registration?

A> Due to massive spam attacks, I was forced to close down this option. Please send me an email and

I'll set up an account for you. Commenting, at the bottom of every page, is available without

r

egistration, at least for now.

Q> I want to use the images on this site in my own project, presentation...

A> By all means, use whatever you need, but please consider linking back here or using any other

suitable way to acknowledge the sour

ce. You can edit the images in Inkscape.

Q> I see no images on the right side of the text.

A> If you are having problems viewing the images, click

http://caniuse.com/svg to see whether your

browser is supported. With some browsers, ie. Internet Explorer 6-8 there is the option to install the

Adobe SVG plugin

http://www.adobe.com/devnet/svg/adobe-svg-viewer-download-area.html to

correctly render the images.

Q> I use Internet Explorer and some of the images have wrong aspect ratio.

A>

Please, if you can, use Chrome or Firefox to view the site. I haven't found a reliable method to

display the SVG images acr

oss all browsers. The SVG rendering will hopefully get in line with other

browsers in the next release of the browser. Clicking on the image will display the correct full size

version even in Internet Explorer.

Q> I'm not sure my printer is precise enough to print the plans.

A> Please click on this Test file

and print it out on your printer. Check that the ruler matches yours. If it

doesn't you need to find a way to scale the output, usually in the printer's settings, so that the printout

passes the comparison test.

Home - F oreword

MakingTheViolin.com

1

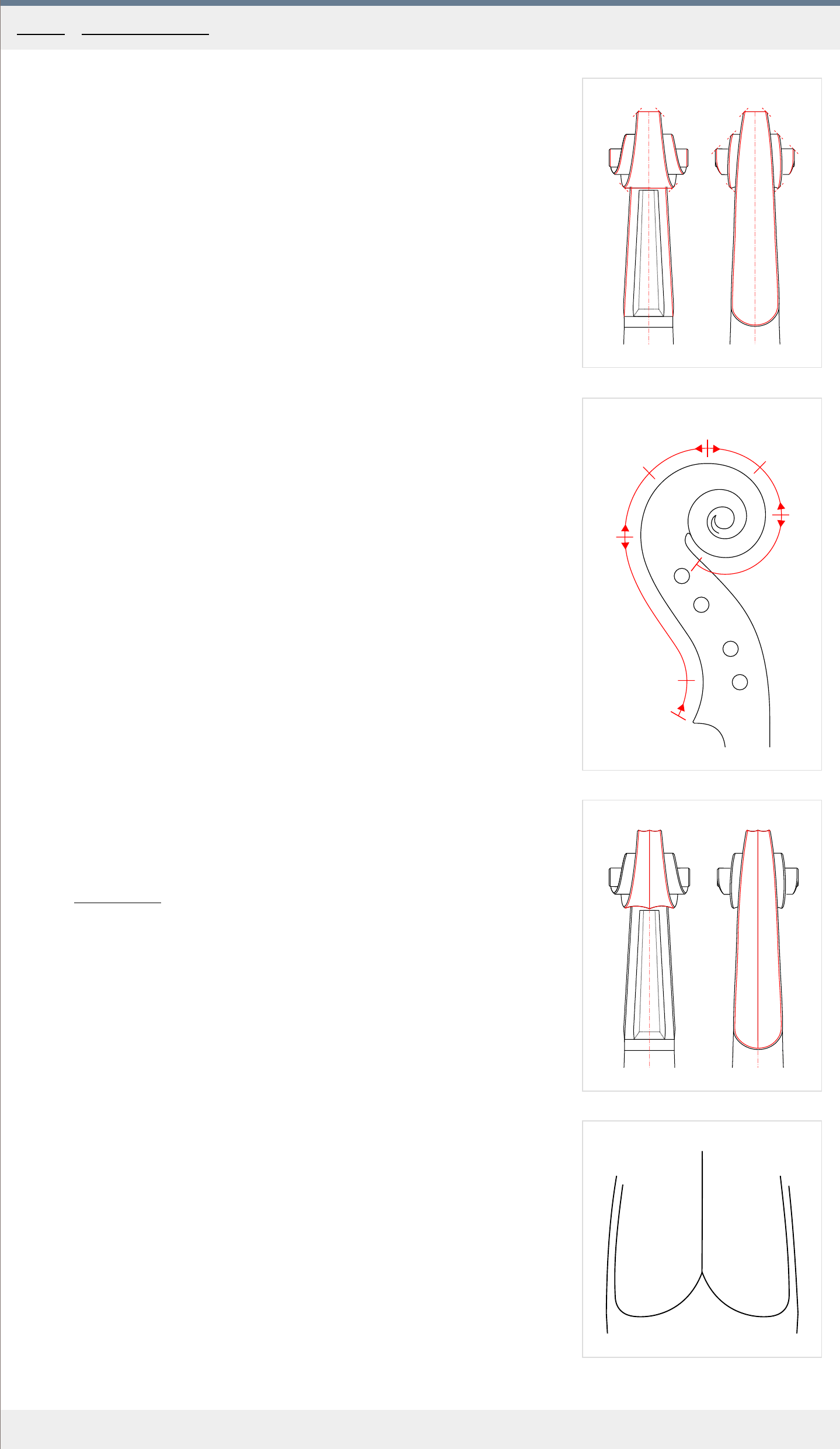

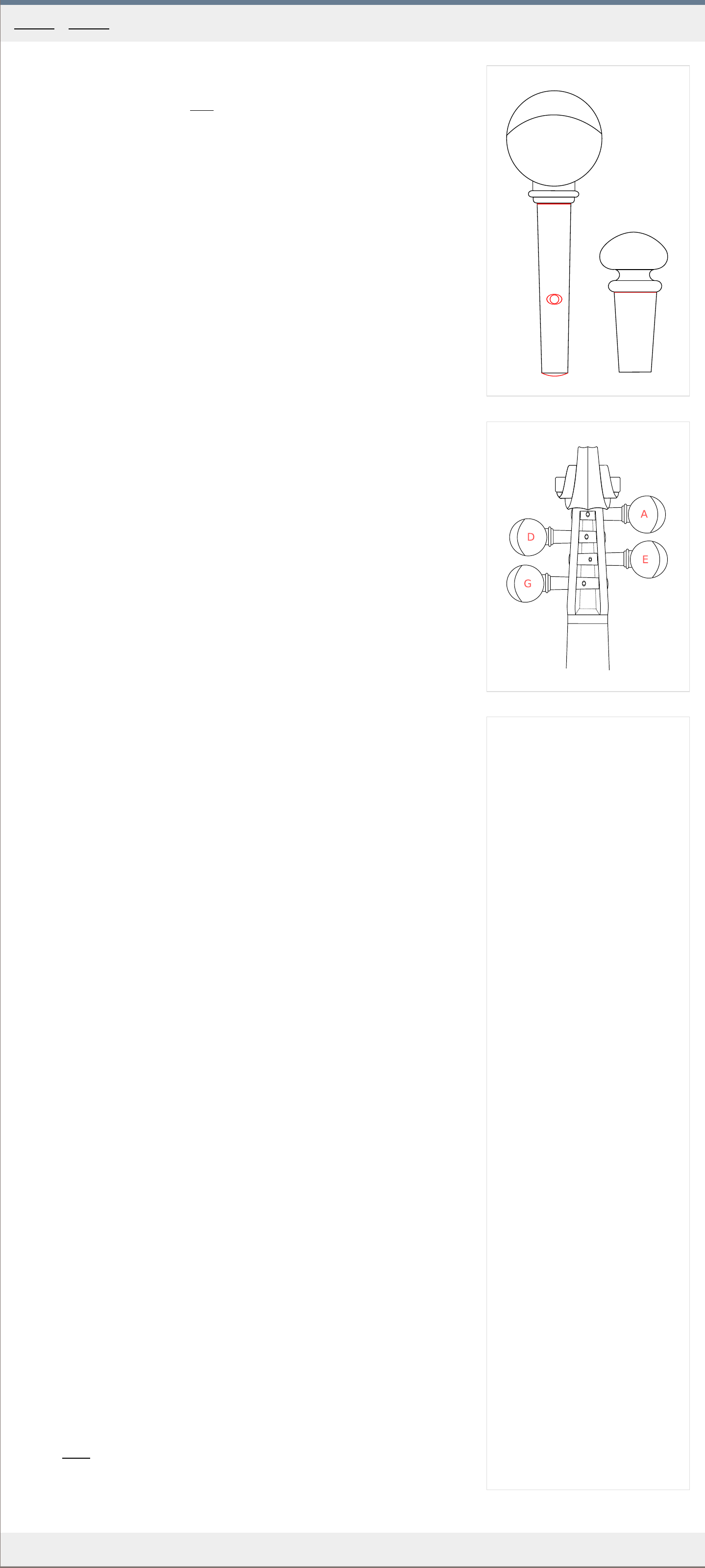

Chamfer

Fluting

Outterwall

I nnerwall

Pegboxfloor

Neckendwa ll

Nut

Centerridge

Firstturn

Secondturn

Finalturn

PegheadCollar

Shaft

Beesting

Corner

Fingerboard

Topblock

Endbutton

Upperwing

Notch

Lowerwing

Lowereye

Bassbar

Tip

Uppereye

Overhang

Purfling

Tip

Stem

Stem

Cornerblock

Bottomblock

Saddle

Topplate

Volute

Pegbox

Upper

bouts

Body

Cbouts

Lower

bouts

Neck

Scroll

Soundpost

Bridgeposition

Fhole

Button

Tailpiece

Shoulder

Bassside Treble side

2

Peghole

Nut

Pegboxwall

Ducktail

Nape

Thr oat

Chin

Fingerboard

Neck

Heel

Button

Backplate

Corner

Ribs

Pegboxf loor

Neckendwall

Voluteendwall

Eye

Firstturn

Secondturn

Finalturn

Comma

Chamfer

Volute

Pegbox

Upper

bouts

Body

Cbouts

Lower

bouts

Neck

Scroll

Endbutton

Cribs

Tailpiece

Tailgut

Bridge

Strings

Neckroot

Category: Tools and materials

Home - Tools and materials - Terminology

1

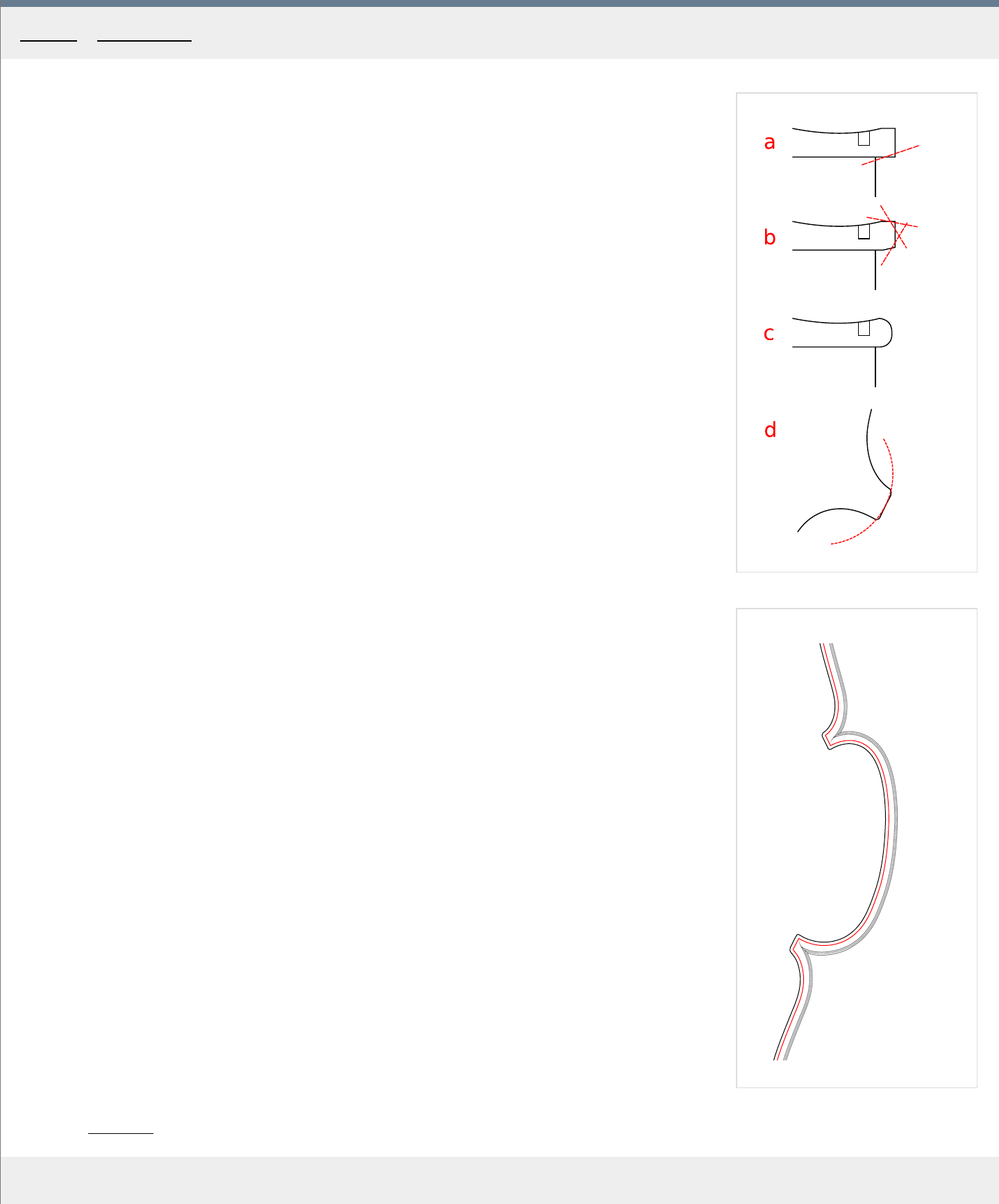

a

b

c

d

2

a

b

3

a

b

4

a

MakingTheViolin.com

When sharpening any instrument, there are two important aspects. You want the edge to be

as keen as possible and you also want it to be the ideal shape.

The sharpening of any tool takes generally two steps: Shaping and/or nick removal and

Honing.

Terminology

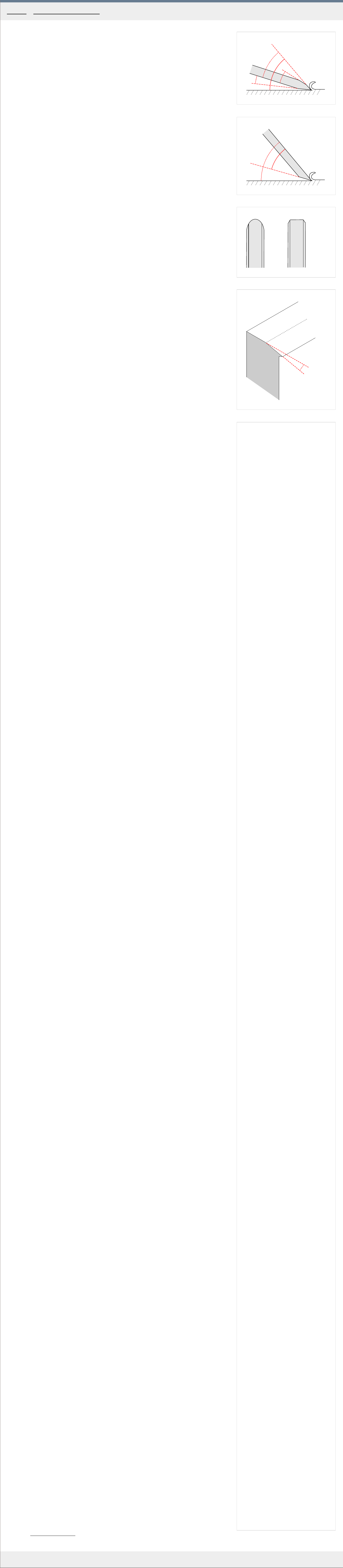

See Fig. 1 for the basic bevel up tool geometry. Bevel up tools include chisels, gouges and

block planes. "a" - Primary bevel angle, "b" - Cutting angle, "c" - Secondary bevel /micro

bevel/, "d" - Back bevel.

See Fig. 2 for the basic bevel down tool geometry. Bevel down tools include smoothing and

jointer planes. "a" - Bevel angle, "b" - Cutting angle.

1. Initial shaping or nick removal

In this step you decide the angle of the bevel. You also remove any nicks and irregularities

making the shape of the tip perfect.

Shaping equipment you need

If you want the bare bones setup, get a bench dual water stone 1000/4000. It should

measure at least 20 x 6 cm. Or even cheaper is a 600 grit sandpaper mounted on a block of

wood.

If you want to go electric, for large mass removals, wet grinders are the best. There is no

need to fear for overheating, but they are rather slow. Sides of the wheel can be used for flat

surfaces. Cheap ones use vitrified stones which are less efficient but degrade more slowly.

When you use your normal dry grinder, overheating is a great risk. When that happens, the

carbon in the steel combines with oxygen leaving you with just soft iron, plus you anneal the

tip making it soft. The whole length where this occurs should always be removed. Also,

quenching tips in water during dry grinding leads to tearing. The tip should be in contact with

the coolant at all times, so don't use dry grinders unless you really know what you're doing.

If you must use a cheap dry grinder, at least change the wheel for something like Norton

38A80 and buy a separate tool rest. If glazing occurs, which can happen when you grind

brass or with cheap grinders a diamond wheel dresser should be used to restore the wheel. It

can also be used to remove any humps on the wheel.

Belt sanders can on many occasions be used instead of bench grinders.

Shaping

The shape and the bevel depend on the metal used but also on the use of the instrument.

Japanese instruments are usually harder 62RC allowing for a keener edge, so a bevel of

higher 45° angle is needed to prevent breaking. With western blades which are a bit softer,

and less prone to chipping, the bevel angle can be less, say 25°.

Cutting the denser sorts of wood requires blunter bevel angles, whereas softer woods allow

for more sharply beveled tips. Ideally, the sharpest bevel should be employed which makes

the tip still strong enough to withstand the pressure of the wood.

2. Honing

During honing you make the bevels smooth as a mirror. Then you create the micro bevel,

making the tip as sharp as possible.

Honing equipment you need

The cheapest tools would be strops, leather or even better wooden. Cut a groove in a

softwood, maybe basswood, apply chromium oxide compound and you have a perfectly

shaped strop for honing. The same for the inner side. In seconds, you can make a wooden

strop that fits perfectly the shape of your gouge.

For chisels and plane irons, if you can, buy a honing guide. It will help you make the bevels

accurate and lead to consistent micro bevels.

An electrified alternative is the use of shaped felt wheels, which are ideal for honing the

inside of gouges. They are a great substitute for the fine bench stones. The to of the wheel

should rotate away from you. Belt sanders are great for honing with leather belts.

Micro bevels

Micro bevels save time, tools and energy. The finest possible edge in the shortest time. If you

need fine angular control, use a honing guide. Only takes half a dozen strokes.

Sharpening tools specifics

Chisels

1

. If new, remove the lacquer.

2. Lap the face so that the edge is not jagged. Make sure the stone is flat.

3. Fix the nicked chisels on your bench stone or wet grinder.

4. Hone.

A chisel should always be at the lowest bevel angle consistent with edge retention. Bevel

angle should be higher for nar

rower chisels, say 30°, to prevent chipping.

Japanese chisels are usually made of hard steel face combined with an iron back which add

toughness and flexibility to the chisel. The chisels are usually very hard 62-RC and therefore

quite brittle. They are usually sharpened at higher bevel angles. Ideal for softwoods. Most of

them are hollow on their face with just a couple of mm of a platform adjacent to the tip, to

ease sharpening.

Planes

With a new plane you will probably need to lap the sole. It is usually hollow. You don't need to

flatten the whole sole, but at the beginning, right before the mouth and at the end the sole

must touch. Use 90 grit on a sheet of glass, iron plate or stone.

True the bed. Put some paint on the iron, insert in position, remove and see there it imprints.

Carbon paper.

Dress the lever cap so that it is in perfect contact with the chip-breaker.

True the chip-breaker. At an angle that makes the point of contact at the very end. Have it set

as close to the keen edge as possible, maybe 1mm, because the closer it is the smaller will

the broken particles be resulting in smoother surface.

Sharpening the iron:

1

. If new, remove the lacquer.

2. Lap the face so that the edge is not jagged. Make sure the stone is flat.

3. Fix the nicked chisels on your bench stone or wet grinder.

4. Bevel down bench planes Stanley no 7, have the usual grind angle of 30-35.

Block planes such as the Stanley low angle 60 1/2 plane can be ground to 20° bevel and

5° back bevel to r

einforce the tip. Make sure the iron sits in the bed perfectly.

5. Hone.

Knives

F

or your knives a bench water stone, double 1000/4000 is alright. The bevels can range

between 10°-30° depending on the steel and application. If you are concerned about the

consistency of your bevels, you can use a spine clamp from you local stationery store. Put

the clamp on the back of your knife to serve as an angular guide.

Honing can be done the cheapest on a leather strap glued do a wooden block, dressed with

chromium oxide.

Gouges

1

. Bevel angle of 15 for soft woods and 25° for hard woods, 30°-35° with a mallet. All around

25°. In or

der to achieve the lowest bevel angle possible and the lowest gouge angle for

the easiest cut, make the outside bevel 15° and the inside 10°. The inside bevel reinforces

the tip and at the same time lowers the gouge angle required for a cut to 15°. This low

attack angle requires less pressure on the gouge and makes your cuts more precise.

2

. You may also decide to change the shape of the tip's end. Square end is good for most

purposes, finger

nail end may be better for the scroll.

3. To hone the gouges, either use a leather belt charged with chromium oxide on an electric

belt sander

. If you prefer manual, go with the wooden strop charged with chromium oxide.

For the inside flute, a shaped felt wheel charged with chromium oxide is good. again going

manual, cut the edge of a scrap wood which reflects the shape of the inside of the gouge

perfectly. Dress with chromium oxide.

Scrapers

A well sharpened scraper should make clean shavings, not dust. In hardness RCs of up to 52

are now available. To create the edge, you need to burnish the scraper. Use a round burnisher

or >RC60. Don't use the backs of you chisels, they most likely are not hard enough. Don't use

screwdrivers as the chromium/nickel coating is thin.

1

. Joint the scraper first to give it a smooth edge at 90° to the sides. A jointing jig can be

used with squar

e scrapers.

2. You can stone the surface, at the side of the bench stone. 1000x

3. Put some nose grease on the burnisher.

4. Clamp the scraper in the vice, and make a couple of strokes parallel to the scrapers edge

with the bur

nisher slightly tilted as in fig. Hold it by the handle with one hand and by the

tip with the other. Move the burnisher in a little to avoid using just one spot on it. In softer

scrapers this will result in a small hook on both sides. With greater angles the scraper will

have to be tilted more to the ground to bite. Use as few passes as possible. Try the

scraper on the wood you intend to use it for.

5

. If you need more hook, run the burnisher at a slight 2°-10° angle to the edge. Do that a

couple of times. Check again.

T

o "pick up" the hook after it has become dull, reburnish again with a few strokes. If that

doesn't help any more remove the hook with the jointing jig, stone and burnish again.

Scraper plane

The scraper plane can be used when thicknessing the ribs. A 45° bevel is usually used. On

top of that, you can create a hook at the end with your burnisher angled at 15°.

Stone truing

After a while every stone will loose its flatness. This may not be a big deal with gouges, but

when sharpening chisels or plane irons, the stone must be reasonably flat. To true your stone,

you can sue a coarse diamond bench stone, silicon/carbide paper on glass or even coarser

stones, which can true your finer one.

Wood cutting tips

When parallel grain cutting, always cut with the grain, that is when the grain is rising up

away from you.

If cutting end grain, always consider the skew cut. It is less demanding of the edge and

lowers the bevel angle further.

When planing keep the mouth just wide enough for the shaving. This also results in smaller

particles, smoother surface. Take thin shavings, they also allow for tighter mouth. Skew the

plane wherever applicable. This applies especially if you have to cut against the grain.

Use a low angle plane, when cutting end grain.

For the cleanest cut with gouges, roll-cut.

Category: Tools and materials

Home - Tools and materials - Sharpening

1

2

20C

40C

60C

80C

100C

3

MakingTheViolin.com

Hide glue and gluing

In the construction of violins only high quality hide glue should be used. Other glues, such as

the white, yellow glue the cabinetmakers use, should be avoided. The main reasons for hide

glue are reversibility /the joint can be taken apart and re-glued again/ and specific toughness

of the joint with no creep and good acoustical properties.

What you need

1

. Some hide glue. It can be in the form of small flakes, pearls or powder. Usually offered are

str

engths varying from 250 to 400 grams. Stronger sorts give you less working times so

take the middle road and buy something of around 300 grams of strength. Usually small

amounts of glue are used during building so you don't have to buy more than 100gr of dry

glue to get you started.

Avoid the hide glue that is offered liquid and premixed.

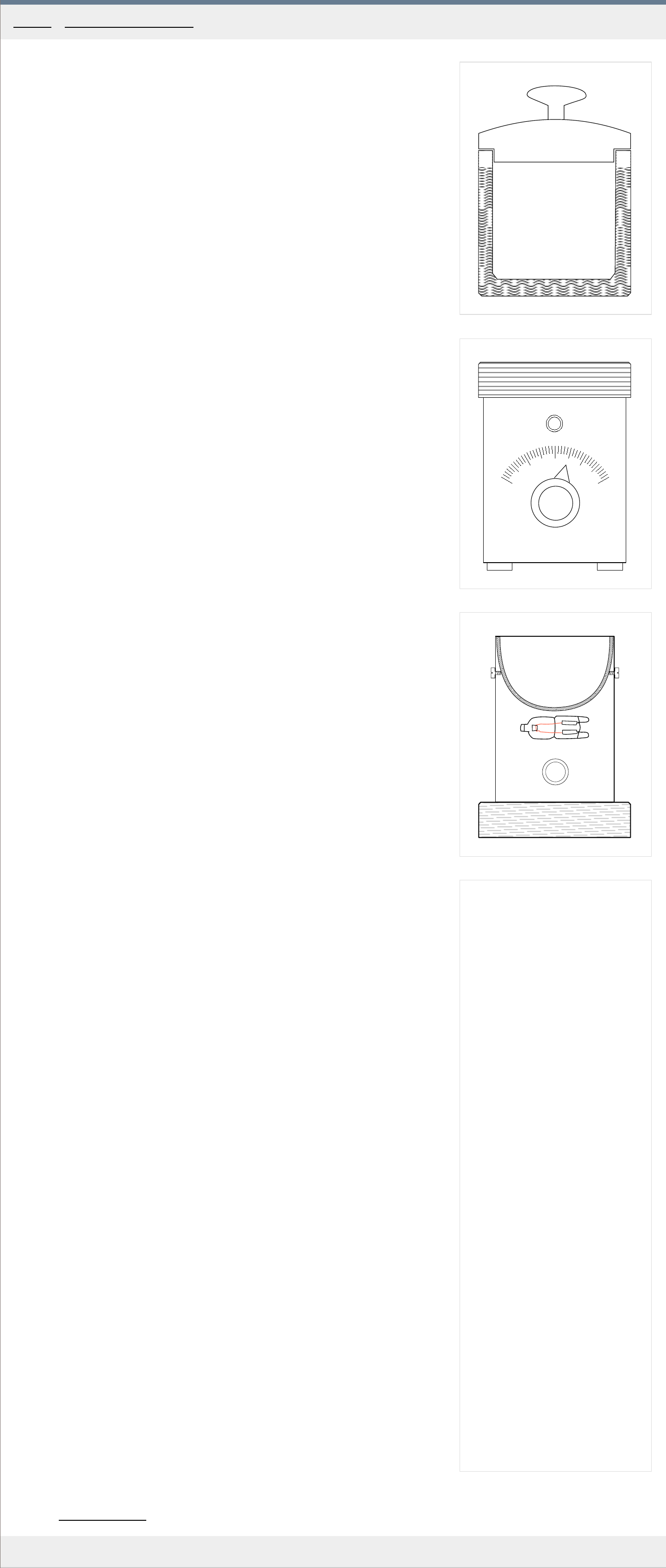

2. A glue pot/kettle. It should be rather small, ideally 8-10 cm in diameter, allowing you to

pr

epare small amounts of glue quickly. Hide glue temperature must never exceed 70C, so

you should be able to regulate the pot's temperature or its power output should be in the

range of 10ths of watts. A regulated, double bottom pot with an insulating water-bed is

perfect. See Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 for an example of the pot and hot plate.

If you are pressed for money, or love to DIY, you can build a small glue pot yourself. It will

work even without the water

-bed, but you must make sure the wattage of the heating

element is not more than 60 watts - a small halogen light bulb, such as the G9, can serve

well here. The upside is that the heat up times are short and you will have a batch of hot

glue ready in a minute. The downside: You will have to watch the pot like a hawk, keep

stirring and turn it off before it overheats. It may seem complicated but when you get

used to this, you can prepare small amounts of glue very quickly. See Fig. 3 for an

e

xample of such a setup.

This glue pot is made of a round wooden base and a sheet of metal turned around a bell,

which serves as a pot. The heating element is the halogen light bulb mentioned above.

Use your imagination.

The bottom line: You don't need anything fancy or regulated but a good thermometer

befor

e you get the feel for this is a must.

3. A set of brushes and knives. One smaller 5 mm wide all-purpose brush, one larger 20 mm

wide for bigger jobs. A palette knife will be used to work the glue into the seams when

gluing to top and bottom plates to the ribs.

Preparing the glue

1

. For a start, put a teaspoon of hide glue in the glue pot and add about 100ml of fresh

water

.

2. Stir and let stand for 1-2 hours. When you see the glue has gelled and grown in size

considerably, it is time to heat it up.

3. Turn on the glue pot and make sure the temperature never exceeds 70C for longer periods

of time. Should your hide glue start to boil, don't use it, and prepar

e another batch.

4. Keep stiring until you are sure there are no undissolved pieces in the pot.

5. Check for the thickness of the glue. Visually, the glue is hot and thick enough if a film

starts to for

m over its surface. You will learn to guess the right thickness by letting the

glue drop from the brush. The medium thickness hide glue should feel oily between your

fingers. The thin hide glue used for glue sizing should almost be the consistency of milk.

Make sure the glue is about 70C when testing for thickness.

Application

1

. Always try to work in a warm room with no droughts so that you have more time to make

the joint.

2. Preheat the critical joints with a hair dryer, ie. center seam joints.

3. Make sure everything fits right without the glue first.

4. Have everything to hand, you need to act quickly and precisely.

5. Don't use more glue than necessary and always remove the surplus with a damp brush or

towel. Sometimes it may be better to wait for the glue to gel a bit for easier removal. Be

especially car

eful with the areas that will be varnished. Areas with hide glue blotches will

not absorb the stain properly, leaving marks.

6. When you are using the palette knife, always have it preheated in hot water, otherwise

the glue gels fast when in contact with the cold knife.

Drying times

Under nor

mal humidity and temperature the hide glue should be left to dry for about 12-24

hours. Usually overnight should be enough time. More structurally important joints, such as

the center joint or the neck joint, should be left undisturbed for the full 24 hours.

Hide glue shelf life

The dry hide glue should be stored somewhere... dry. Properly stored, it has an almost infinite

shelf life.

The shelf life of the prepared hide glue depends on many factors: humidity, room

temperature, possible contamination, thickness. It all boils down to how bacteria friendly

your workshop is. The freshly prepared glue is the strongest, so for critical joints, ie. when

joining the billets for the top and bottom plates, I would always use fresh glue. On the other

hand, many violin makers may leave their glue in the pot for days without apparent loss of

strength.

Some people prepare the glue, let it cool down, cut it up into small cubes and put them in a

fridge.

The signs of bacterial degradation are the change in color, often turning brown, tiny watery

pits on the surface and a bad smell.

So if you want to stay on the safe side, always prepare a fresh batch of your glue.

Category: Tools and materials

Home - Tools and materials - Glues

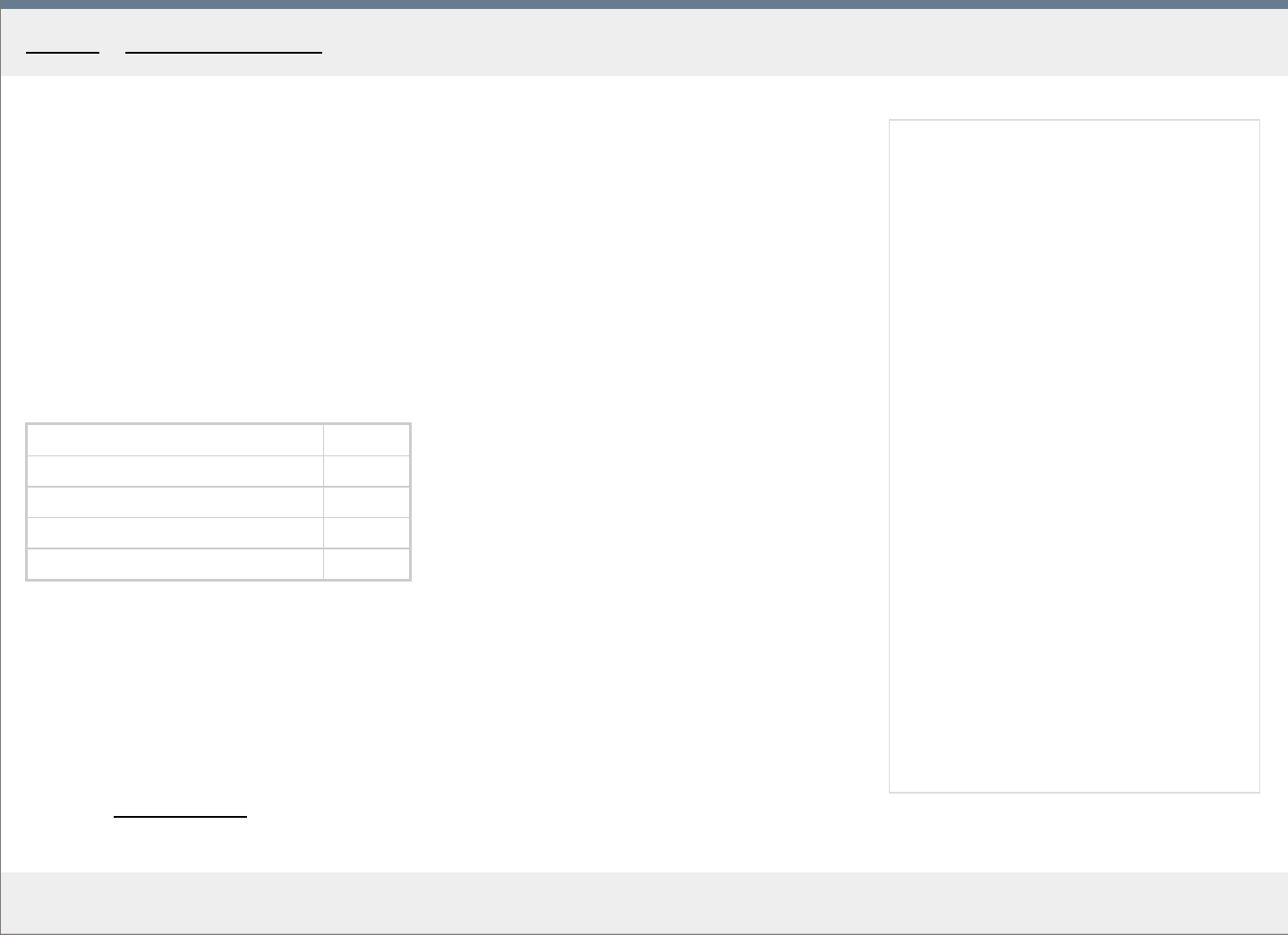

A method of ascertaining the specific gravity of wood is to submerge the wooden billet in water

and divide the length of the submerged part by the total length of the billet.

Alternatively, you can use the widget below to calculate the specific gravity for you. Be sure to

measure the dimensions and weight as precisely as possible. Typical results range from 0.38 - 0.45

for spruce and 0.50 - 0.60 for maple.

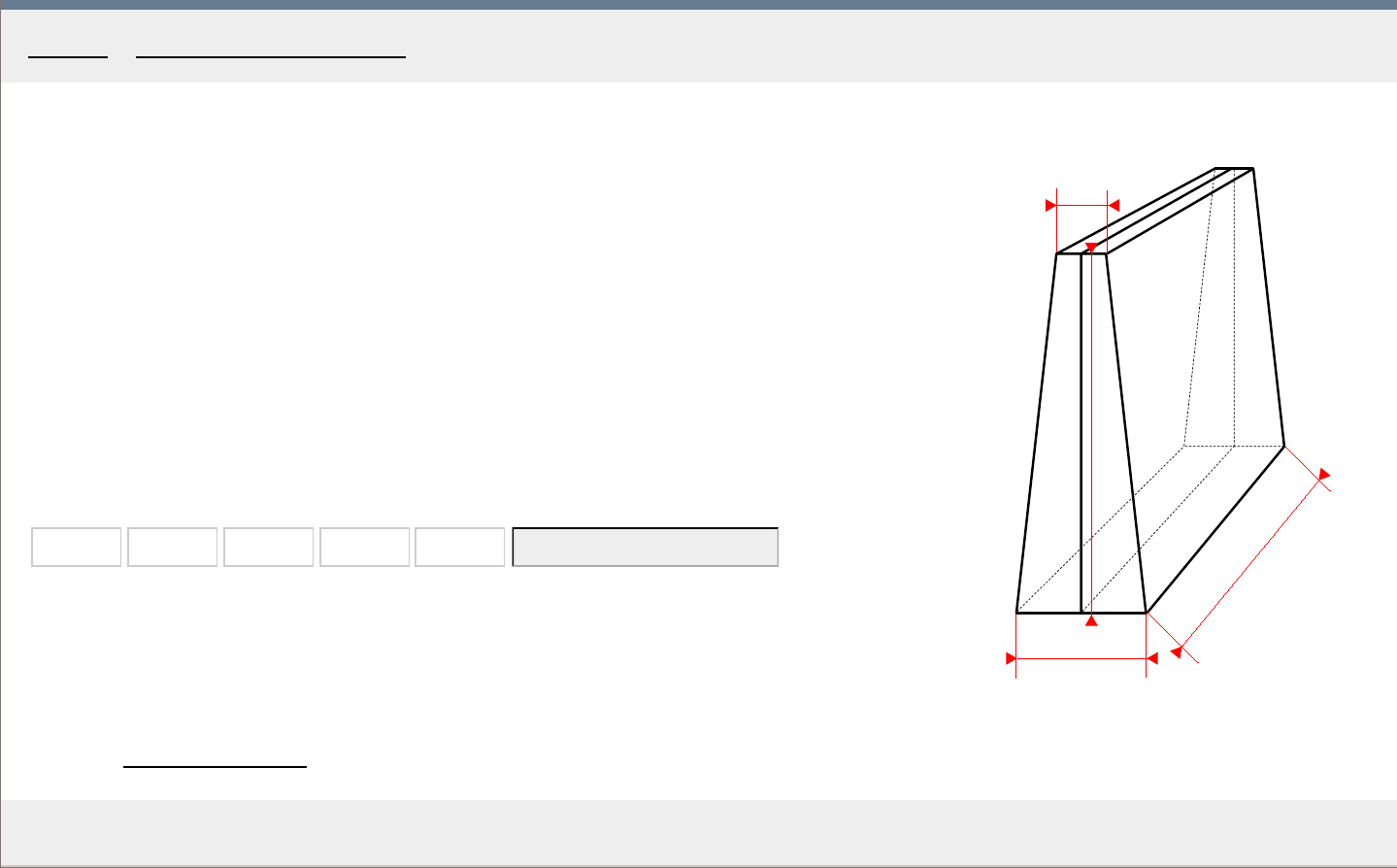

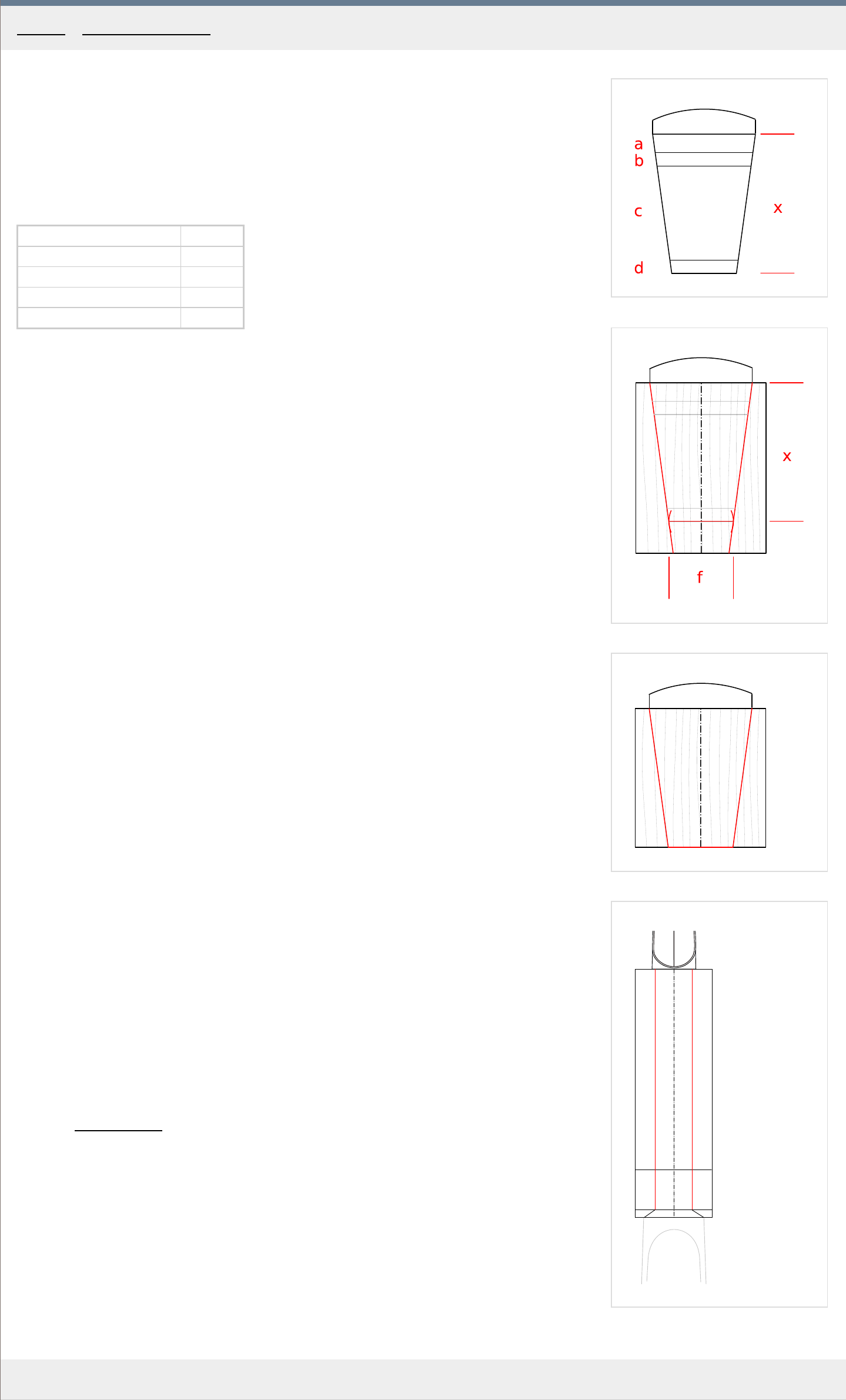

The dimensions are input in millimeters , the weight in grams . The widget first calculates the

surface = ((a+c)/2)*b, then the volume = ((surface +surface )/2)*d and finally specific gravity

= weight /volume .

a b c d Weight

Calculatespecificgravity

a

b

c

d

MakingTheViolin.com

Determining the specific gravity of wood

Category: Tools and materials

Home - Tools and materials - Specific gravity calculator

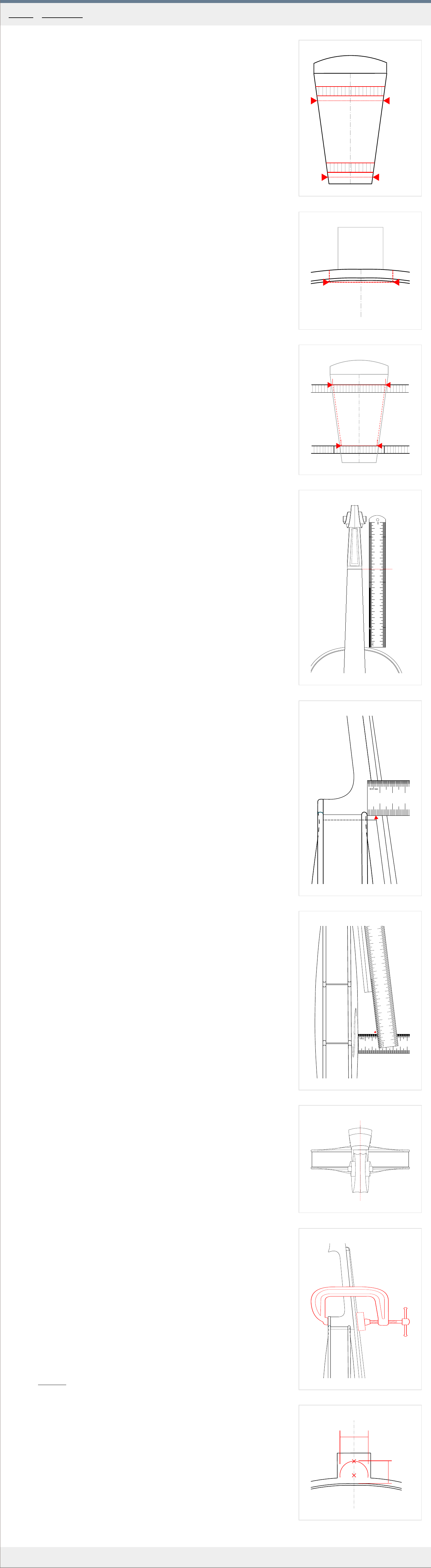

1

2

B

C

A

3

X1

X2

4

MakingTheViolin.com

A few thoughts

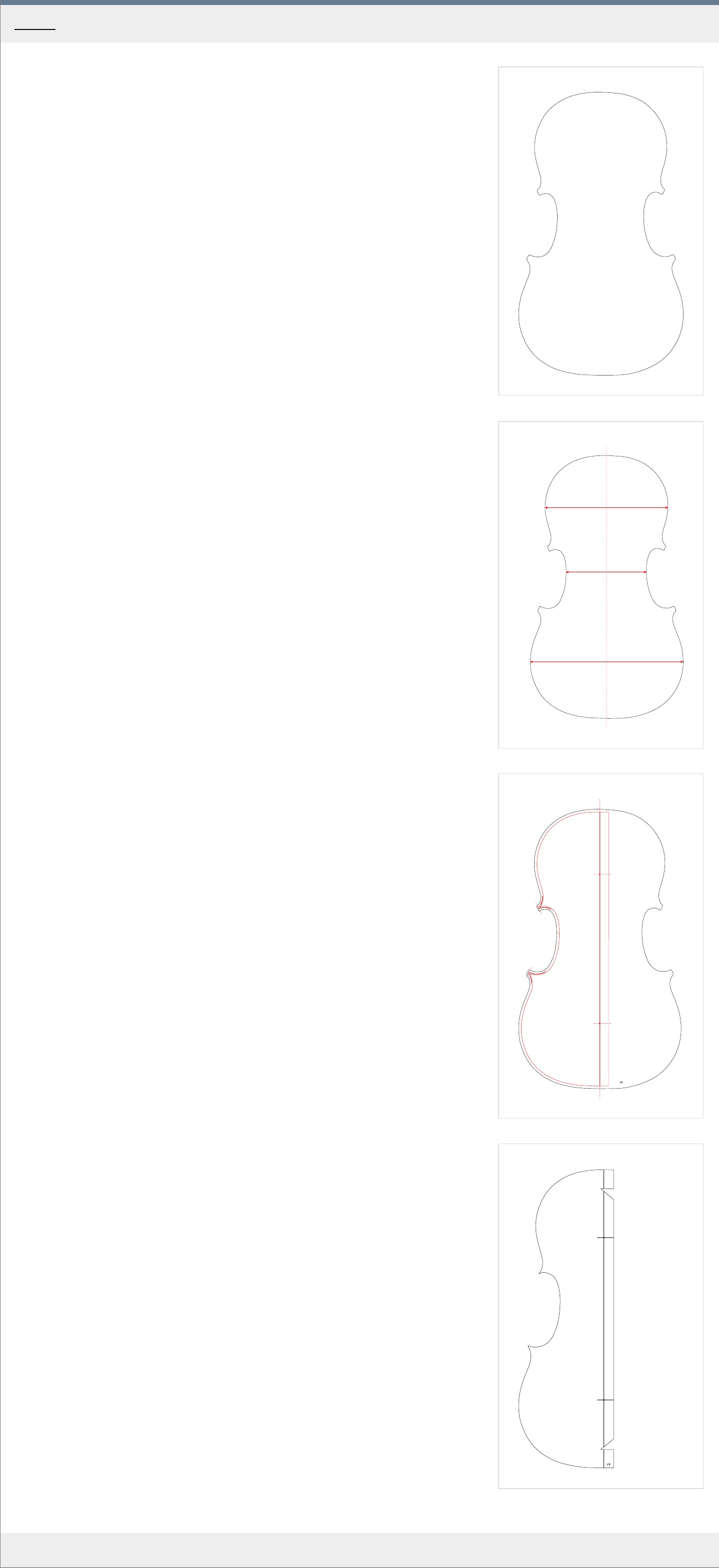

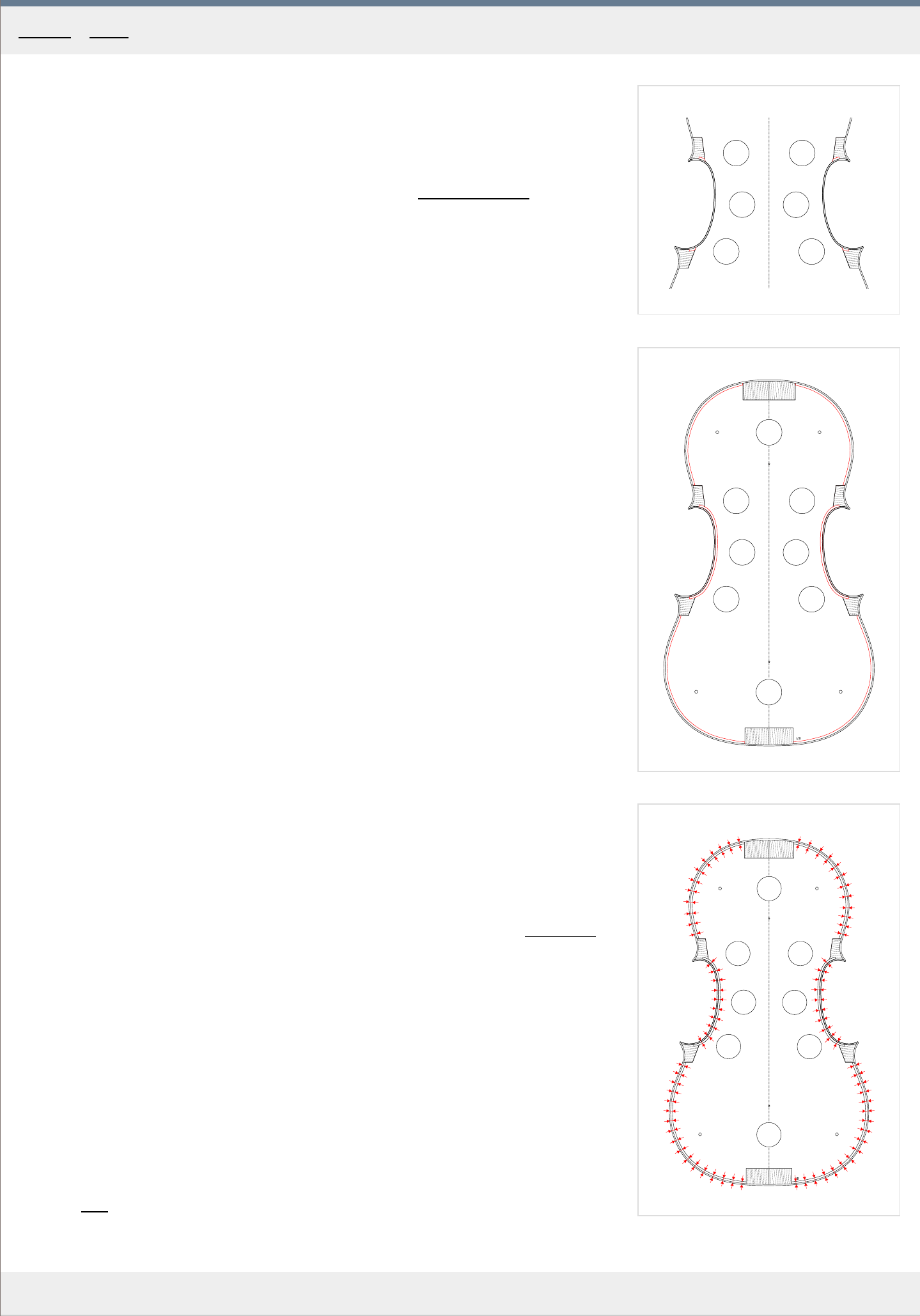

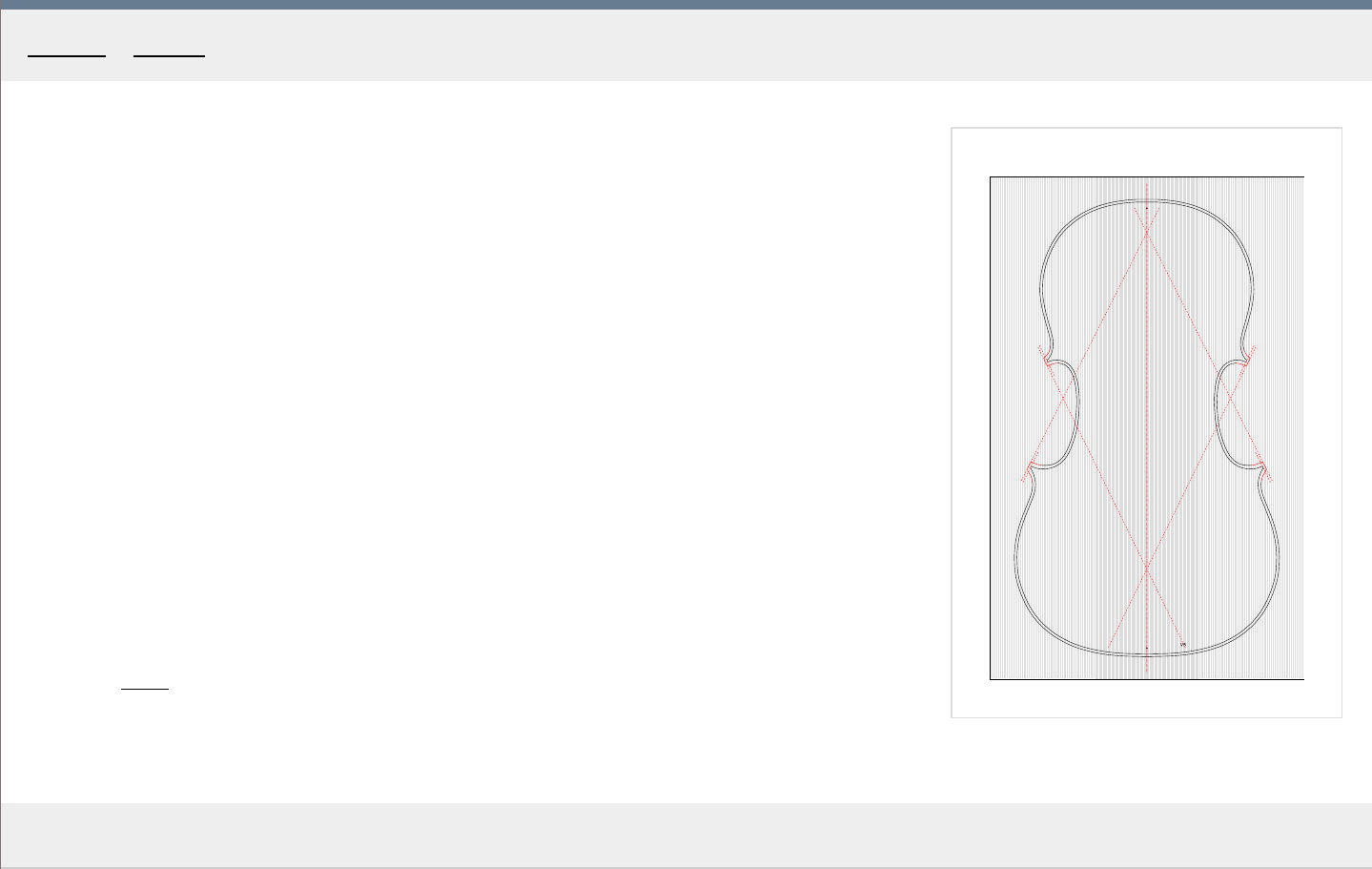

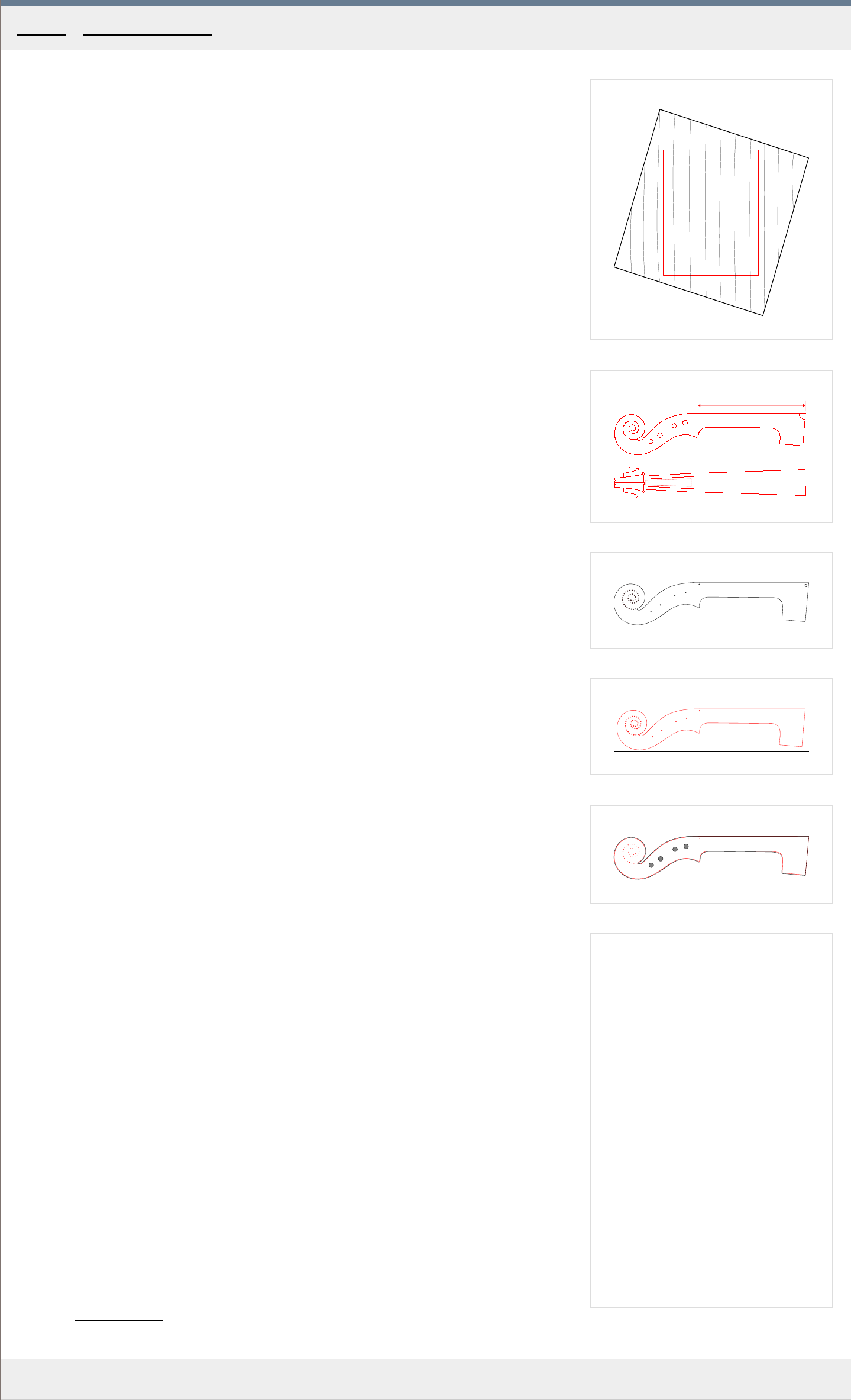

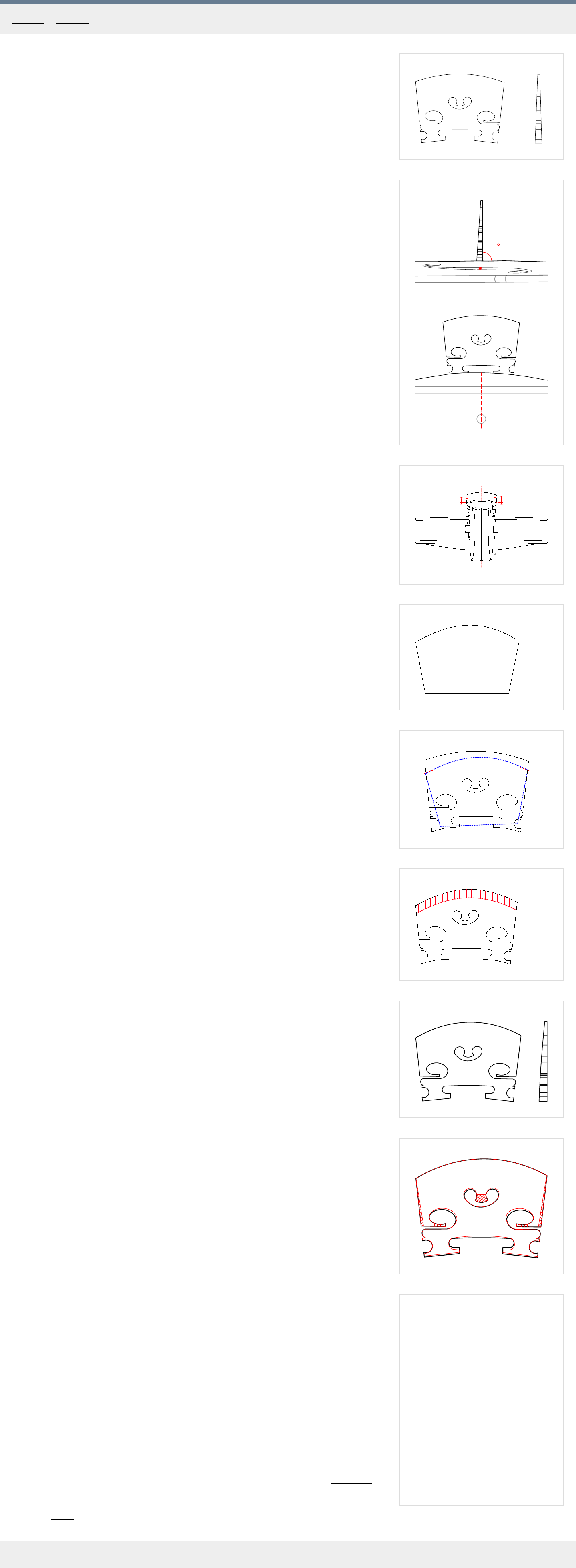

The template is the basis of all your work on the violin, so a lot of effort should go into its

proper execution. You have to decide whether you are building an exact copy of an existing

instrument or an approximated interpretation of an existing instrument or an original

construction.

In case of an exact copy, you will use a full size template describing the outline of the copied

instrument to the greatest detail. If this instrument is of any considerable age and has been

used, it will have at least some wear. That wear will get copied as well. The shape of the

instrument itself changes over time, the wood shrinks differently in various directions. All that

gets copied. Choosing this approach, if you want to arrive at something "right" you have to

work very precisely, because you are at least 8 "generations" away from the original outline

and every generation brings some amount of error with it.

In case of an interpretation, you can still use a full size template, which you will "correct" to

some degree. You can remove obvious spots on the outline, where the wear has caused the

shape to deteriorate and you can also correct some of the asymmetry.

Besides the full size template, you can use a half template, which you flip on the other side to

get perfect symmetry. The downside of this is that you will have to choose which half of the

original violin you will use. Without correction, if the original violin is very asymmetrical you

will end up with a very differently shaped violin. To illustrate this, get a picture of someone`s

face, and use just the left or right half to reconstruct the whole. The change may be quite

dramatic.

Knowing all that, for a novice, who is very likely to introduce a lot of errors, the symmetrical

template is almost always a better choice. Remember, errors tend to accumulate with

iterations.

You may also decide that you want to construct the outline yourself, without it being directly

based on any existing violin. There are many systems of violin construction out there but to

me the most simple ones, based on the use of compass and basic geometry seem the most

plausible. For an in depth approach to this, see the great François Denis` book Traité de

lutherie.

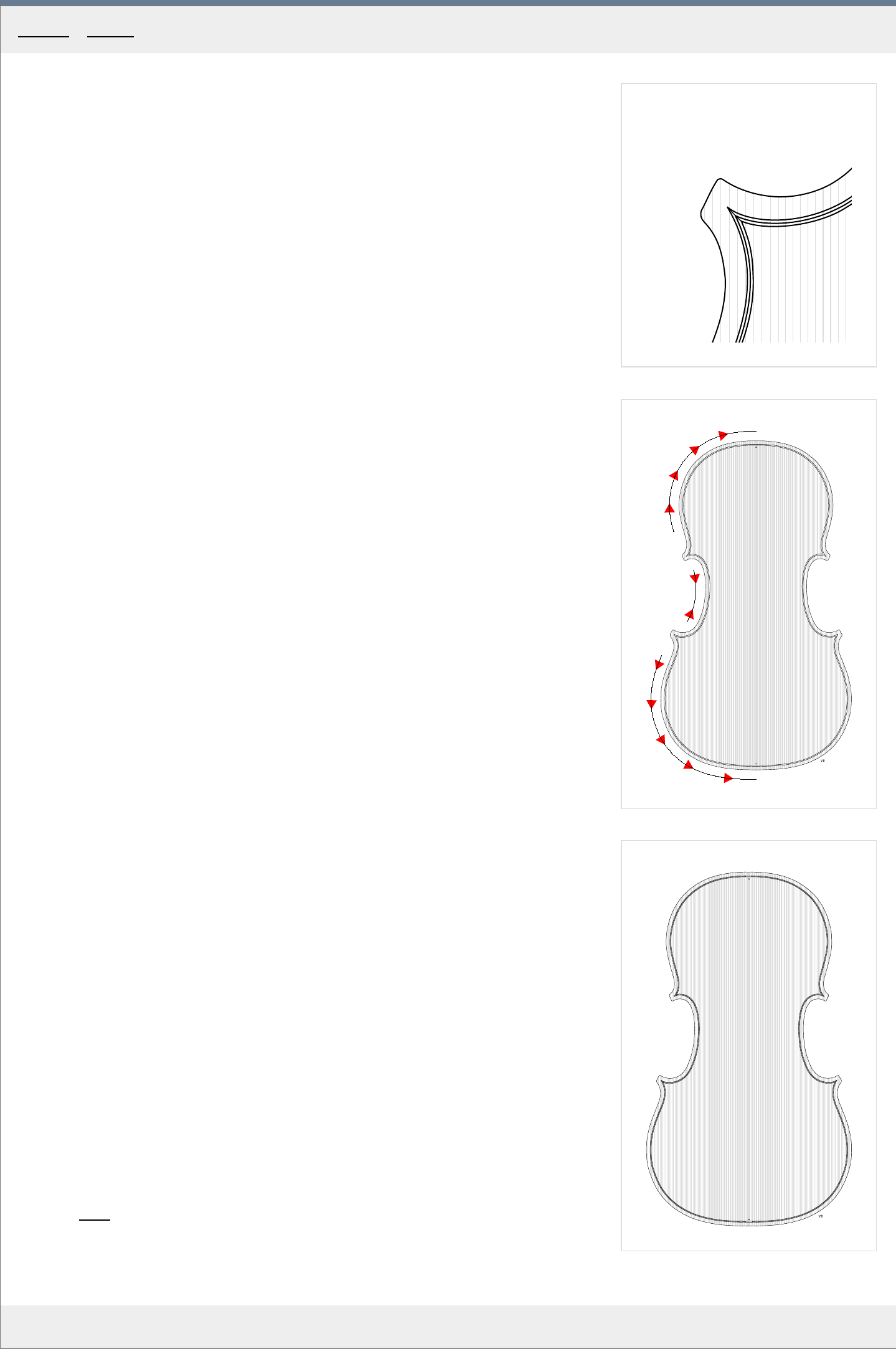

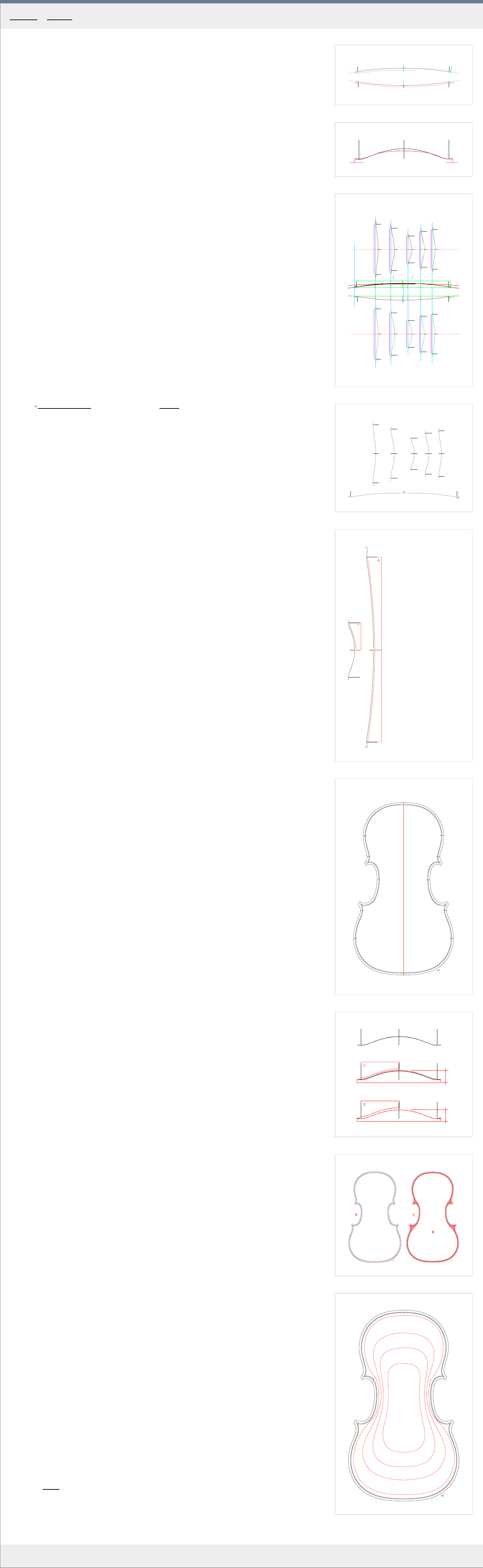

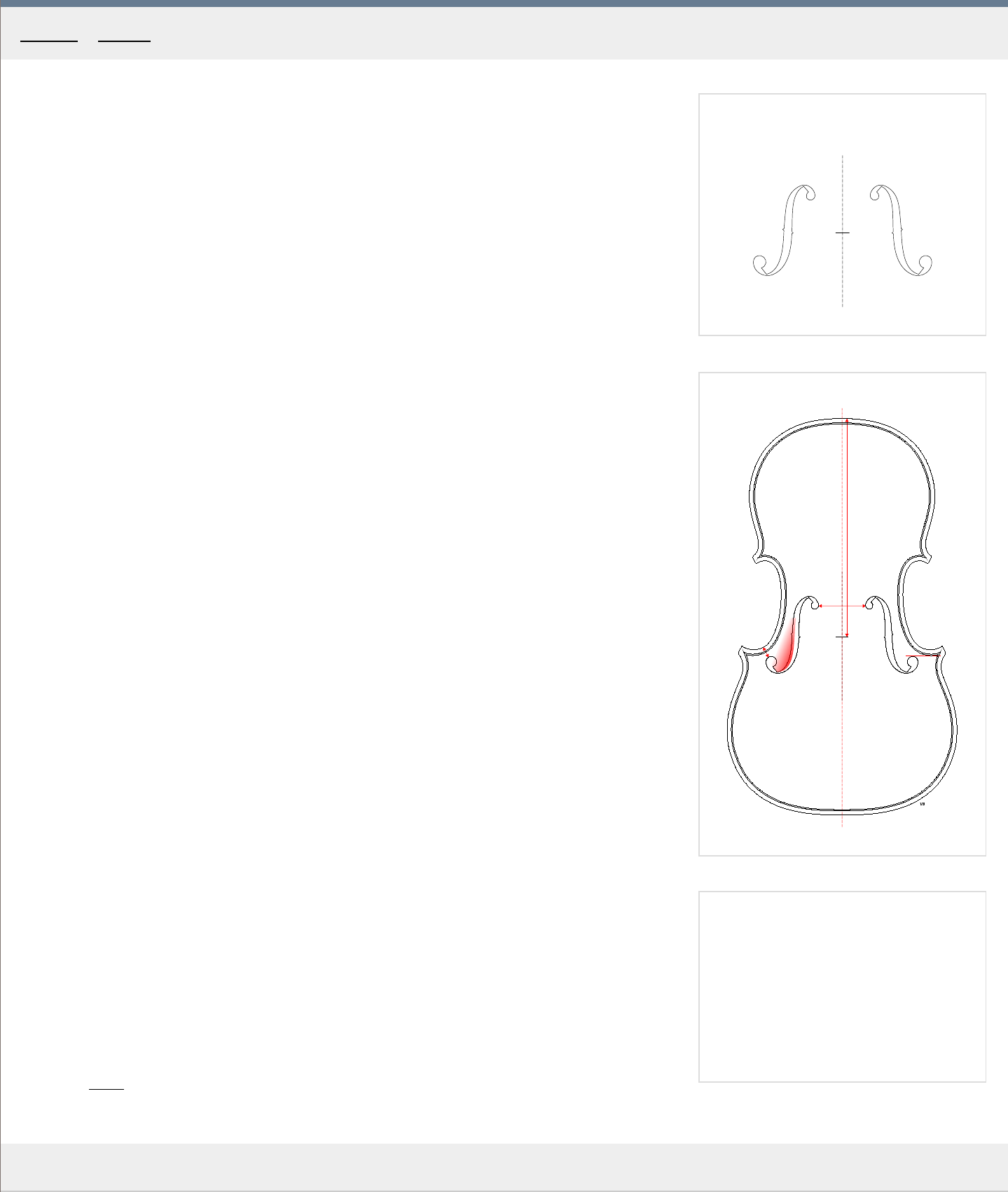

Because this manual is meant mainly for beginners, we will take the full outline and convert it

into a half template from which in the next chapter we will construct a perfectly symmetrical

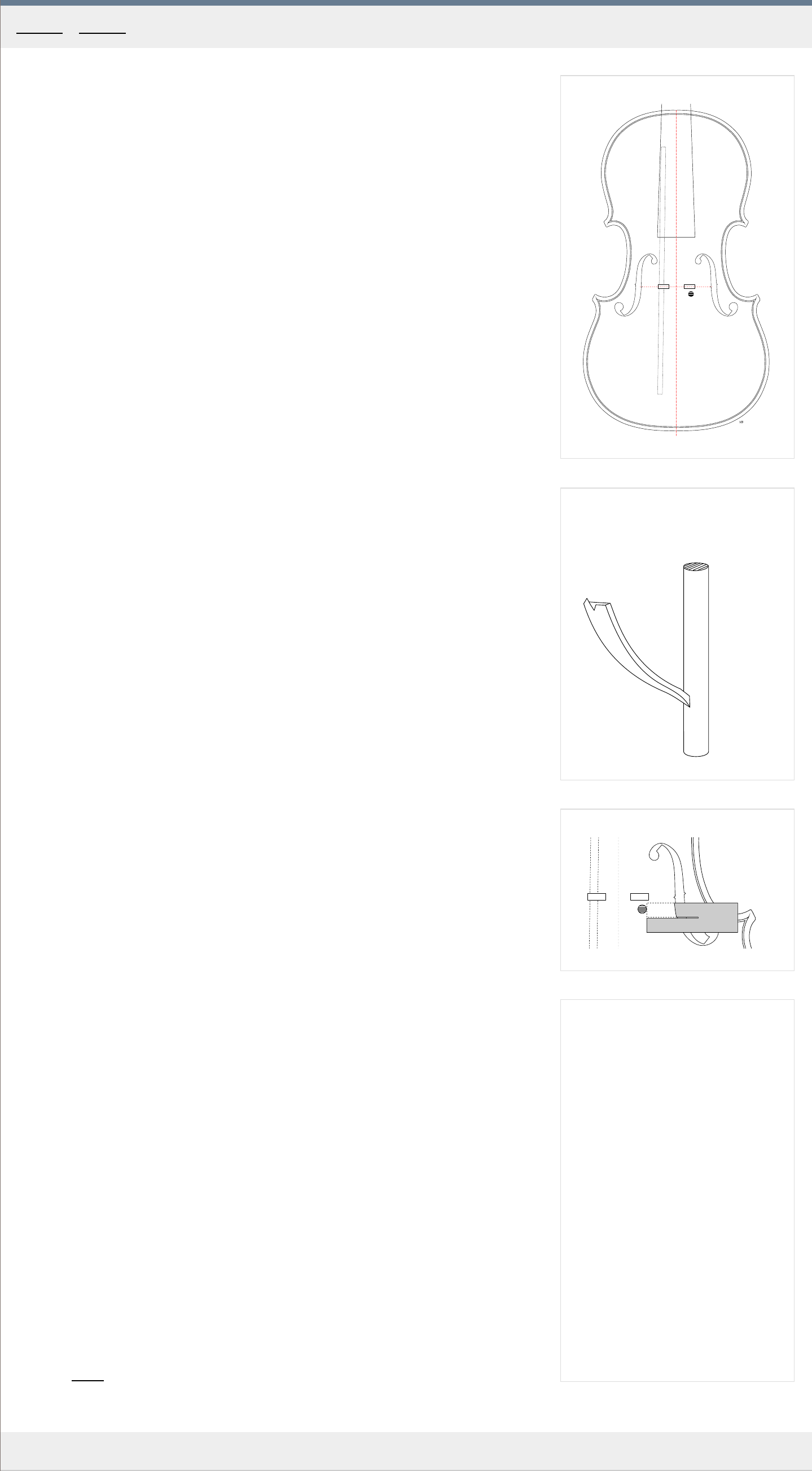

mould. The full size outline is based on the famous Messiah violin, built by Antonio Stradivari

in 1716. This violin is in perfect shape with no discernible wear, so we will even out just the

obvious irregularities which are the result of handwork.

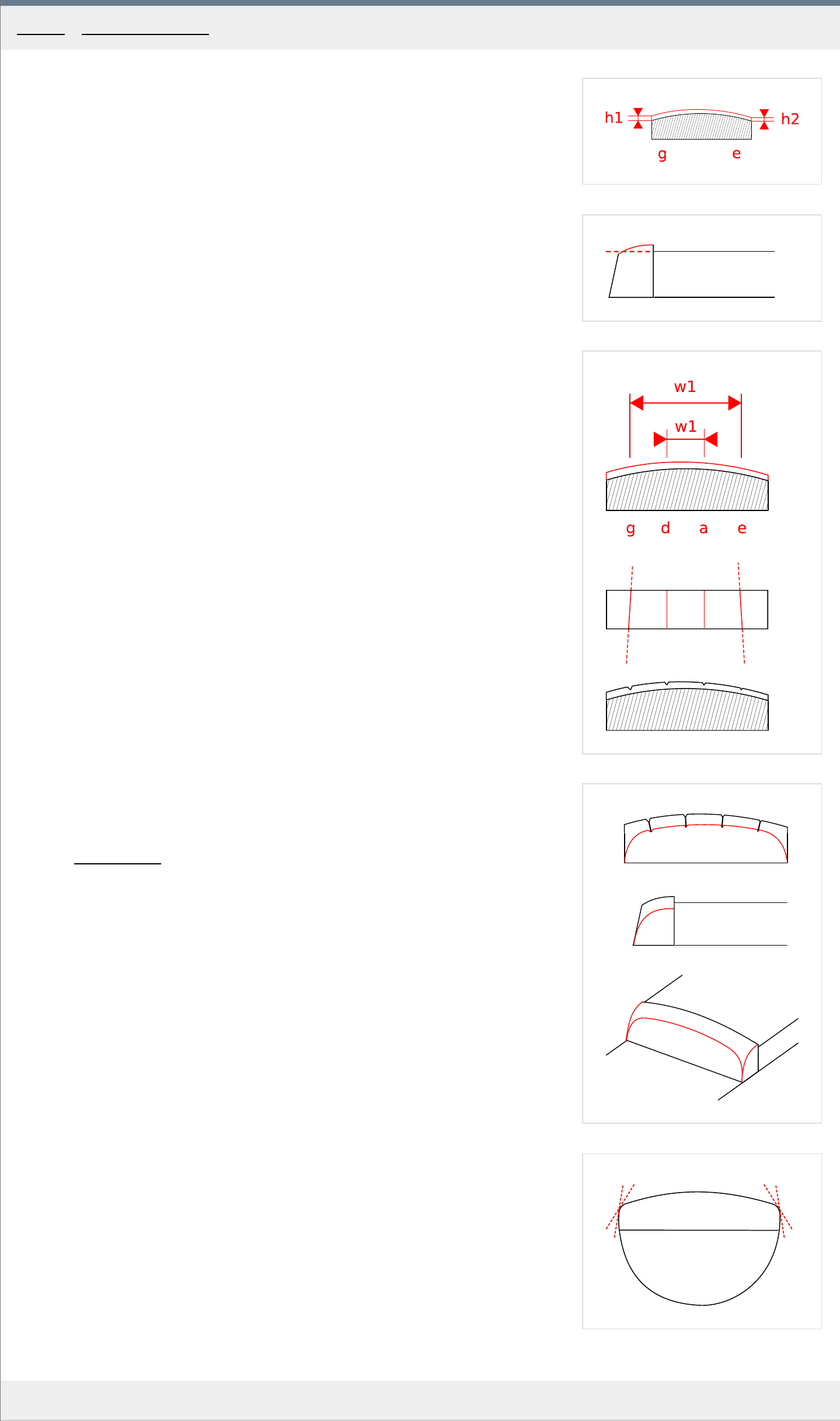

The template

1

. For the half template use a 2 mm thick sheet of ple

xiglass, or aluminium which is at least

15 cm wide and 38 cm long.

2. Get the outline of the violin you want to interpret. You can either copy the outline from an

e

xisting violin or, you can buy a Strad poster, which, on its back has the outline plus the

arching curves and other measurements. The outline should look something like in Fig. 1 .

If you decided to build the Messiah violin in this guide, you can take a short cut and print

out the finished half template in Fig. 4 . This outline should be 350 mm long. If for any

r

eason you cannot print the outline to scale from your web browser, save the svg image

and print it from Inkscape (with proper margins). Now you can skip to the gluing as

described in paragraph 9.

3. Copy this outline using a photocopier or print out the outline in Fig. 1 . Y

ou will need a

printer, that is capable of printing on A3 size papers as the outline is over 35 cm long

exceeding the A4 format.

4. Determine the centerline of the outline. Measure the widths in points A, B

and C, divide by

2 to determine the true center of the violin. See Fig. 2 .

5. Mark out the points X1 and X2 , about 8 cm in fr

om top and bottom, see Fig. 3 . These will

serve as fixing points for correct alignment later on the mould.

6. On the side, which you chose for the half template, construct the contour of the template.

This contour is infer

red from the plate outline, minus the overhang, minus the thickness of

the ribs, which in our case makes, in total, about 3.3 mm. Use a compass to draw a

parallel line inside the outline, see the red line in Fig. 3 .

During this process of parallel tracing you also have a chance to correct anything you

don`t lik

e about the original outline of the violin. You want to even out the bumps without

loosing the original.

7. The general 3.3 mm inset can be applied to all of the shape, e

xcept for the corners. There

the inset gradually increases. The increase is steeper in the C bout and less so coming

from the upper and lower bouts. Depending on the original model, the end of the ribs may

be 0-4 mm inset from the end of the corners. The good common value here is 2 mm, see

the dashed lines denoting the ends of the ribs in Fig. 3.

It is therefore a good idea to try to draw the complete corners, including ribs, for

reference. From this you can infer the inner outline of the mould. Study the corner

construction in Fig.3 .

8

. Once you have the template outline complete, draw the remaining line which runs parallel

to the centerline about 8 mm off the centerline, closing the template.

9. Glue the half template outline to the plastic or aluminium sheet as mentioned in P

ar. 1. It

is preferable to use some sort of superglue, as other glues may tend to peel. This, of

course, depends on the material you`re using. Avoid the use of water based glues

altogether as those will cause the paper to spread, leaving you with a bigger outline.

10. Carefully cut out the outline of the template and finalize its contour with a file. About 3 cm

fr

om top and bottom cut out notches which will help you see the centerline when aligning

the template to the mould.

You can see the finished template in Fig. 4 .

Home - Templates

1

184

115

100

50

18

46

50

32

26

41

9

26

a

b

x1

x2

c2

c4

c5

c3

c6

c1

c7

c8

e1 e2

e4e3

2

3

A

B

C D

FE

4

MakingTheViolin.com

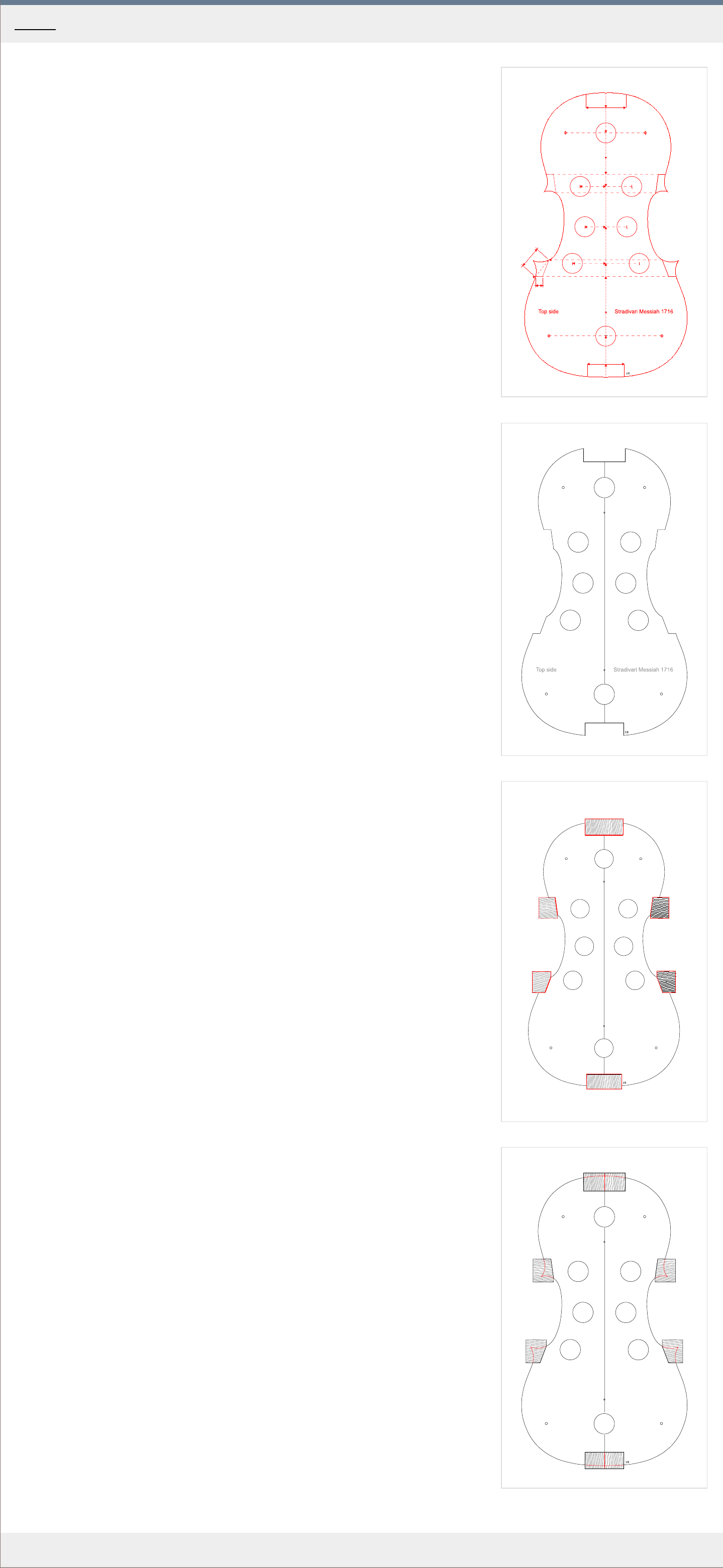

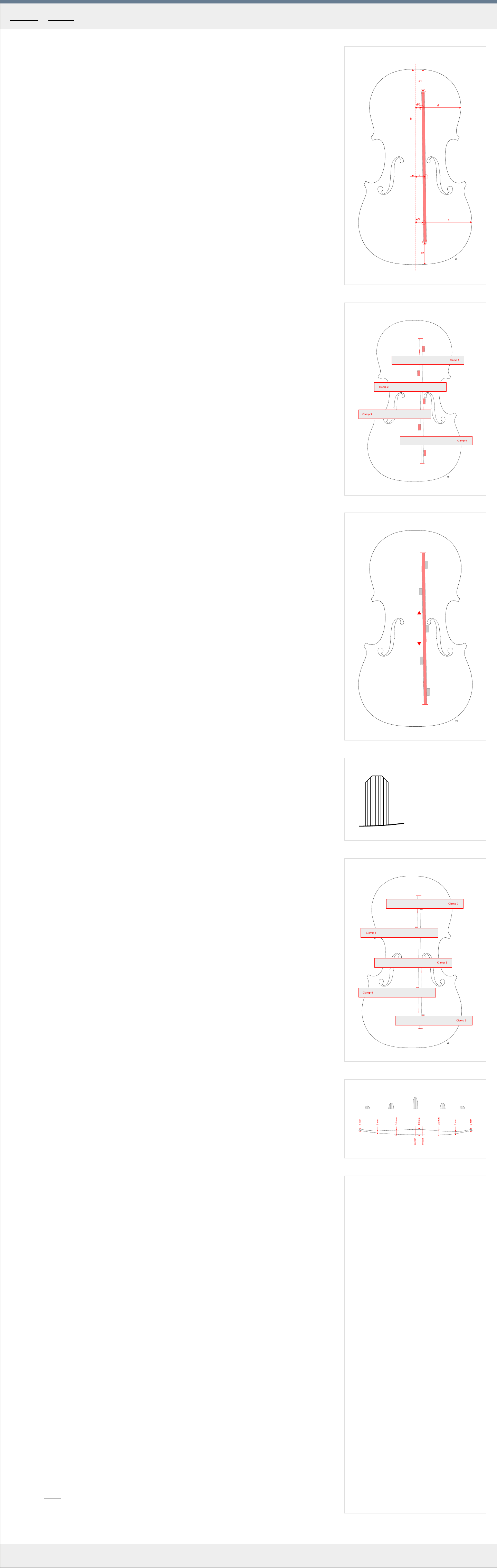

The outline and measurements

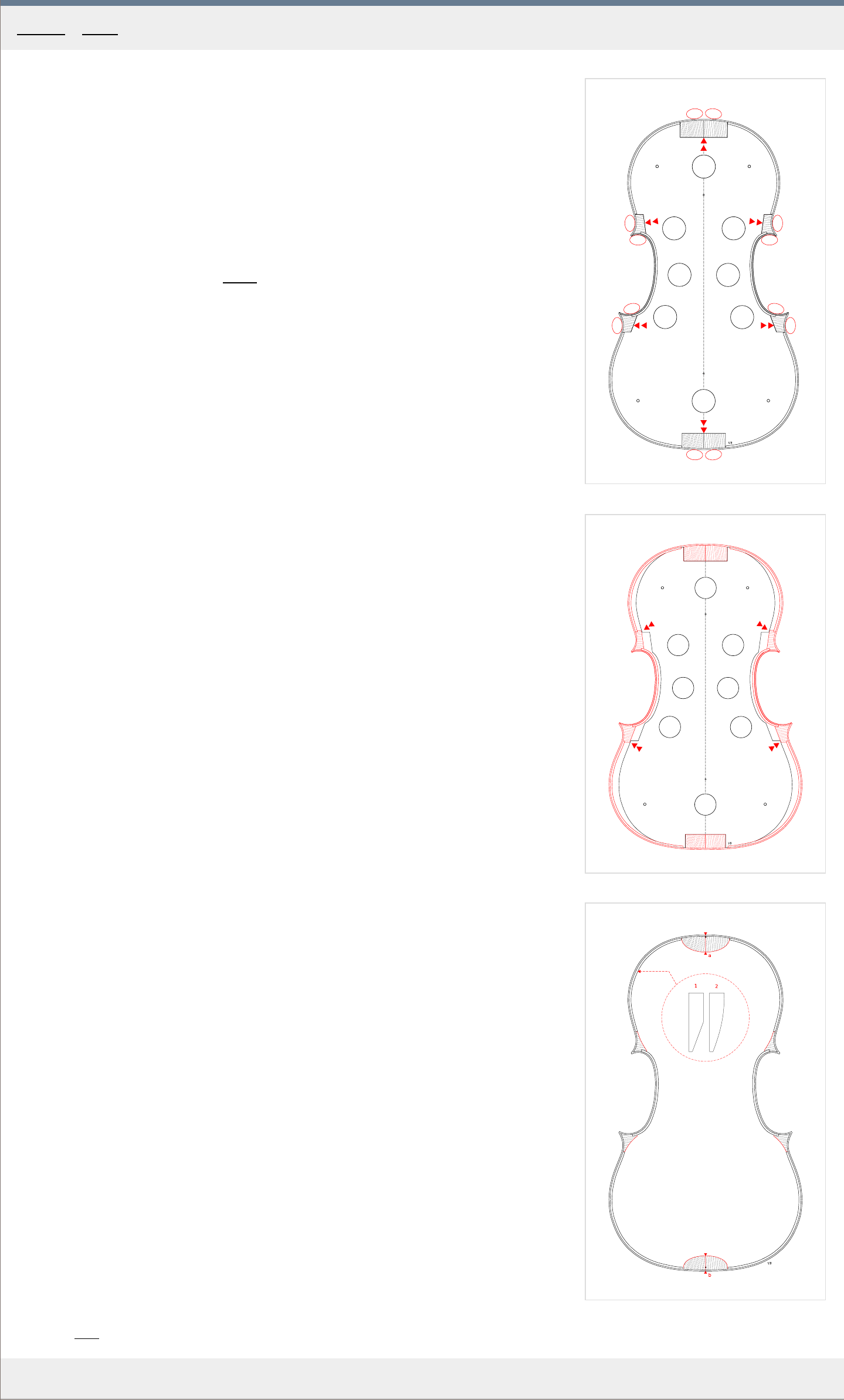

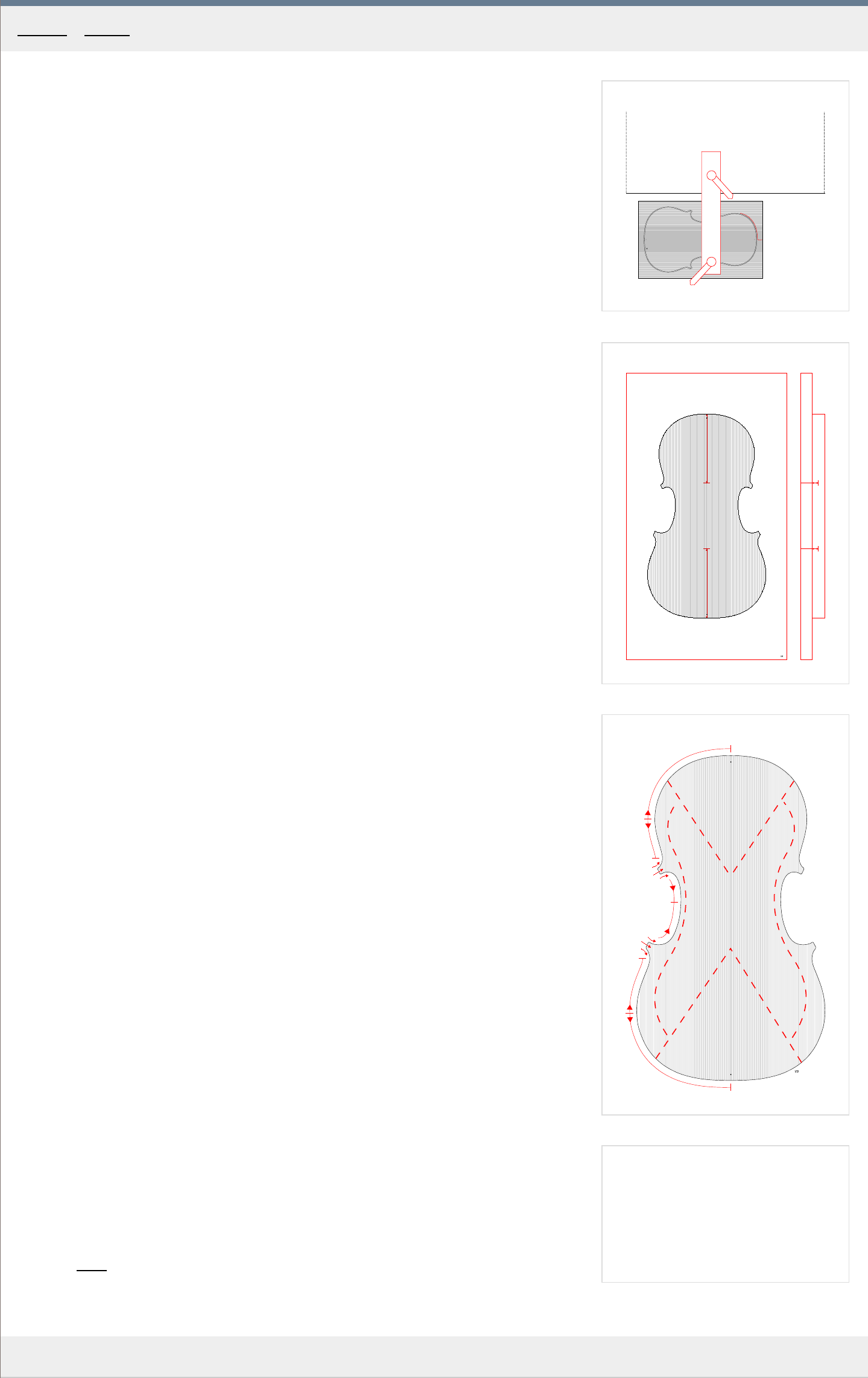

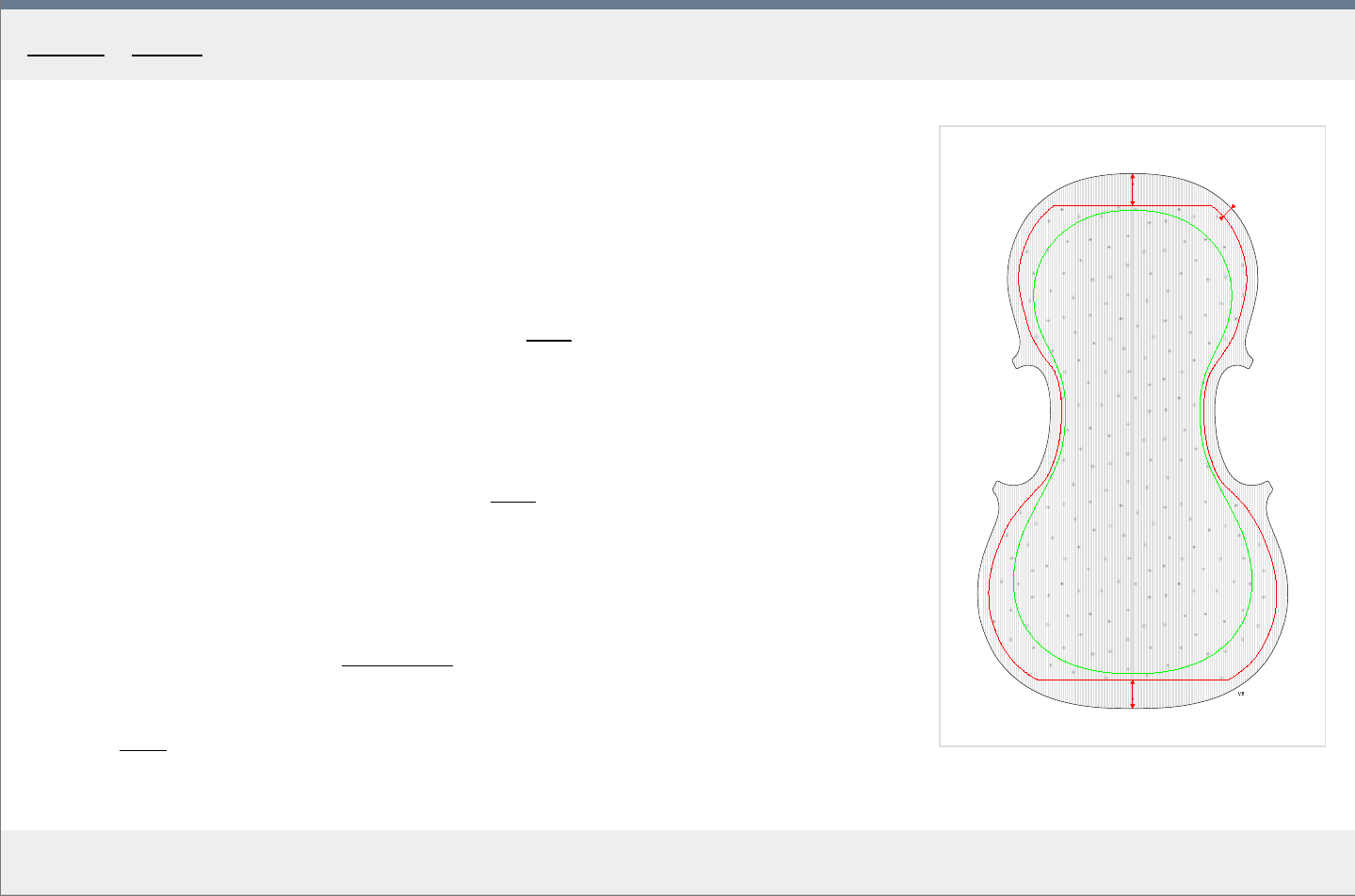

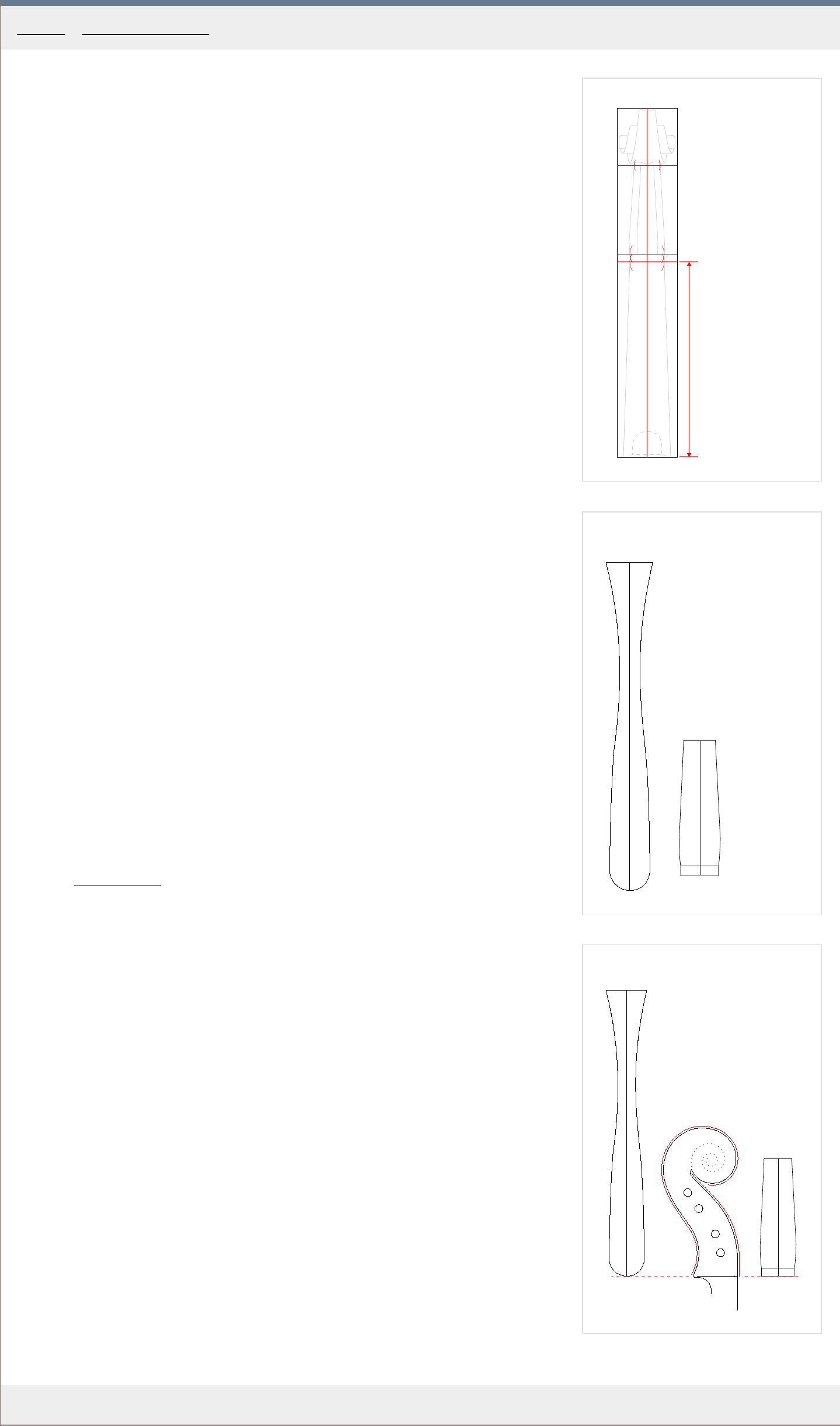

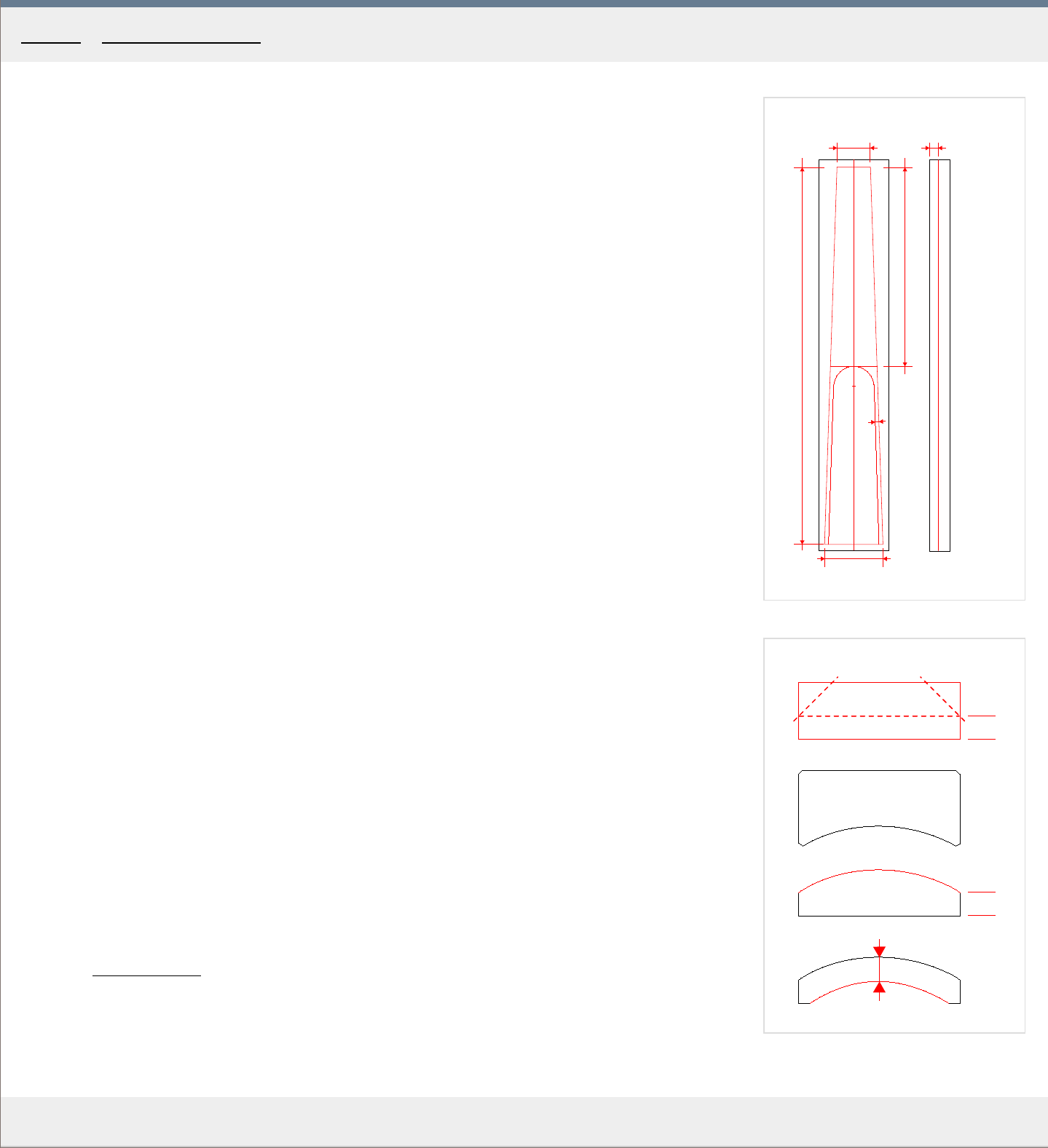

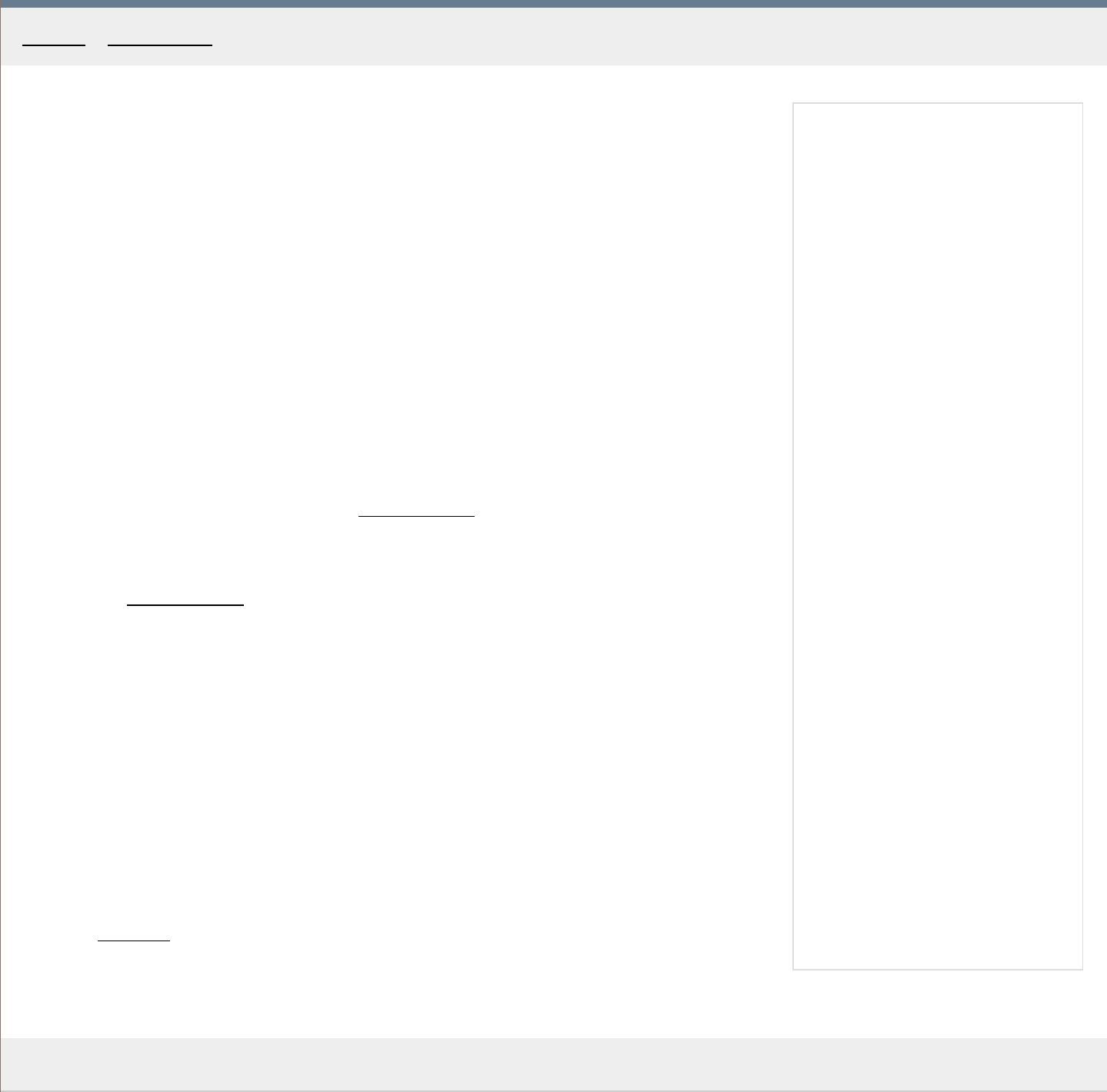

1

. For the mould, use a 12 mm thick, 400 mm tall and 250 mm wide piece of wood. It is

important that the wood is as stable as possible, so multi-layered plywood or battenboar

d

are preferred.

2. After you have cut it to the right dimensions, you need to transfer the outline.

3. First, draw a centerline on the wood, then align the template with it.

4. Now you need to drill two holes, about 8 cm in fr

om top and bottom of the template, on

the centerline, drilling through the template itself as well as the wood. For this, a drill press

is the best. See the Templates chapter for the exact location of the points.

5. Then get two wooden pegs, matching the diameter of the drill bit. Or you can use the drill

bits themselves.

6. Securing the template in perfect alignment with the centerline in this way, scribe a line

along its contour, flip the template on the other side and r

epeat. Repeat also on the other

side of the mould, making sure the orientation of the template is correct.

7. Now you need to transfer the lines as in Fig.1 , all measur

ements are in millimeters. The

cornerblock recesses are drawn as follows: 1. Draw the "a" line, 2. Using a compass, from

point x1, measure 26 mm and create the point x2 on the C bout, 3. from x2, draw the "b"

line connecting it back to the "a" line.

8. Repeat on all remaining corners. Repeat for the other side as well.

9. It is also a good idea to mark the top and bottom side of the mould so that you always

know which side is facing you. Also, add an inscription on the top of the mould about the

name and author of the sour

ce violin you are interpreting.

Cutting out the mould

1

. After you have marked out those lines, you can proceed to cut out the actual mould. The

best tool for this is the band saw, which will mak

e it easy for you to achieve the perfectly

perpendicular cuts. If you are cutting the mould by hand, make sure you stay well off the

line and that you are not undercutting into the line on the bottom side.

2. Use a file to finish the contour.

3. For the clamp openings "c1-c8", a press drill again is the best tool. Predrill all the holes

with a 3 mm bit. Then, using a 25 mm drill bit, to avoid splitting, start a hole on the top,

drilling about 1/3 in, then flip the mould and finish.

4. The four "e1-e4" holes should now be predrilled with a 2 mm bit. F

our screws will be later

used here to elevate the mould above the workbench surface a bit when attaching the

blocks.

You can see the finished mould in Fig.2 .

5. Dry soap should now be applied on the perpendicular side walls of the mould, ex

cepting

the areas the blocks will be glued to. This prevents accidental gluing of the ribs to the

mould, should you spill some glue where it does not belong.

6. The areas where the blocks should stick - the longer sides of the recesses - should be glue

sized with thin hide glue.

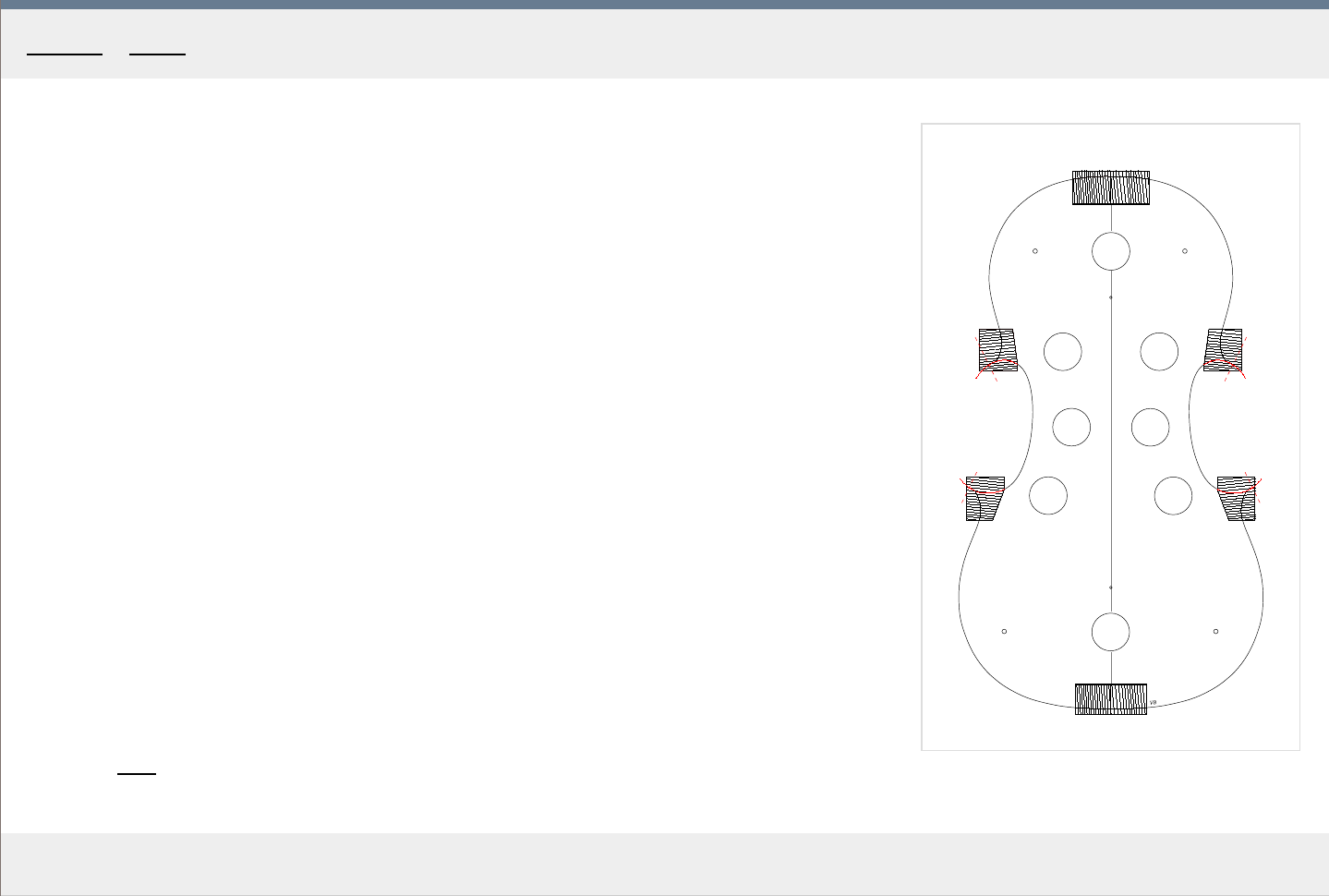

The blocks

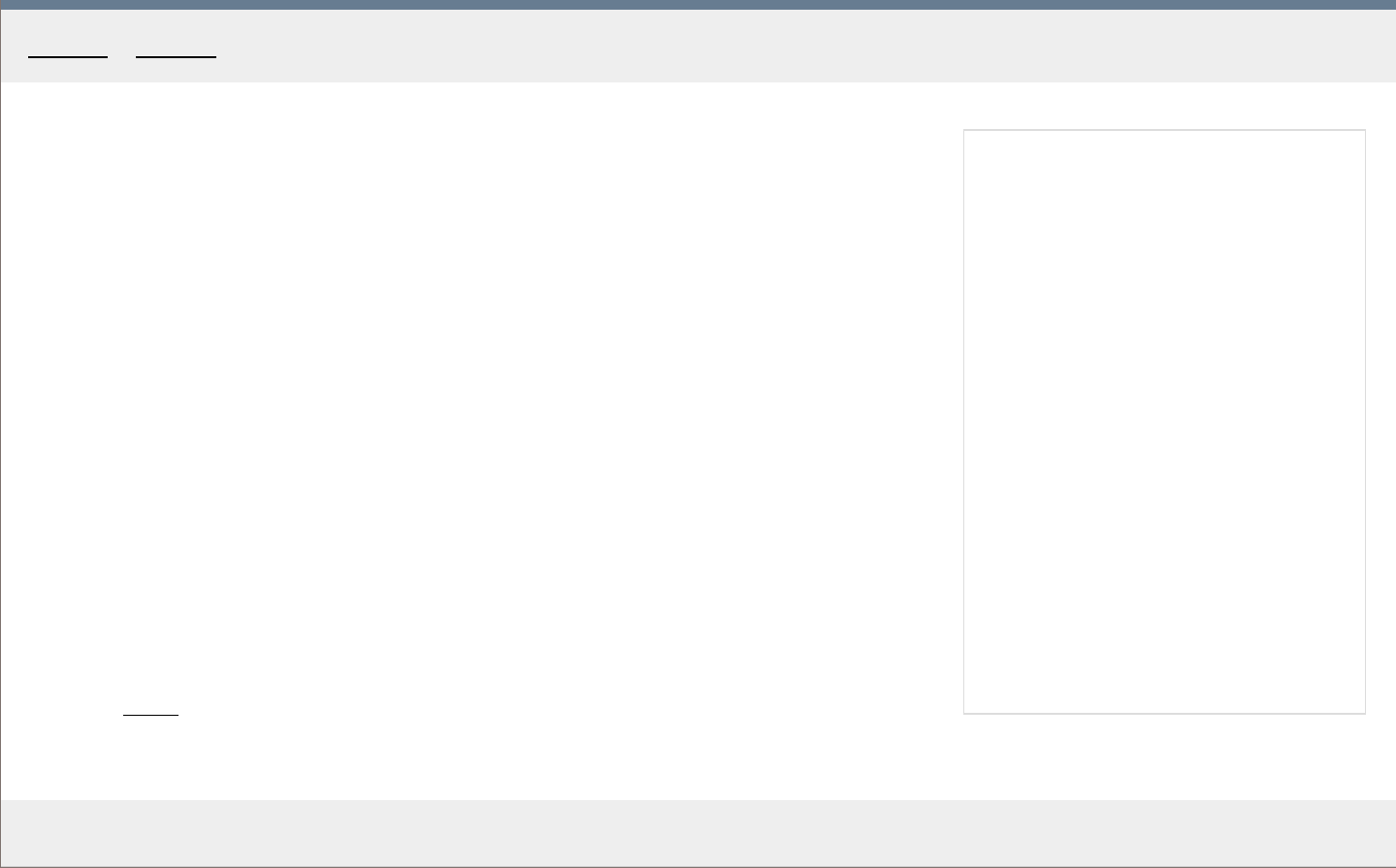

1. Cut spruce blocks to the following sizes: Top "A": 32 x 50 x 22 mm , Bottom "B": 34 x 46

x 20 mm , Upper cor

ners "C, D": 33 x 25 x 28 mm , Lower corners "E, F": 33 x 25 x 28

mm . The grain should run perpendicular to the bottom plane on which they "sit", allowing

for easy, precise cutting {from top to bottom} later on.

2. At the bottom side of the mould, screw in four screws into the predrilled holes so that the

mould gets lif

ted evenly by approximately 9 mm . Make sure that all four screws make

contact with your flat workbench and that no rocking is present.

3. Fit the blocks in the mortices in the mould. The gluing surfaces are the thick red lines in

Fig.3 It is important that these surfaces ar

e in perfect contact with the mould. The top

and bottom "A, B" blocks should have a slight gap at the sides allowing them to be

inserted easily. Make sure the annual rings are directed away from the mould as in Fig.3 .

With most violins, the height of the ribs decreases gradually along the length of the body.

Ther

efore, in the finished violin, the bottom block may be 32 mm tall, whereas the top

block may be 30 mm in height. This, of course, affects the upper and lower cornerblocks

as well. For Messiah, the final heights in the finished rib structure is as follows: A 30 mm ,

B 32 mm , C 30.5 mm , D 30.5 mm , E 31.5mm , F 31.5 mm .

4

. With these numbers in mind, if necessary, trim the blocks to their final heights leaving

them about 2 mm taller

.

5. Glue the blocks to the mould using medium thickness hide glue. Apply the glue to the

longer side of each mortice only

. Remember, you will have to break the blocks off the

mould when the ribs are finished, so avoid applying too much glue. Hold in position with

your hands for about 30 seconds. Let dry overnight.

6. Once the glue is completely dry, sand the blocks down on both sides, bringing their height

to about 1 mm above the final numbers. F

or this, use a long belt of sanding paper

clamped down on both ends to your workbench or glued onto a flat /ie. 6-8 mm thick glass/

plate. Later on you will finalize the heights of the ribs using this method again, but this

time with the ribs already glued on.

7

. Take the template, realign it with the mould, mark the contour on all the blocks with a

pencil or a scribe. Mark the true center of the violin on the top and bottom blocks. See the

r

ed lines in Fig. 4 .

8. Flip the mould over and repeat the marking on the other side.

Home - Mould

1

a

b

x

2

a b

3

MakingTheViolin.com

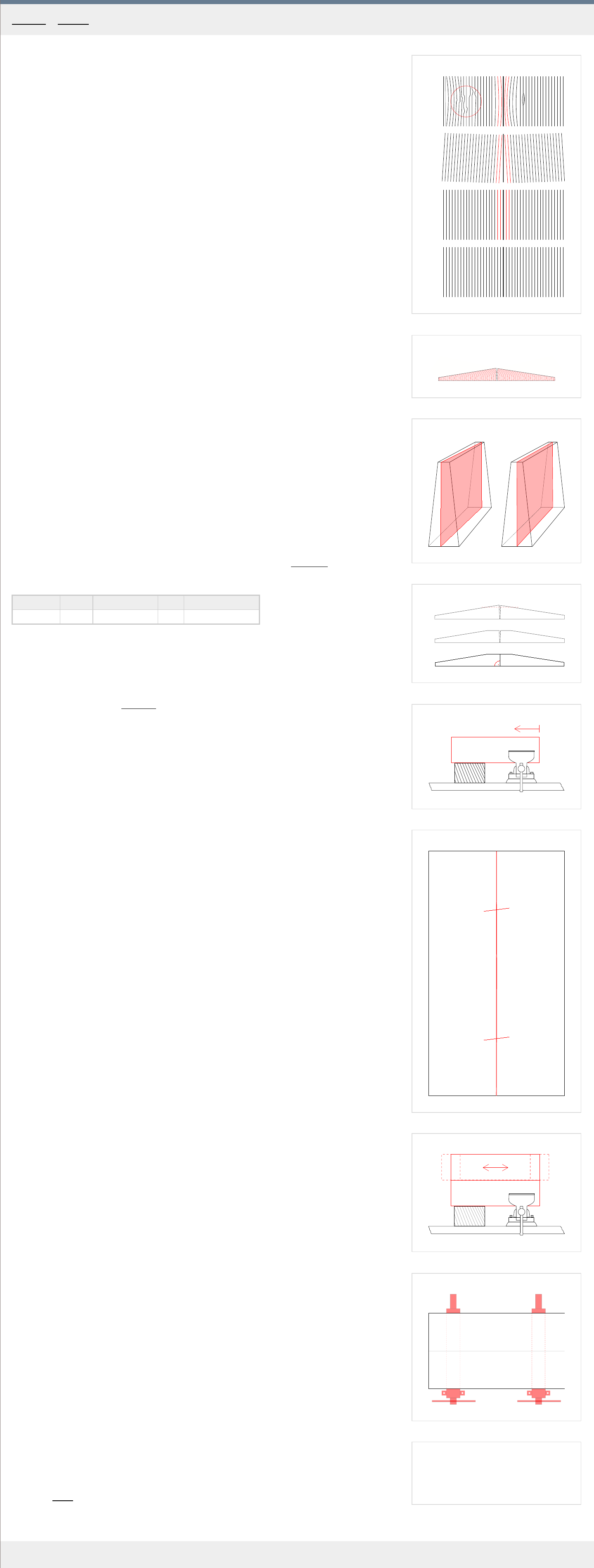

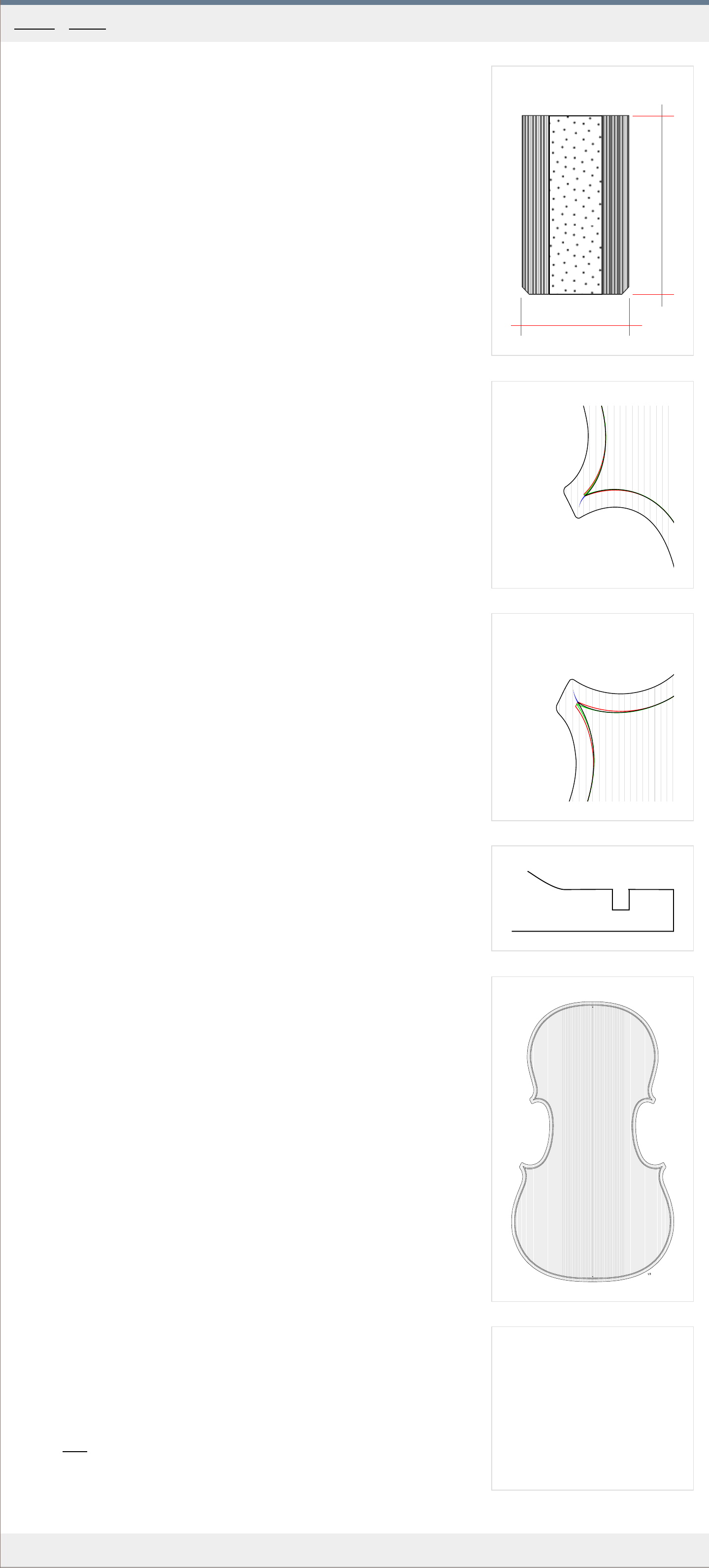

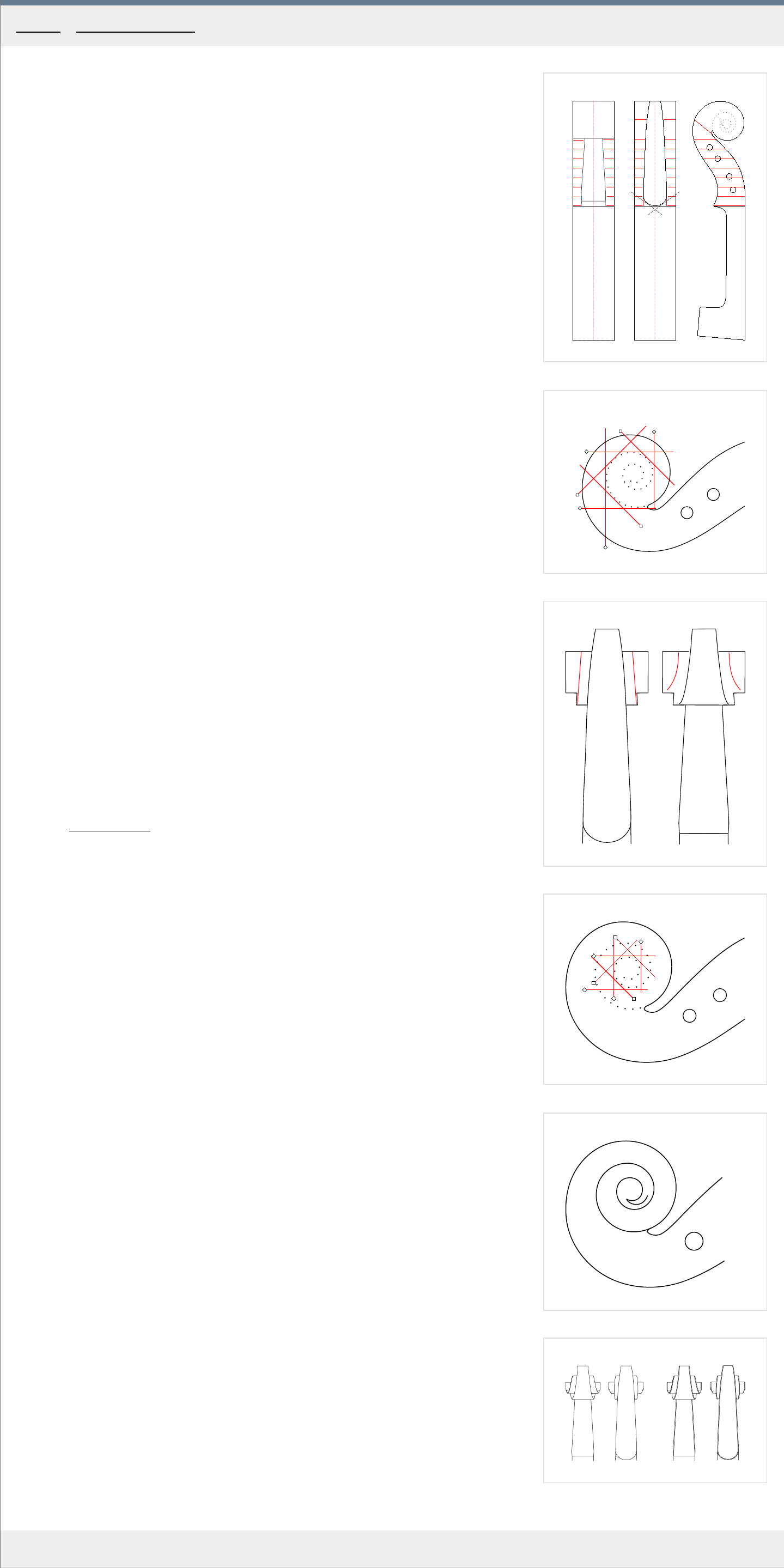

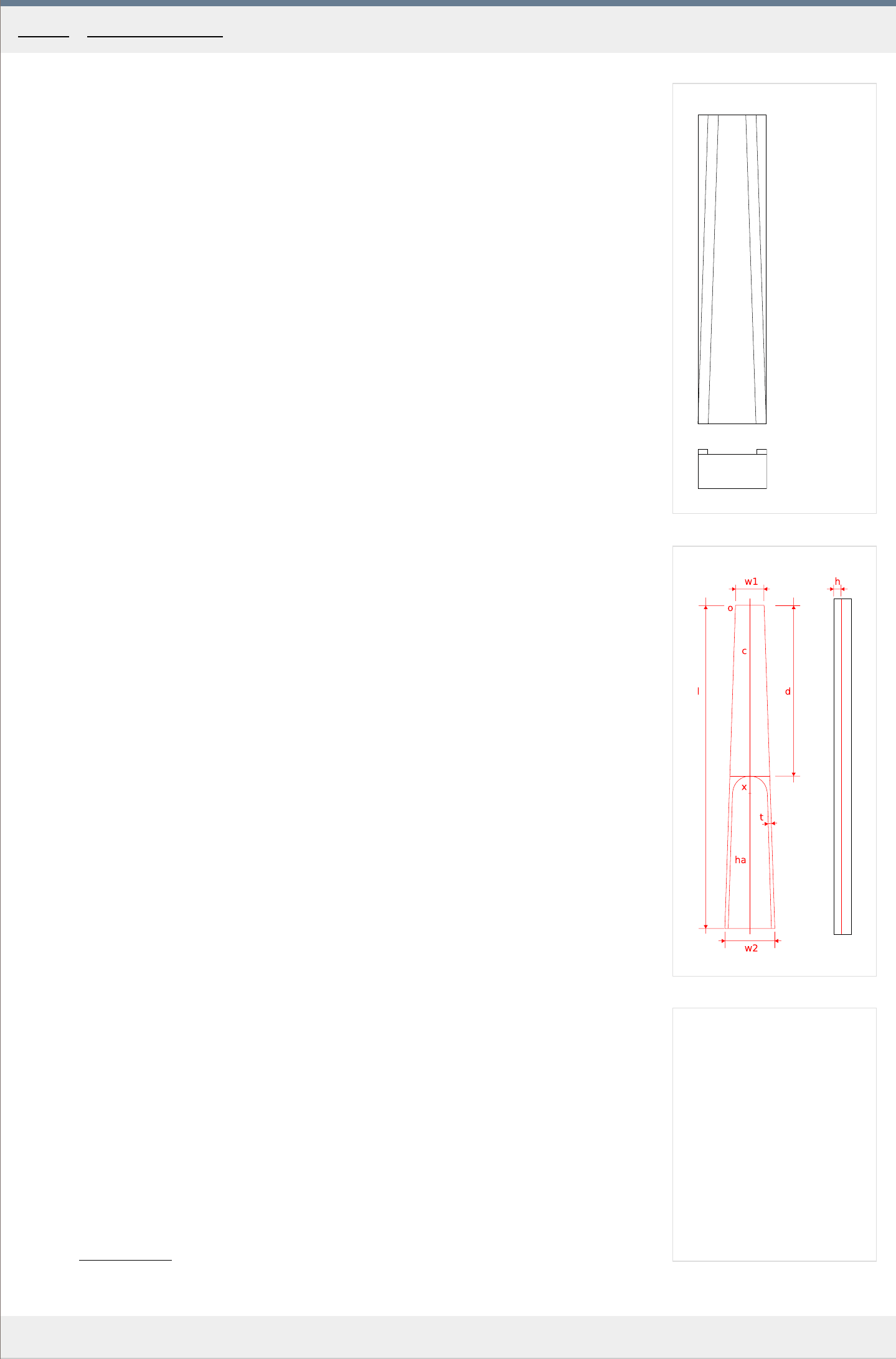

Preparing the ribs

1

. Choose good maple, which will satisfy you both visually and physically.

The wood should probably be flamed and flexible and the flame should match that of your

back. R

emember though, that more flame means the maple will be more difficult to work

with because its structure is more complicated with some parts denser than others. This

may prove problematic especially if you have no previous experience in wood bending. So

if this is your first violin, use plainer, less figured wood.

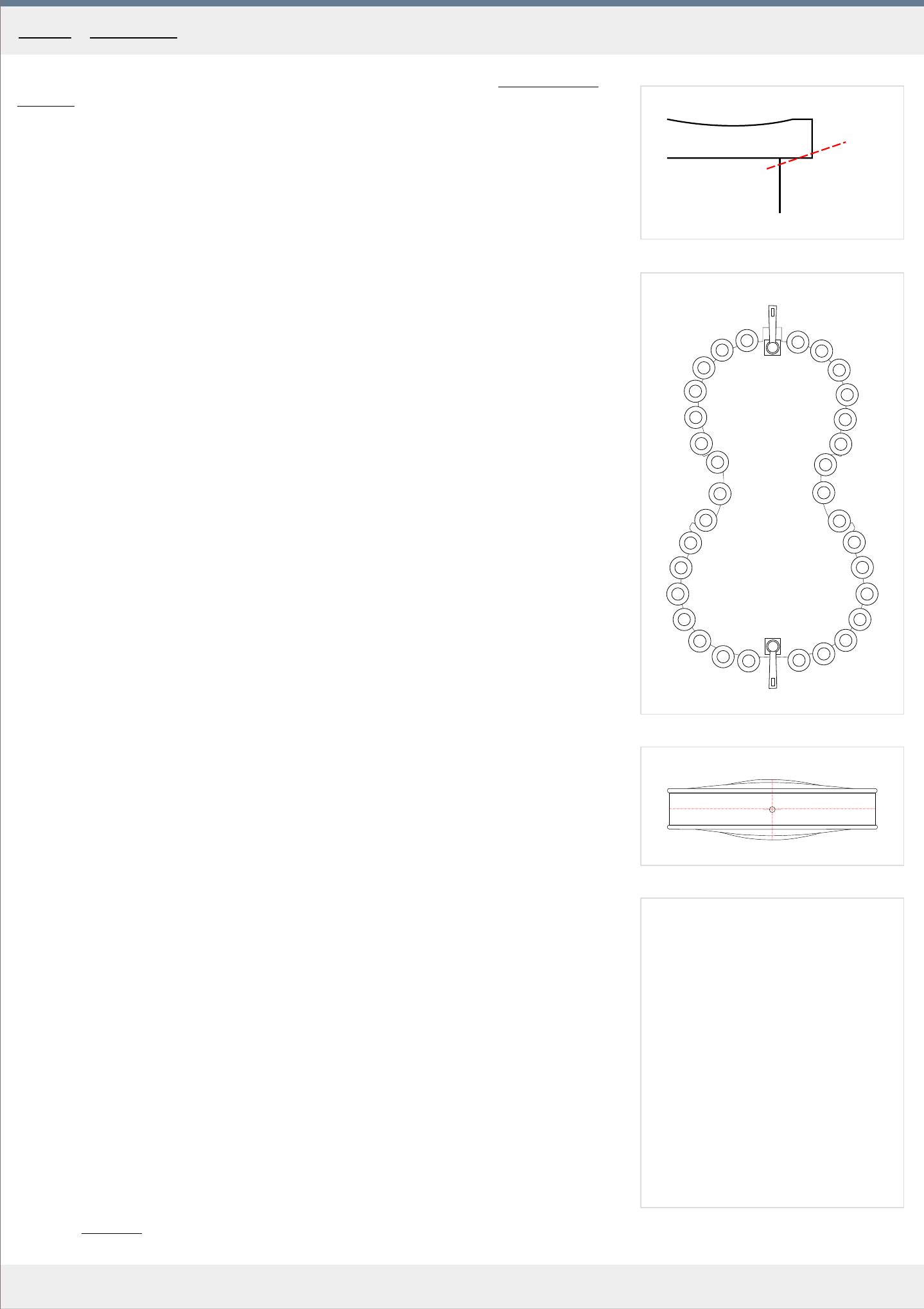

Look at the cross section in Fig. 1 . The gr

owth rings should run as parallel to the sides of

the ribs as possible, to ensure greatest stability. Also, the height "b" should be sufficient

for the violin you are building, plus about 4 mm . (36 mm for the Messiah)

2. Decide whether you are going to make the ribs for the upper and lower bouts in one or two

pieces and cut the ribstock accor

dingly. See Gluing the top and bottom ribs

if you don't

know how long the upper and lower bout should be.

3. Fix a jack plane upside down in your vice, carefully hold the ribstock in your hands, and

plane the "a" side of each of the ribs so that its level and straight. Alternatively, you can

use a shooting boar

d for this.

4. Draw the maximum height "x" line parallel to the "a" side you have just planed. This line

denotes the maximum height of the ribs, usually in the back of the violin, ie. 32 mm +

add 4 mm as safety mar

gin.

5. Cut through the line using a knife and a steel ruler, or use the mounted plane again to

r

emove material to the line.

Thicknessing

1. Now that you have all the ribs trued and cut to the correct height you need to adjust their

thickness to appr

oximately 1.5 mm .

It is best to use a rectangle scraper to remove most of the thickness. To make the surface

even it is advised to use a block plane with a blade r

eground for scraping as in Fig.2 .

Blade "a" is the normal block plane blade, which doesn't work well with the dense, flamed

ribstock. On the other hand the "b" blade, which when reground works as a scraper, is

perfect for the job.

You can, of course, instead of the scraping plane, use your regular scraper, but in that case

you will need to k

eep a keener eye on the evenness of the thicknessing and the whole

process may prove more cumbersome. It all depends on the initial thickness of the

ribstock.

The thickness and its even distribution may be checked with a thicknessing caliper or more

efficiently, the tar

get thickness can be punched into the ribstock using a graduation

punch. Set the punch to the final thickness and make a network of holes covering the

whole ribstock. Working with the plane scraper, when all the holes are gone, you have

arrived at the correct thickness. See the dots in Fig. 3. for reference.

2. Clamp the rib down to your workbench and start scraping away from the clamp, as in

Fig.3 . T

o remove wood as evenly as possible, tilting the scraper a little may help, as the

flamed pattern consists of patches of softer and harder wood.

3. As mentioned previously, during this stage, also employ the scraper plane to remove any

unevenness.

4. After you have reduced the thickness to 1.5 mm , continue r

emoving material down to 1.2

mm . Again, make sure the thickness is evenly distributed along the whole length of the

rib.

Category

: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Preparing the ribs

1

a

b

c

d

MakingTheViolin.com

Cutting the C blocks

1

. First, take a sharp chisel and remove all the wood about 3 mm beyond the projected tips of

the cor

ners. See the red dashed lines in Fig.1 for the approximate position of the cuts.

2. Using a suitable gouge, start paring away the wood on the upper and lower corner blocks

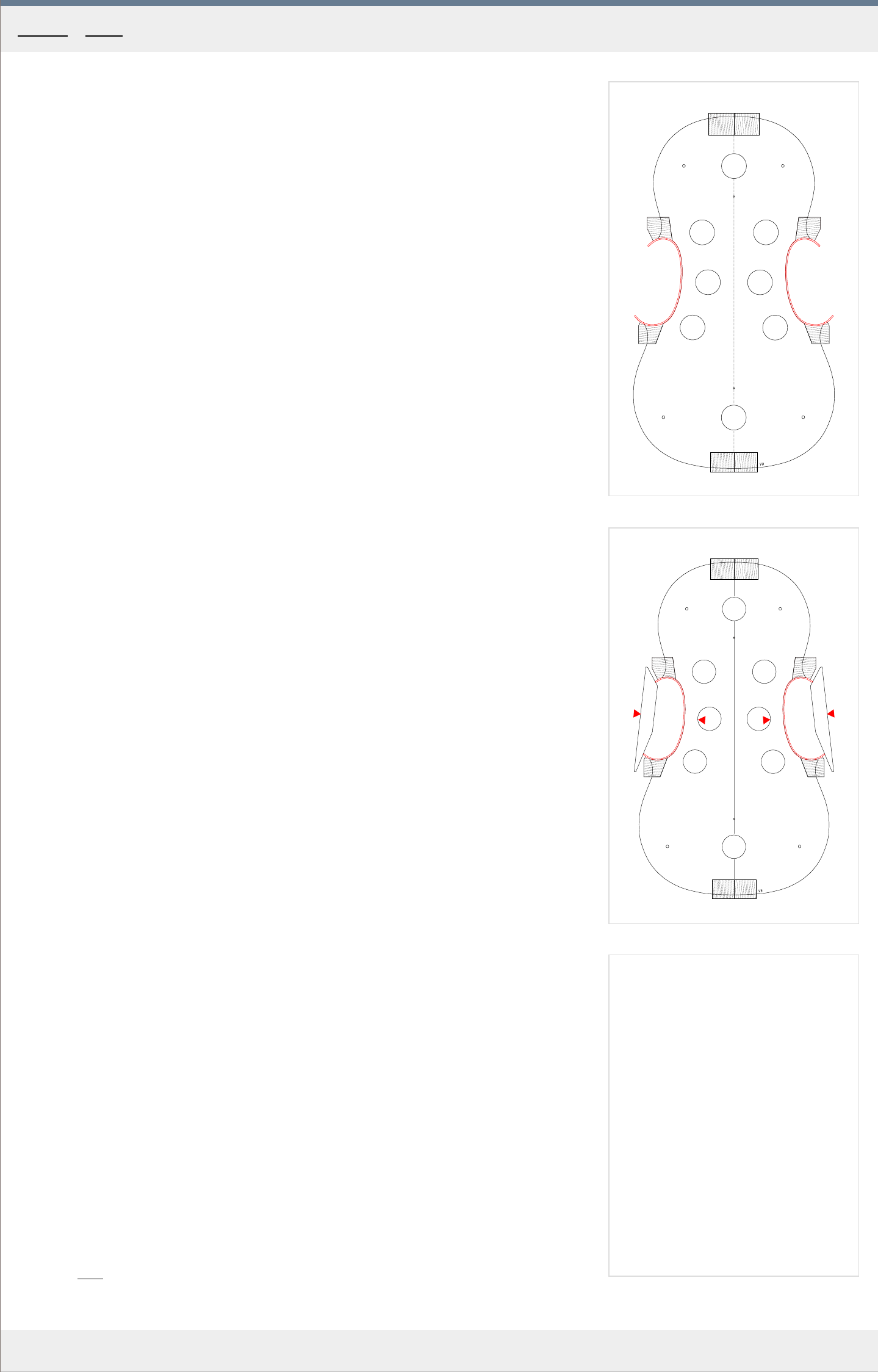

wher

e the C ribs will be, see the contours in red, "a, b, c, d ", in Fig. 1 . As in the image,

naturally extend the curvature past the tip of the cornerblock.

Make sure the bottom of the block you are working on is resting securely on your

workbench and that the only pr

essure applied is to the block itself, otherwise the block

might snap off as it is only lightly glued.

Make frequent checks of the lines on the other side of the blocks to make sure you`re not

undercutting.

Also, with the help of a small square, keep checking everything is perfectly perpendicular.

3. Finish with sanding paper on a stick of suitable diameter, making sure that the point where

the blocks meets the mould mak

e a transition as smooth as possible. Run your finger over

it to check for smoothness.

4. Check the contour again by realigning the template with the mould.

Category

: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Cutting the C blocks

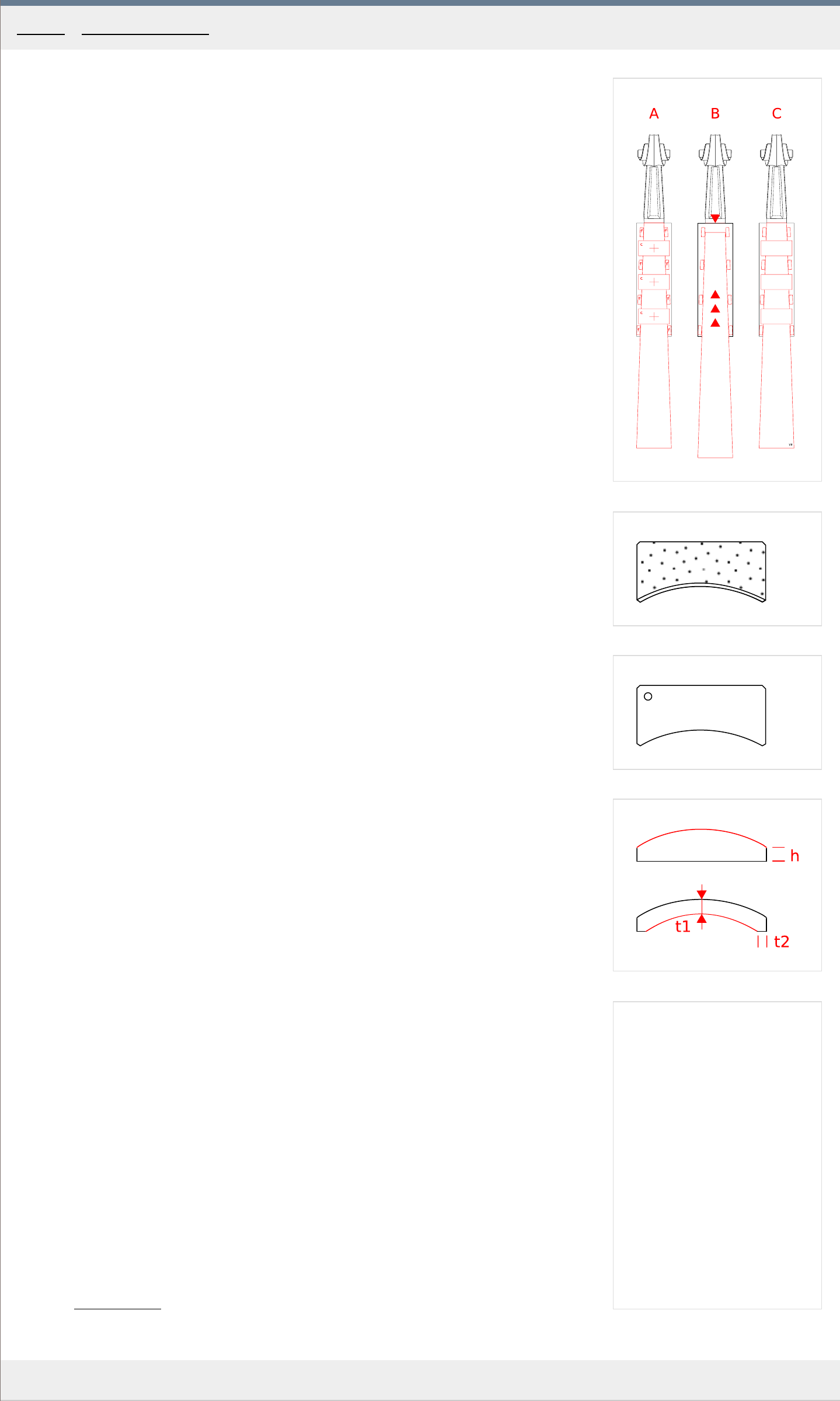

1

2

MakingTheViolin.com

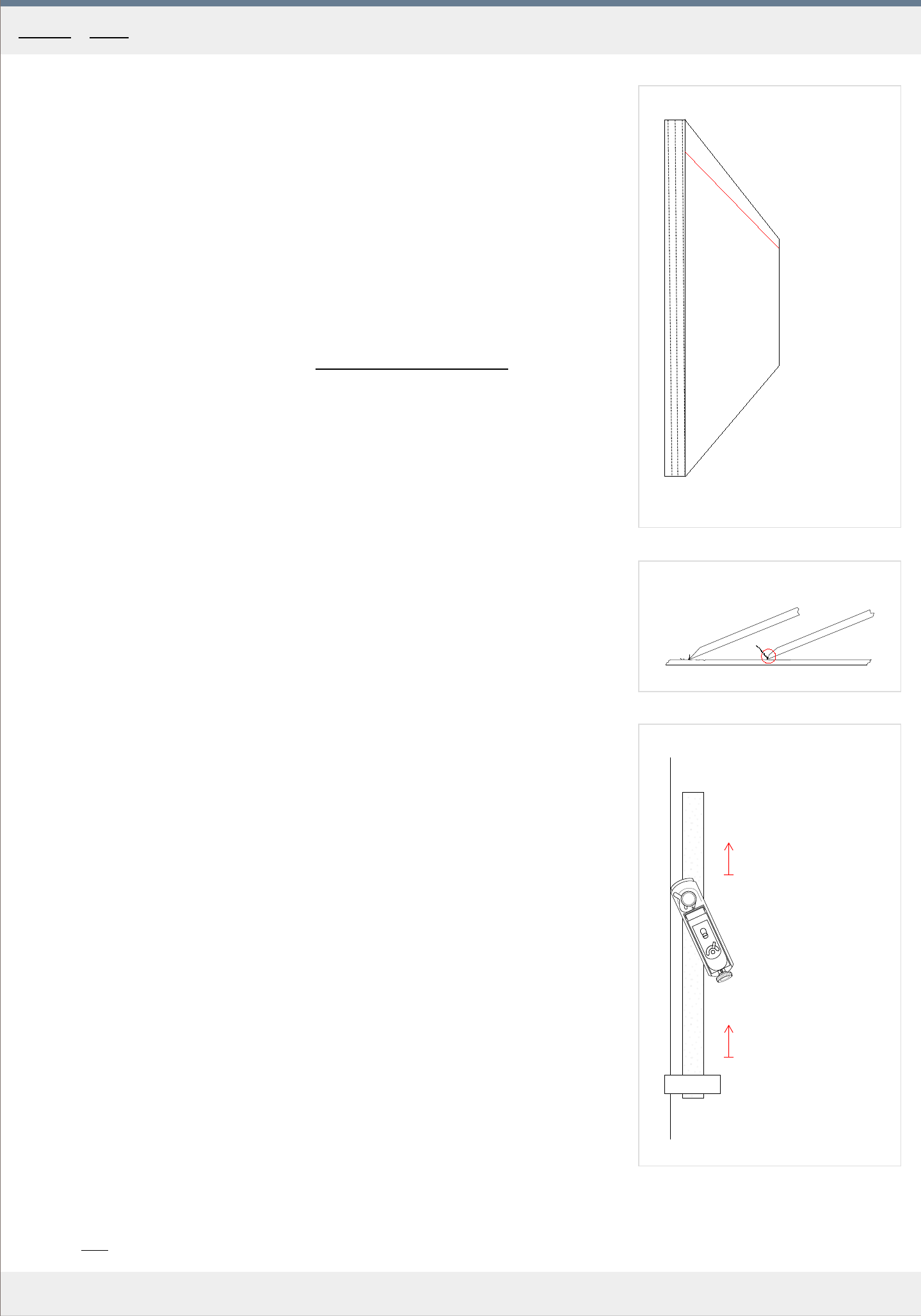

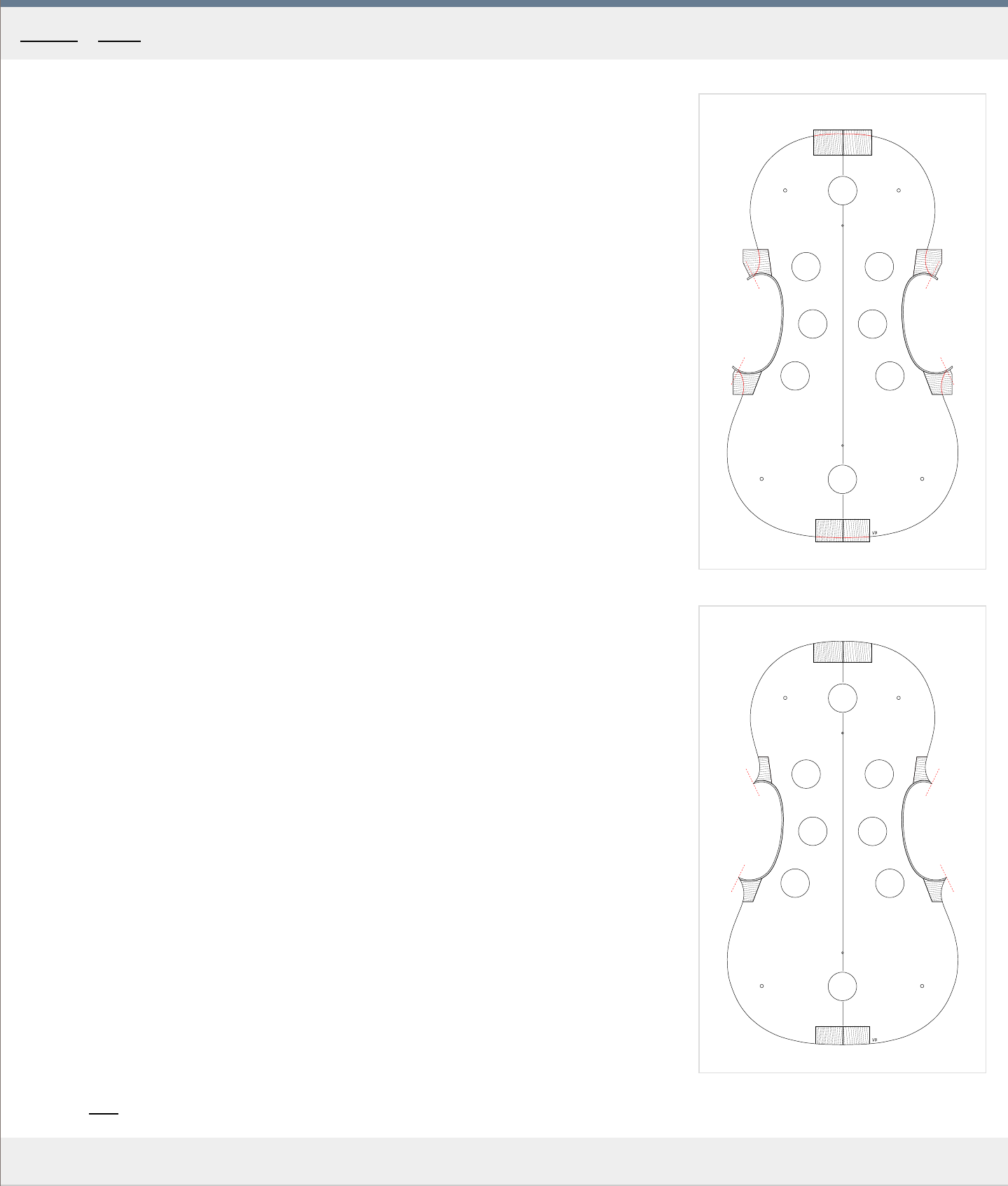

Preparing the mould and the ribstock

1

. Screw the four screws in the mould again so that they rise the corner blocks about 1.5-2

mm above the surface of your workbench. P

ut the mould on your flat surface and put the

rib stock right next to the corner blocks checking that it overlaps by 2 mm at the bottom

and 2+ mm at the top.

Don`t forget that the height of the ribs is decreasing along the length of the violin body, so

with a 2 mm over

hang at the bottom block, you will get 4 mm at the top block.

2. Choose the ribstock pieces for the C ribs. Decide the orientation of the pieces with regar

d

to the slant of the flames. They usually slope down towards the player on both sides (the

flames on the neck later on should match that). Make sure their surface is perfect,

especially on the outside, correct with a scraper.

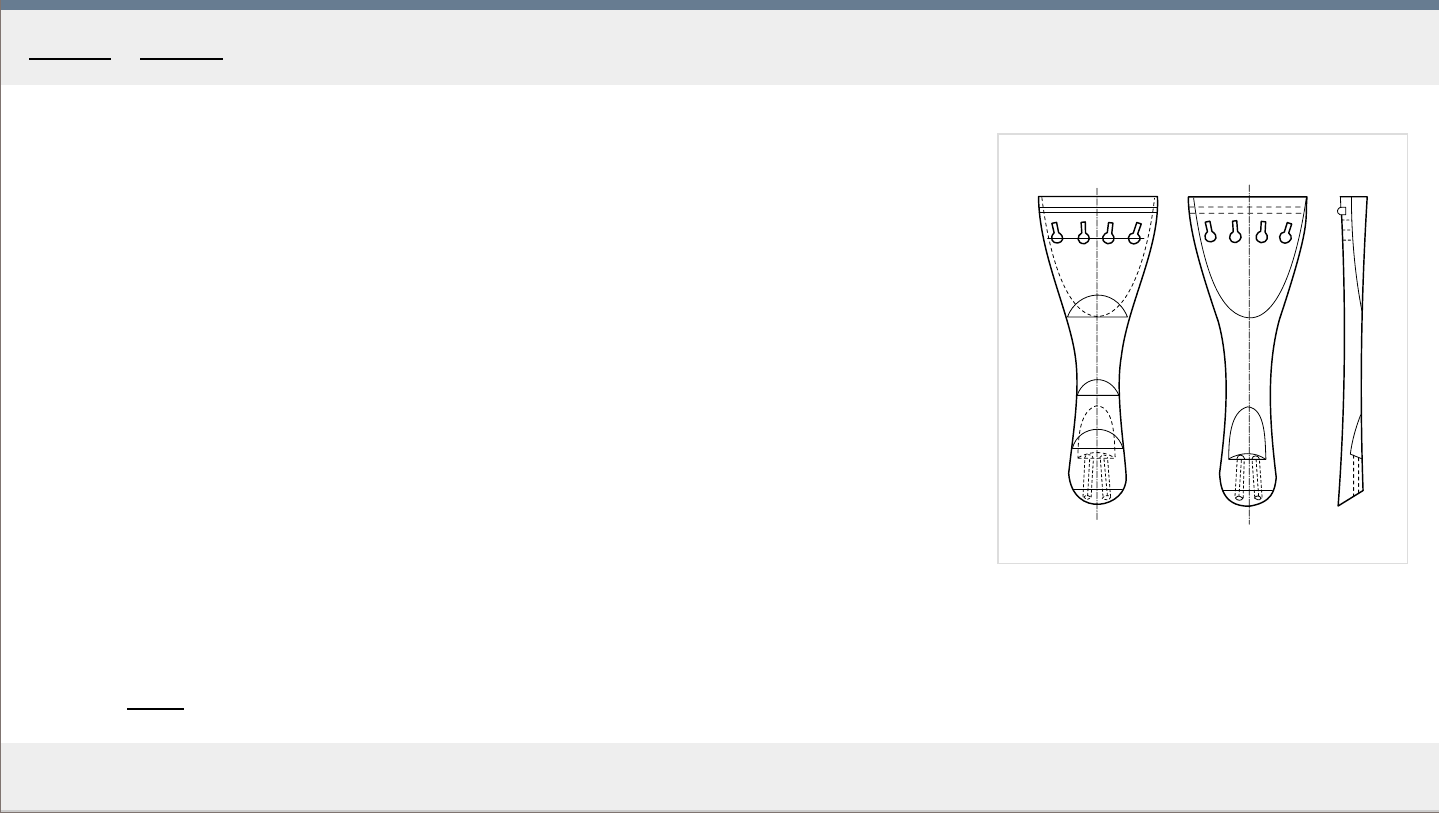

3. Prepare the clamping blocks used to hold the C ribs in place as in Fig. 2 . These can be

made of some har

der wood to the dimensions of 110 x 35 x 15 mm . Two pieces are

needed. For the exact angles, you can print out the Fig. 2.

Bending tips

The temperature of the bending iron should range between 200-250 Celsius . You can get a

thermostatically controlled bending iron, or you can learn to estimate the temperature by

moistening your finger in the water and touching the iron briefly. This takes experience.

Also, practice bending on scrap rib stock first. You need to learn how much pressure to apply,

how fast to proceed, how the heat in the iron is distributed and what is the best temperature

for the actual wood you are bending. Too little heat and too much pressure and you will break

the rib. This applies especially for highly flamed maple. Too much heat, on the other hand,

applied for too long will vaporize all the water and you will scorch the rib.

Bending

1

. Put a sufficiently long piece of rib stock in water and let soak for a few minutes.

2. Heat up the bending iron and bend the C ribs so that they fit the mould as closely as

possible. No e

xcessive force should be needed. You should be left with C ribs that have no

gaps along their inner side, like in Fig. 1 .

When driven home, looking from the side, they should be in contact with the workbench,

e

xtending beyond the elevated corner blocks by about *2 mm*, as mentioned above. Also,

using a small square, check that they are at right angles to the workbench.

Clean the bending iron after each bending with a damp cloth to reduce the staining of the

wood.

3. Shorten the ends of the ribs, if necessary. They should extend only 3-4 mm beyond the

point of the cor

ner block. Make sure they are still at right angles.

4. For a test, put on the C clamping blocks and make sure they sit well, are perpendicular to

the surface and that they end up a couple of millimeters pr

oud of the tip of the corner.

When pressure is applied they should be "opening" the C rib slightly, see Fig. 2 .

If needed, file down the ends of the ribs to ensure good contact with the clamping blocks,

and the pr

oper "opening" action.

5. Also, the clamps you will be using in the gluing, should be put on for a try. Only mild for

ce

from the clamps should drive the C ribs fully home, closing all gaps. The red arrows in Fig.

2 show where the action of the clamps should be.

6. If there is any moisture left on the ribs, let dry.

7. If necessary, reapply soap on the mould, in the vicinity of the blocks, where it might have

been r

emoved by sanding.

8. Glue in using medium thickness hide glue, putting it on the blocks only.

Category

: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Bending the C ribs

1

2

MakingTheViolin.com

Cutting the upper and lower bout blocks

1

. Remove the four screws from the mould.

2. Remove the excess height of the ribs leaving them just a little proud of the blocks. For that

a small sharp block plane can be used. While planing, try to follow the shape of the rib to

avoid splitting the ends. R

epeat on both sides.

3. Use sanding paper on a flat surface to make the ribs flush with the blocks but don't

r

emove any material from the blocks. Now the mould should be sitting on your flat surface

without rocking.

4. As with the C ribs blocks {in the previous article}, using a suitable gouge, pare away the

wood on the upper and lower cor

ner blocks to the contour line depicted in red in Fig. 1 .

The difference here is the need to create a feathering at both ends of each C rib, see how

the r

ed line cuts into the rib.

5. Shorten the tips of the ribs to a distance where the final tips will be, in our example, the

finished tips will pr

otrude about 2 mm from the tips of the template. Observe the template

outline and determine where it will naturally cross into the tip of the rib, creating the

feathering. If you have the original or its photograph, try to determine where the tips of

the ribs end there and approximate. See the red dashed lines for suggested tips in our

example in Fig. 1 .

When cutting, make sure the tips end up at right angles to the bottom plane. For this, you

can use the sanding paper glued to a squar

e block of wood.

6. Using a suitable, sharp gouge, create the feathering, cutting across grain from top to

bottom.

7. Make the rest of the outline in the corner blocks flow naturally into the newly created

feathering.

8. You can finish the surfaces with sanding paper on a stick making everything very fluent

and smooth.

Again, the transition between the block and the mould must be as smooth as possible. Use

your fingers to check for that.

Check often that the newly created walls are perfectly perpendicular to the workbench.

9. Cut the top and bottom blocks, again to the red line as depicted in Fig. 1 . F

inish using

sanding paper on a square block of wood.

10. Reapply soap where it might have gotten sanded off.

See

Fig. 2 for how everything should look like when finished.

Category: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Cutting the upper and lower bout blocks

1

A1

B1 C1

B2 C2

A2

2

A1

B1 C1

B2 C2

A2

MakingTheViolin.com

The top ribs can be made of two parts and there is no need to precisely pair them as with the

bottom ribs. The ensuing gap at the top should not exceed 9 mm though. See the small gap

at the top underneath the top clamping block in Fig. 2 for an example. Also see the exploded

view in Fig. 1 to realize by how much the top and bottom ribs extend the feathered ends of

the C ribs at this point to get an idea how long you should cut them before bending.

Bending the ribs

For the bending itself the same rules as for the C ribs apply. If you need bending tips, check

the chapter Bending the C ribs

.

1. Screw the four screws again in the mould again so that they rise the corner blocks about

1.5-2 mm above the surface of your workbench. Again try to put the rib stock right next

to the cor

ner blocks checking that it overlaps the corner blocks by 2 mm at the bottom

and 2+ mm at the top.

2. Cut the ribstock to correct lengths and decide the orientation of each piece, depending on

the flame. W

ith the bottom ribs, if the flame is slanted, you need to make them in two

pieces to match the slant of the rest of the ribs on both sides {mirroring}.

3. Bend the ribs. Again, for bending tips, see Bending the C ribs

.

4. Let dry.

The bottom seam

If you chose to mak

e the bottom ribs in two parts, before gluing, you will need to make them

fit as perfectly as possible. The seam must be at right angle to the bottom plane and must be

aligned with the centerline of the violin.

1

. Let the ribs be clamped at the lower corner blocks (B1

and C1) and mark the center plus 1

mm at each of the two ribs.

If you have a perfectly flat surface to rest the mould on, use a square to mark the lines

wher

e the ribs will be trimmed.

2. Trim the ribs and check how the ends align with each other. The goal is to make a seam

that is bar

ely visible. To make adjustments, you can use a small shooting board and a

block plane, your knife or a flat file.

3. Keep aligning until the ends meet well.

The clamping

F

or the whole job you will need 6 C-clamps in positions marked in red, see Fig. 2 .

1

. Notice the 6 clamping blocks "A1, B1, C1 and A2, B2, C2" in Fig. 1 which ar

e made of

hard wood with the sides touching the ribs following the curvature as closely as possible.

Also, the sides touching the ribs are padded with something soft {ie. leather} to ensure

the best contact possible without harming the ribs.

2. Again, as with the C ribs, the red arrows in Fig. 2 denote wher

e the clamps` action should

be. Before gluing, try to clamp down the ribs in their final positions to ensure that

everything sits well and that there are no gaps anywhere.

Gluing the bottom ribs

1. Optionally, preheat the block you are about to glue to get more working time.

2. Put some medium thickness glue on the bottom block "A1" , align the lef

t rib with the

violin center and hold down with your thumb. Take the right rib along with the clamping

block, position quickly to create the perfect seam, hold with both your thumbs for about 10

seconds, slide the clamping block in position and clamp down. Check that the ribs still

match perfectly and that they stand firmly on the workbench overreaching "A1" block on

both sides by at least 1-2 mm .

3

. The same goes for the "B1, C1" cor

ner blocks. Put some glue on the "B1" cornerblock and

running your fingers from the already glued "A1" block up to the "B1" block make sure

there are no gaps between the ribs and the mould and that the rib rests on the workbench.

Clamp swiftly.

4. Repeat with the "C1" block.

Gluing the top ribs

1. Here you can start the gluing from the upper corner blocks "B2"

and "C2" going up to the

top "A2" block. The procedure is otherwise the same as with the bottom ribs.

Category: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Gluing the top and bottom ribs

1

A B

C D

2

D

MakingTheViolin.com

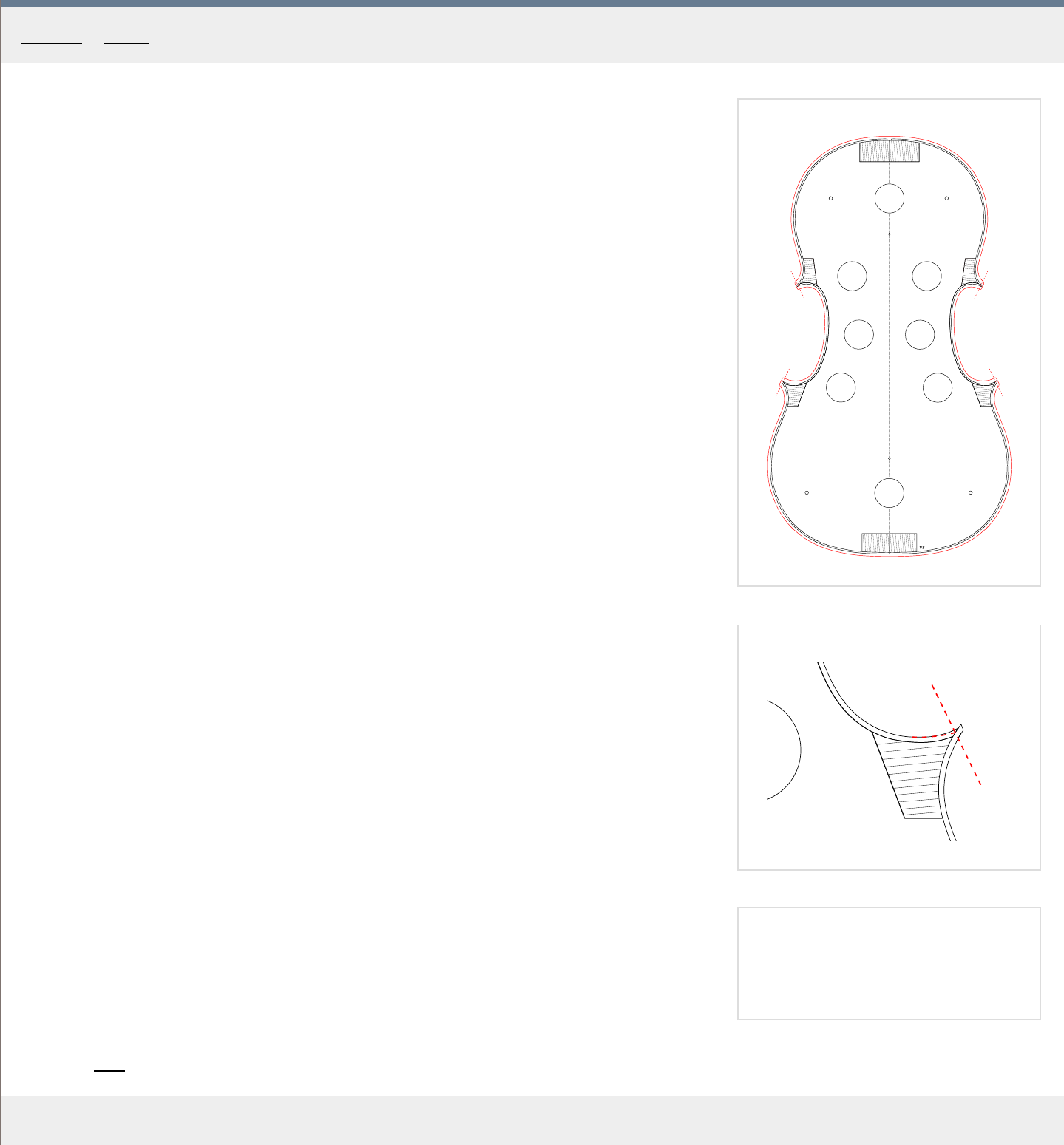

Finishing the corners

1

. Remove the four screws from the mould again.

2. Plane down the heights of all the ribs on both sides, leaving them just a little proud (.5

mm) of the blocks. When planing, follow the outline of the ribs with your block plane to get

a smooth cut.

3. Measure the span of the upper "A-B"

and lower "C-D" corners and compare it to the

original violin. If you have got the original plate outline printed out you can also now try to

align the ribs over it and check this way how close you are to the original. See the red

plate outline in Fig. 1.

The final ends should ideally be where the feathered C bouts end.

4

. Determine where the final tips should be and mark them at the top of the ribs. See the red

dashed lines in Fig. 1.

5. Using your razor sharp knife, trim the upper and lower ribs` protruding ends so that they

e

xtend beyond the previously made marks by about 1 mm . See Fig. 1. Be very careful

not to chip the ends - when you are getting near the end of the cut, stop and finish the cut

from the opposite direction.

6. If the final ends don't coincide with the feathering, see the paragraph below for possible

solutions.

7. Make the ends of the ribs flush with the feathering using an abrasive paper block. Make

sur

e the tips are at right angles to your flat surface (workbench).

8. Use the sanding pager of your flat surface to make the ribs level with the blocks, on both

sides. Y

ou should still be left with the rib height a little (.5 mm) higher than the final

heights.

In case you're a little off

If the tips of your ribs are still too wide and you have already reached the feathering, you can

still reduce their width but the thickness of the C bouts at their feathered ends will also have

to be reduced, because at the very ends of the corners, the thickness must still remain that of

the ribs, which is about 1.1 mm, not more. In Fig. 2. you see this done for the lower right

corner "D" . The red dashed lines denote the material removed.

If, on the other hand, the feathering is inset too much and it doesn't reach your projected tips,

you will need to shorten the tips further to reach that feathering even if it means the resulting

violin will be a little narrower at the corners.

Category: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Finishing the corners

1

2

3

MakingTheViolin.com

Creating the strips

1

. Create spruce or willow strips 7 x 2 mm

, ideally about 40 cm long. The wood grain should

run parallel with the length. Both horizontal and vertical grain can be used.

To thickness the strips, use your regular blade block plane, clamping down the one end of

the strip to your workbench. See the Thicknessing section in

Preparing the ribs for

thicknessing tips.

Make sure the thickness of 2 mm is maintained all over the strip, as thick

er strips are

difficult to bend and thinner aren't firm enough.

Cutting the mortices

The mortices are to be cut 2 x 7 x 7 mm into the top, bottom and C bout side blocks. For

this, use a sharp knife and also preferably a 1.5 mm wide chisel. Notice that the mortices are

cut for the C linings only, see Fig. 1.

1

. Mark the 7 mm length and 7 mm depth lightly on the blocks using a compass.

2. Cut the wall of the mortice opposed to the one adjacent to the rib to about 3.5 mm depth,

using your knife.

3. Cut the end wall of the mortice using your narrow chisel.

4. Cut the bottom of the mortice using your narrow chisel and scoop out the material.

5. Cut the wall again to the final 7 mm depth.

6. Cut the end wall of the mortice using your narrow chisel, finishing it.

7. Cut the bottom of the mortice using your narrow chisel, scoop out the material and finalize

the mortice.

8. Repeat with the remaining C blocks and on the other side.

Bending, fitting & gluing

1. Bend the strips on your bending iron as you would the ribs and cut them to required

lengths. If the outline of the ribs is perfect, the linings should be a perfect fit, no gaps

whatsoever should be pr

esent. Any gap will tend to alter the rib outline quite significantly.

This can be used to your advantage, if the outline of the ribs needs corr

ecting. Leave a

small gap where the ribs need to be less curved, clamp with your fingers and see how it

affects the outline. See Fig. 2. for correctly fitted linings, here in red.

1. After you have fitted all the linings, clamp them using rubber band reinforced clothespins

and let dry. Take a look at Fig. 3. to get an idea of the distribution of the clothespins.

Gluing

1. Work in parts, remove the clothespins holding one lining.

2. Preheat the part to get longer working times.

3. Apply medium thickness glue to just the lining. In case of C linings apply also some glue in

the mortices.

4. Put the lining in, make sure it is perfectly flush with the ribs and reclamp with the

clothespins as quickly as possible. Again, mak

e sure the lining remains flush with the ribs.

Category: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Linings

1

2

3

MakingTheViolin.com

Finishing the rib structure

1

. When the linings have dried, sand the whole rib structure down on both sides to the final

heights, ie. 32 mm at the bottom and 30 mm at the top /Messiah/.

2. Glue size the ends of all blocks with thin hide glue.

3. Finish the corners up to the tips using a fine file and sandpaper on a stick.

The rib structure is almost finished. F

or now , you should leave it on the mould to

prevent warping. The remaining steps in this chapter are carried out after the top

and back plates have been finished. If you are ready to start on the front plate,

refer to the next chapter called Front

.

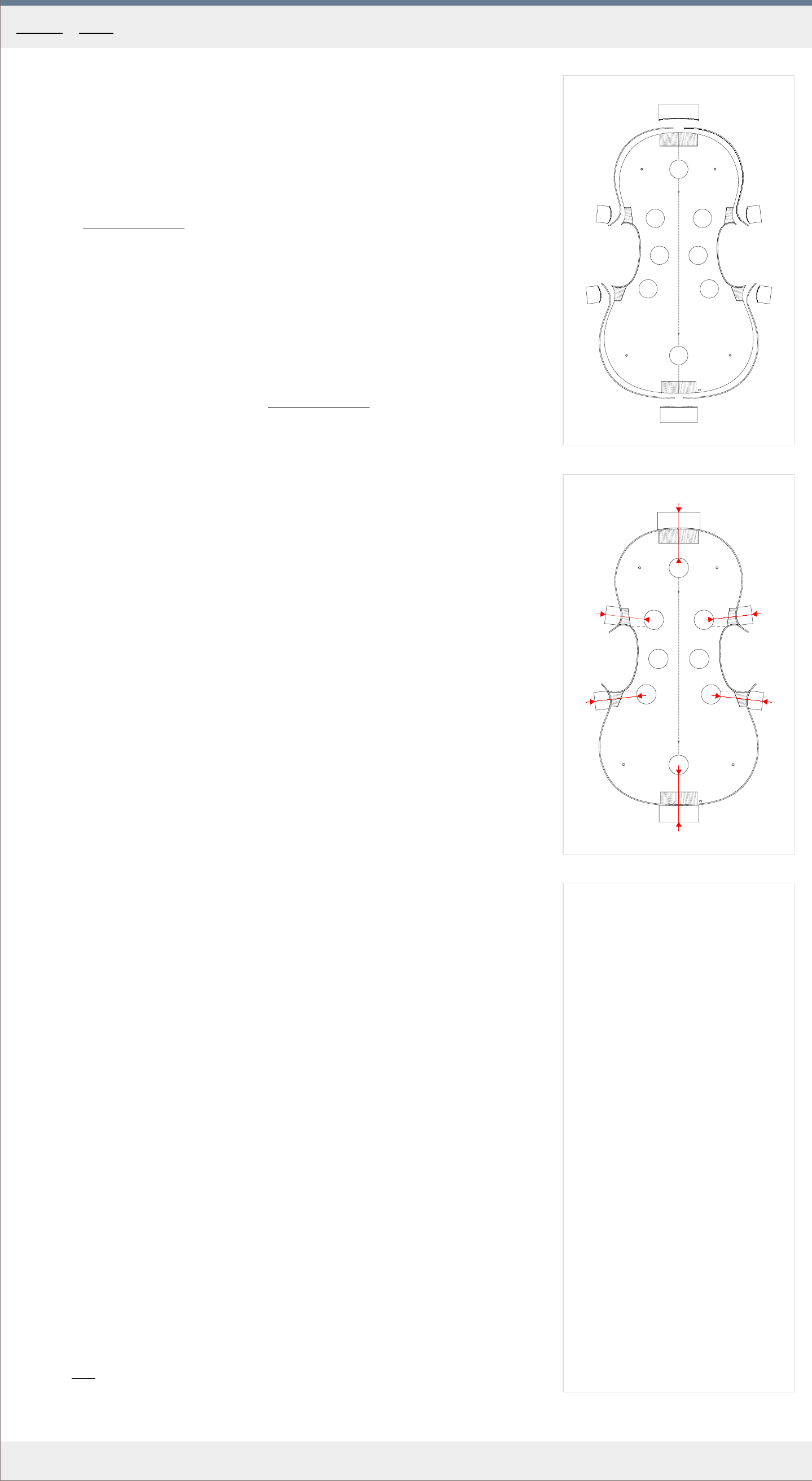

Removing the ribs from the mould

1. Mark distinctly the top of the rib structure, so that later you are able to tell the top-bottom

orientation.

2. To snap the blocks free of the mould, put your fingers where the red ellipses are in Fig. 1.

to serve as a kind of safety bed and tap lightly with a small hammer on the opposite side,

on the block, see r

ed arrows in Fig. 1 .

3. Repeat with other blocks, until the whole rib structure is unglued.

4. To slide the ribs off the mould, hold the ribs in the waist and spread them so that the upper

and lower cor

ner blocks are completely outside their mortices, resting on the edges, see

the red arrows pointing to those places in Fig. 2 . Of course, you need to be careful not to

break the rather fragile structure, the top and bottom spruce blocks are sometimes also

prone to splitting.

5

. Now you should be able to remove the ribs from the mould starting with the bottom block,

working your way up.

6. Inspect and carefully remove any excess of glue. Check the ribs for any missing

parts/splinters that may have br

oken off/gotten stuck to the mould. Reglue if necessary.

Trimming the blocks

1. Put the ribs on a flat surface and take a look at the shapes of the top and bottom blocks in

Fig. 3. . If you want, you can mark the r

ound outlines to guide your cutting.

2. Using a sharp chisel trim the top and bottom blocks. Work gradually, the first cut being

always small to r

ead the splitting angle, to allow for corrections in case the wood splits

unevenly a make sure the newly created walls are perfectly perpendicular.

The final thickness of the top block "a" is 18 mm , and of the bottom block "b" is 16 mm .

3. Use a shallow gouge for the cornerblocks.

See Fig. 3. for how the finalized blocks should look lik

e.

4. Inspect the blocks again making sure there are no splinters or loose parts that might cause

buzzes later on. F

inish with sanding paper, if you wish.

Shaping the linings

1. Take a pencil and draw a guiding line in the middle of each lining along their length.

2. With a suitable sharp knife start cutting the lower half of each lining leaving the bottom

about 0.5 mm thick. See the "1" pr

ofile in Fig 3. for reference.

3. Smooth the resulting "hump" with a scraper to create a good beveled surface as in "2" .

F

inish with sanding paper, if you wish.

You should inspect the whole structure again to see there are no loose pieces of wood or

splinters which might later cause buzzes in the finished instrument. Also check that

everything is glued together and that there are no gaps.

If you need to store the ribs elsewhere, put it somewhere with constant humidity, preferably

about 50 percent, and room temperature.

The weight of the finished ribs should be about 50 grams .

Category: Ribs

Home - Ribs - Finishing the rib structure

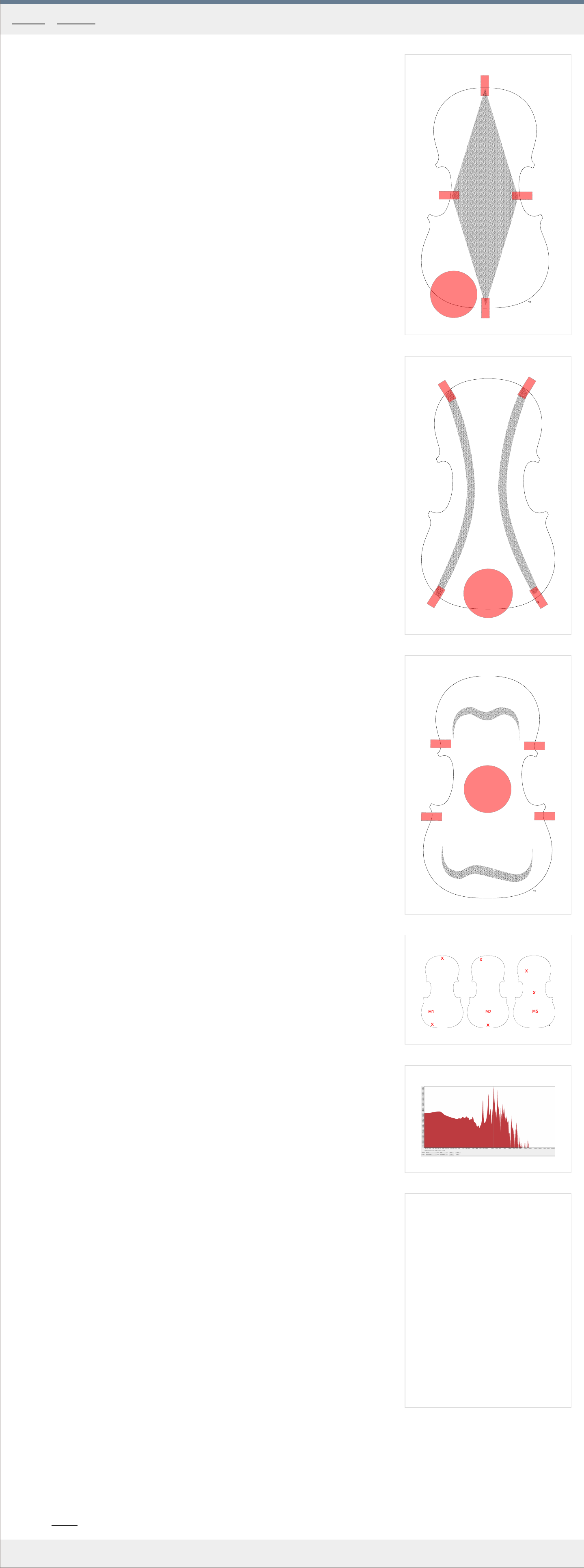

a

d

c

Front

MakingTheViolin.com

Home - F ront

1. Preparing the wood for the front plate

2. Marking the front plate outline

3. Shaping the plate corners

4. Sawing the front plate outline

5. Finalizing the edge thicknesses and creating the platform

6. Marking and cutting the purfling channel

7. Bending and gluing the purfling

8. Arching

9. Marking and fluting the F-holes

10. Hollowing and thicknessing

11. Cutting the F-holes

12. Bass bar

1

A

B

C

D

2

3

A B

4

A

B

5

6

C

7

8

MakingTheViolin.com

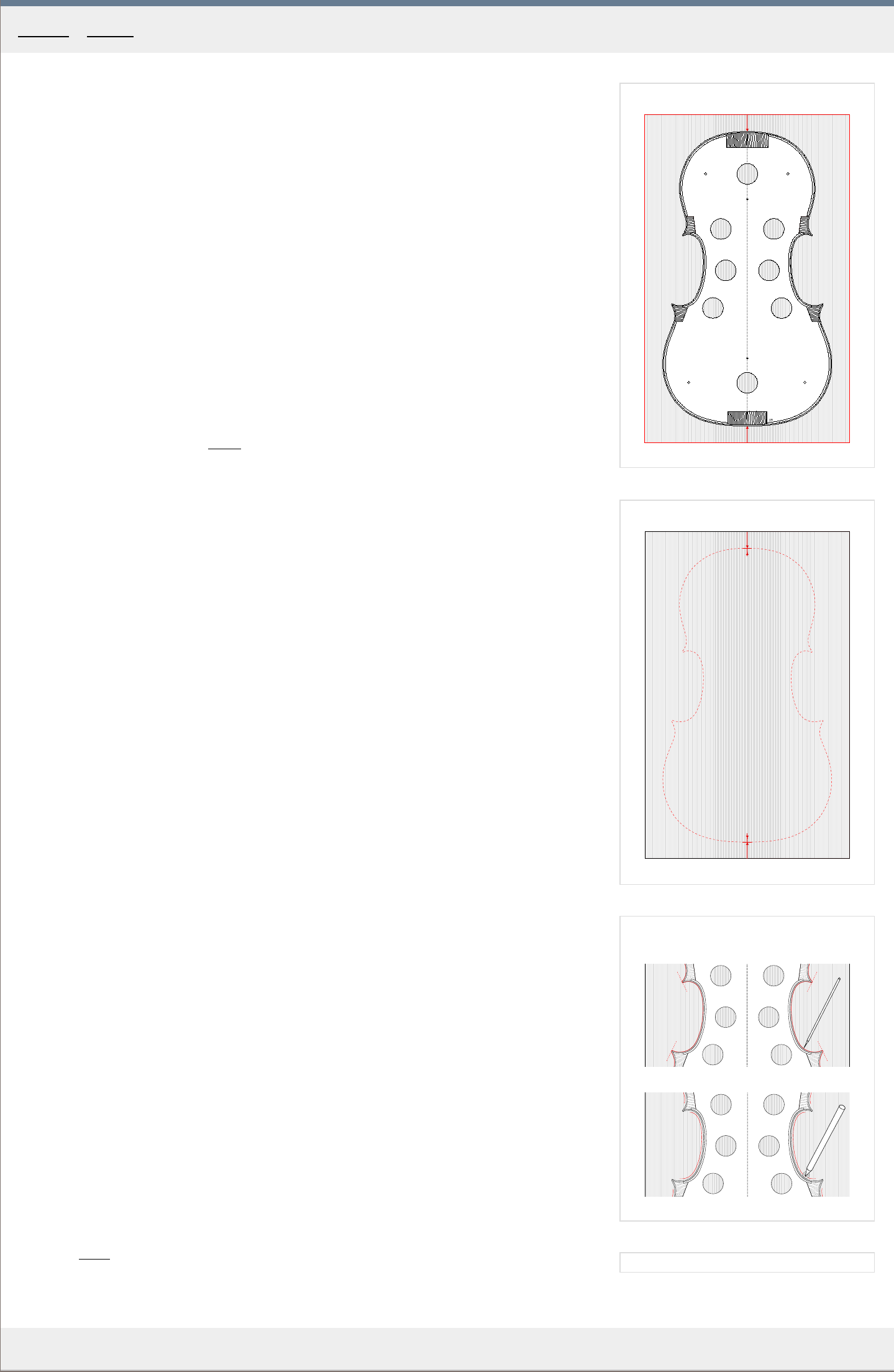

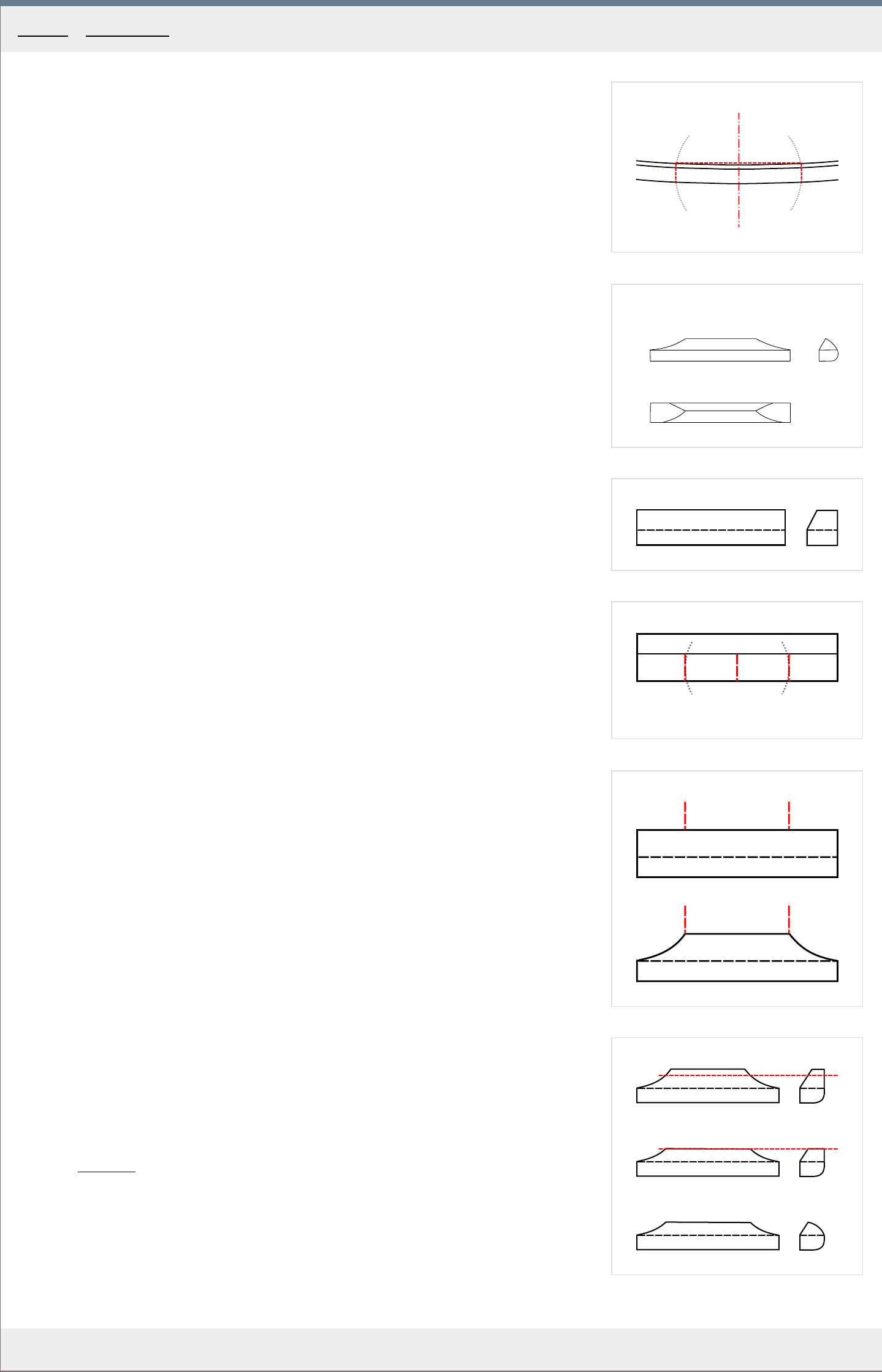

Choosing the wood

The wood for the front plate should be as flawless as possible.

1

. Check that the wooden billets have sufficient dimensions for the violin you are building.

2. Check for the following errors: Fig. 1. , points "A-C" for possible er

rors.

a) In point "A" you see an assortment of twists and warps as well as a r

esin streak.

b)In "B"

the growth lines are straight but the gluing surfaces have to be planed to make

the lines parallel with them.

c) In "C" you see the staining caused in most cases by o

xidation. You may or may not be

able to planed it off depending on location and size.

d)

In "D" everything is cor

rect.

3. See that the billets are correctly quartersawn, which means that the growth lines should

look lik

e in Fig. 2. when looked at from the side. (sometimes the cutting marks from the

circular saw may interfere with the reading of the growth rings. Shave off the marks with

you block plane to get a clear view of the rings) Making sure the wood is correctly

quartered is especially important if you get the wood in precut billets where any

corrections are almost impossible. Badly quartersawn wood with growth lines not going at

right angle to the bottom plane is structurally much less stable.

4

. The runout is a deficiency in wood which is one of the most difficult to indicate. It happens

when the cut of the wood is not in perfect alignment with the natural run of the grain. That

is why the best wood with no runout should always be split rather than cut. See Fig. 3 for

illustration. The r

ed planes depict the natural grain. In "A" the natural grain is misaligned

with the billet, indicating that there is a runout. If there is no runout, the billet should split

through its center, along the red plane as in "B" . A little runout is usually not a problem,

but more of it may negatively affect the structural integrity of the wood.

5

. If you want, you can also check the growth line density. It can vary throughout the piece.

Some gr

eat violins have it ranging from medium {1-1.5mm distance} at the edges of the

plate to dense {0.5 mm} at the center. Dense growth lines all over usually mean denser

wood which you should probably avoid. Look at the growth lines in the wood of the violin

you are copying and try to find similar wood if you are aiming for similar sound.

It is also helpful to make a note of the specific gravity of the pieces you chose and better yet,

make a table which will list the parameters of the woods used as you progress from one violin

to the next for reference. Check the Specific gravity calculator in the Materials

section. You

can create a table like this one:

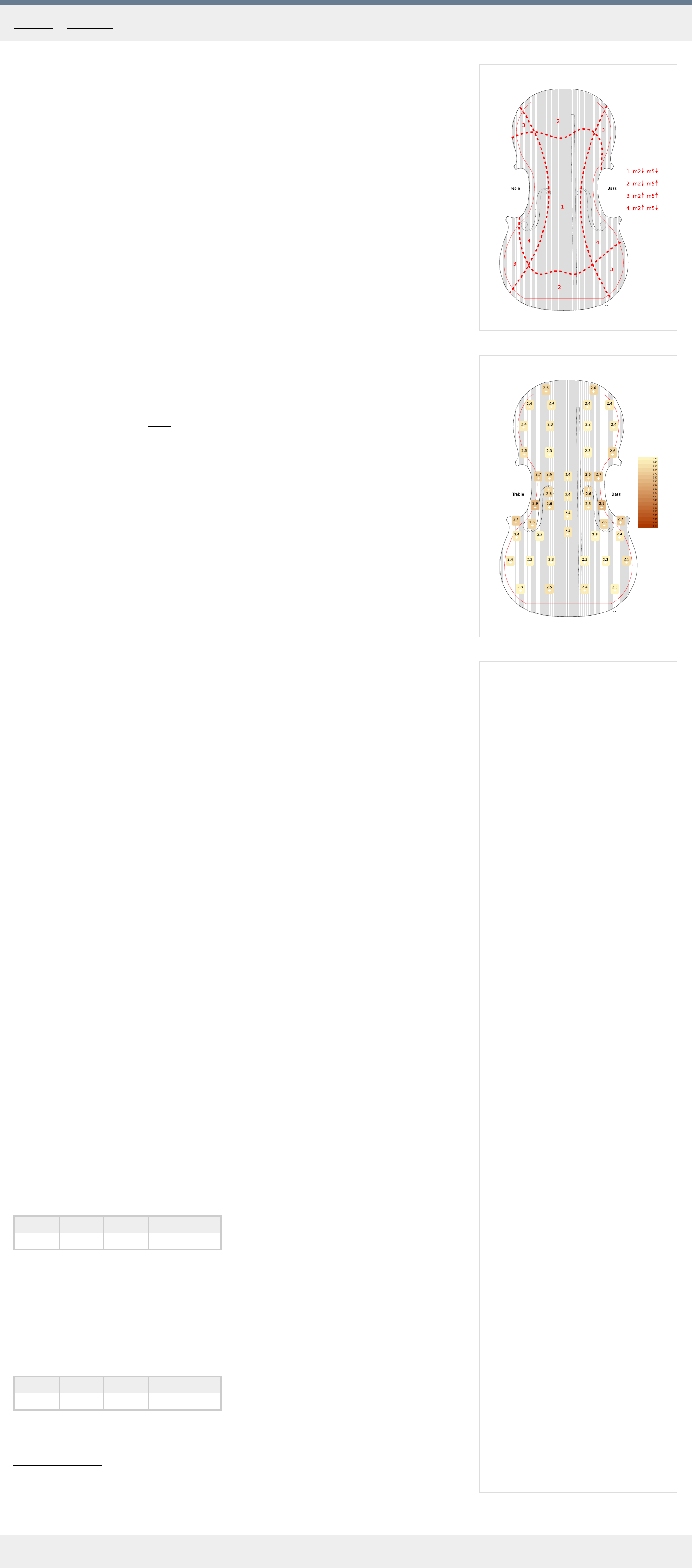

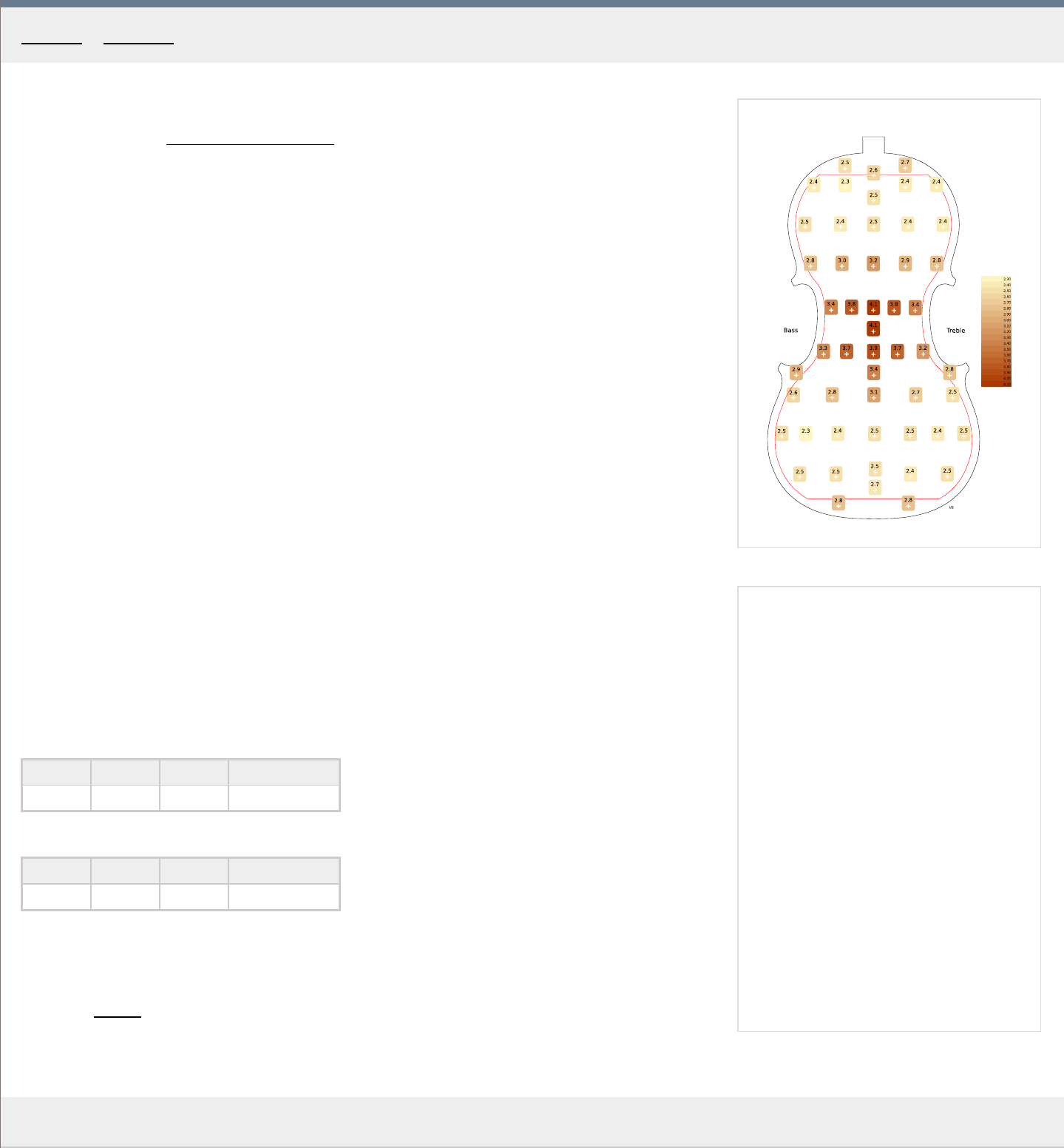

Violin no. Wood Source Date Specific gravity

1 Spruce Andreas Pahler 2003 0.41

Numbers around .42 for spruce and 0.55 for maple are considered good.

Preparing the wood

If you decide to cut the bass bar from one of the halves before joining them together,

refer to the chapter on the Bass bar

for the dimensions.

1. Plane the chosen pieces flat on the bottom side, check for rock on your flat workbench.

2. Put the pieces together and plane the upper tops to see clearly where they meet. Be

car

eful not to remove too much wood as at the top the plates should still be thick enough

to accommodate the height of the finished plate. See next Fig. 4. Make sure that the

pieces put together have sufficient height both at the sides and at the projected center

joint. The violin we are building here has the finished belly height of about 16 mm, so with

a safety margin, the pieces should be about at least 20 mm high.

3

. Plane the sides at right angles to the bottom surface using preferably a jointer plane {no.

6 plane}. T

o do that, clamp one end of the piece in the vice and support the other with a

block of wood to make sure the piece won`t bend while planing. See Fig. 5.

Check the edges with a square. Both edges must be at right angles to the bottom surface

along the whole length. No twist.

4

. Make sure the growth lines run parallel at the center. Make any corrections now, before

you finalize the joint in the ne

xt step.

5. Bring the two edges together and check for gaps and rock. Use a source of light positioned

behind the joint to see how the surfaces match up. If the surface is a little convex

(lengthwise), push down during planing a little mor

e at the center to correct that. Special

attention should be paid to the extremes, which should be in perfect contact up to the

ends.

6

. Optional: Put your sash clamps in place and test clamping down the billets. The join

surfaces must be in perfect contact, with no visible gap, when the billets are fully clamped.

If they ar

en't its either you didn't prepare them well enough or the action of the clamps

may be wrong. In that case, try to correct (by planing) the outer sides of the billets (those

which run parallel with the gluing surfaces), to compensate.

7. Lastly, before gluing, make two vertical marks on both pieces, crossing the joint, using a

pencil. This will help you cor

rectly align the top piece quickly and precisely when the glue

starts "biting". See the two short horizontal lines in Fig. 6.

Because the wood tends to "move" with the changing humidity and temperature in your

workshop, it is recommended to glue the pieces together right after you have achieved a

good fit.

Gluing the pieces together

1

. Put one piece in the vice with its gluing surface up. See Fig. 7.

Y

ou should rise the temperature in your workshop or use a heater to heat up the pieces, to

prolong the working time of the glue. Do not heat up the pieces too much or unevenly, as

that will cause the glue to penetrate the wooden surfaces unevenly, with very high

penetration in hot areas, resulting in a starved joint. So a joint that has 30C evenly

distributed is ideal.

2

. Using a larger brush, apply ample medium thickness hide glue all over the gluing surface

on both the clamped piece and the other one (you ar

e holding in your other hand) as fast

as possible.

3. Put the gluing surfaces together and rub vigorously back and forth, while still maintaining

full contact of the surfaces, pr

essing down, squeezing out the glue. See Fig. 7.

4. When you feel the glue starts "biting", finish the move and align the surfaces as precisely

as possible (mak

e the previously made marks meet).

5. Optional: Let dry for 30 seconds, then carefully lay down on the prepared sash clamps and

clamp down lightly as in Fig. 8.

6. Clean up and let dry over night.

Category

: Front

Home - F ront - Preparing the wood for the front plate

1

A

B

x2

x1

2

A

B

x2

x1

3

A

B

MakingTheViolin.com

After the plate had dried, check the bottom side with your straightedge. If the bottom is

uneven, you will have to plane it perfectly flat so that the ribs are in full contact with it.

1

. Remove all excess glue and clamp the plate down on your workbench. If you have a

workbench with dogs, use those to fix the plate upside down. Or you can use sash clamps

to hold the plate and clamp the sash clamps down to your workbench.

2. Make the bottom perfectly flat using your long plane. Be careful of the wood grain. The two

billets' grain runs in opposite dir

ections so you will need to keep flipping the plate

frequently to go with the grain to avoid tearing. The tearing is more likely with highly

flamed maple. Tilting the plane sideways a little or going accross the grain should help too.

If nothing helps, use the scraper blade.

3. To remove little tearing caused by planing and achieve perfect flatness, you can sand the

bottom on your flat sandpaper glass surface (you used this to finalize the rib height).

Fixing the ribs to the plate

Now you need to fix the ribs to the plate in or

der to transfer the actual outline. If at this

point you are also transfering the outline to the back plate, do not forget to

include the button. See the Back

chapter for its dimensions.

1. On the ribs, remark the centerline, if necessary.

2. Take the ribs and put them on the front plate facing upside down. Align the centerline on

the ribs with that on the fr

ont plate. See Fig. 1.

3. Mark out the very top and bottom of the ribs, drawing a 1 cm long line, at the centerline of

the plate. See points "A and B" in Fig. 1.

4. Remove the ribs and on the centerline of the top plate, scribe another pair of marks, about

4 mm inwar

ds from the top and bottom marks "A and B" you have just made. See Fig. 2.

The red dashed line just shows for illustration where the ribs were placed.

5. At those two points, drill through two holes, 1.5 mm in diameter, at right angles to the

plate.

6. Put the ribs back on the front plate in exactly the same position as before {par. 2}, clamp

down sufficiently and drill two 5 mm deep holes into the top and bottom rib blocks using

the pr

eviously predrilled holes as guides.

7. You can now plug into the holes two 1.5 mm drill bits as locating pins to k

eep the ribs

positioned on the plate. With the bits in place, you can remove the clamps and start with

the outline.

Marking the outline

Make sure the outline of the ribs is flawless, the corners are finished.

1

. Using a sharp scribe, mark the whole outline of the ribs on the plate. Make sur

e you also

mark distinctly the ends of the ribs at the corners, but don't make the mark too deep as

this will stay on the finished plate. See "A" in Fig. 3.

2. Now you need to draw the second outline which will delimit the shape of the top plate and

which should be outset by about 2.5 mm fr

om the ribs, depending on the overhang on the

original violin. For this choose a washer, which you know will offset the contour by the

distance needed. Using a sharp pencil draw this parallel line around the ribs, but always

stop about 1 cm short of the tips of the corners. See "B" in Fig. 3.

Make sure you hold the pencil at a constant angle as different angles may produce

different distances. Make a couple of tests, to get the idea as to what kind of line the

washer and the pencil produce.

3

. Remove the locating pins and take the ribs off the plate.

Category

: Front

Home - F ront - Marking the front plate outline

1

x1

x2

MakingTheViolin.com

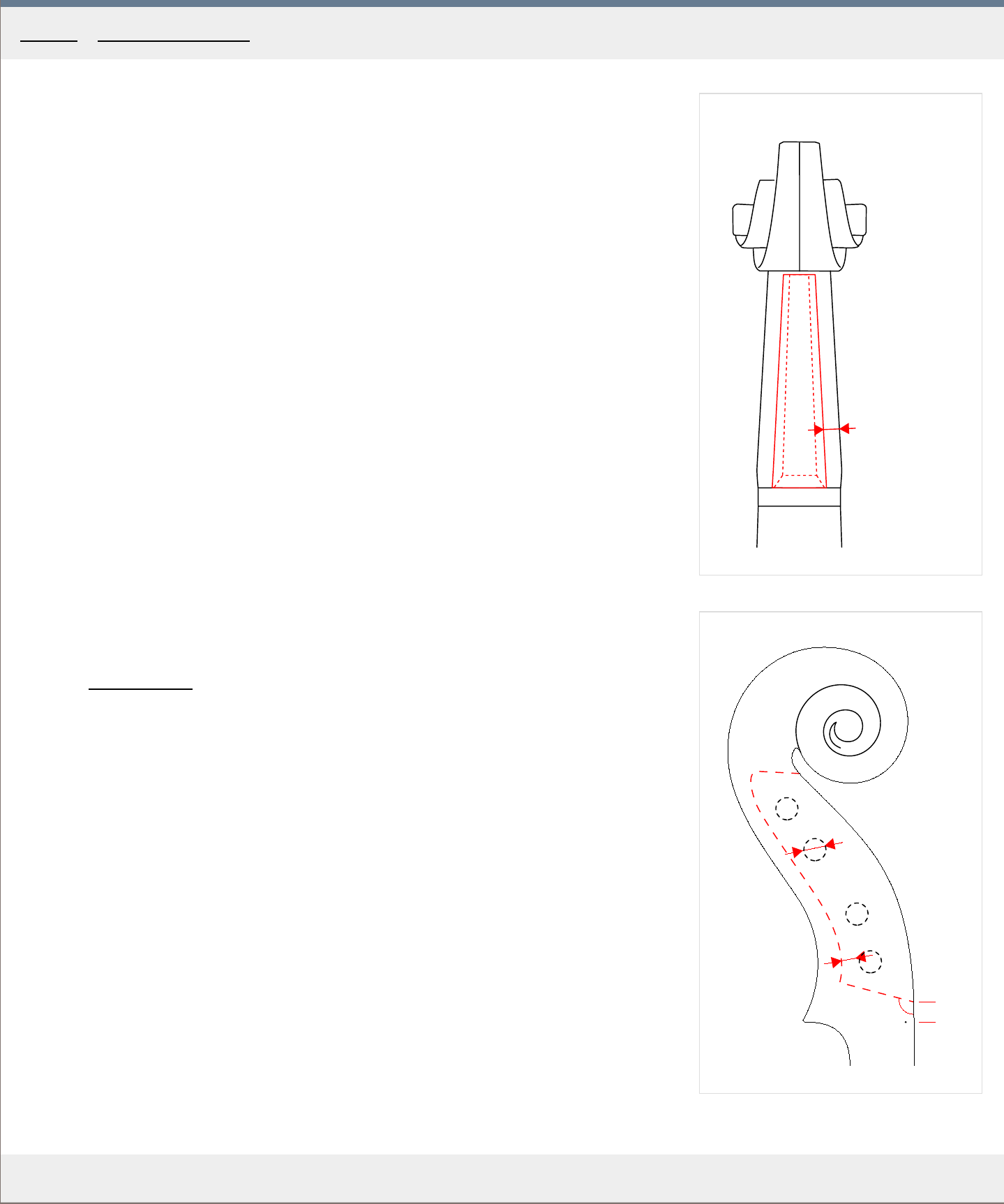

Shaping the corners

The shapes of the corners must now be reconstructed by hand. They are one of the focus

points on the violin and naturally they attract a lot of attention. Their proper execution is

therefore very important.

1

. It is helpful to construct for each corner a guideline by projecting the angle of the original

violin cor

ner`s tip towards the centerline at points X1 and X2. These points can then be

transferred to the new plate to help project the new corners. See the red dashed lines in

Fig. 1.

2. Mark the tips about 2 mm beyond the tip of the rib.

3. Finish the radii in accord with the original width and general shape of the corners.

Notice how the distance of the outline from the ribs increases especially with the wider

lower corners.

The newly created corners are depicted in solid red in Fig. 1.

Category

: Front

Home - F ront - Shaping the plate corners

1

2

A

B

D1

D2

3

A

B

C

D

v

v

MakingTheViolin.com

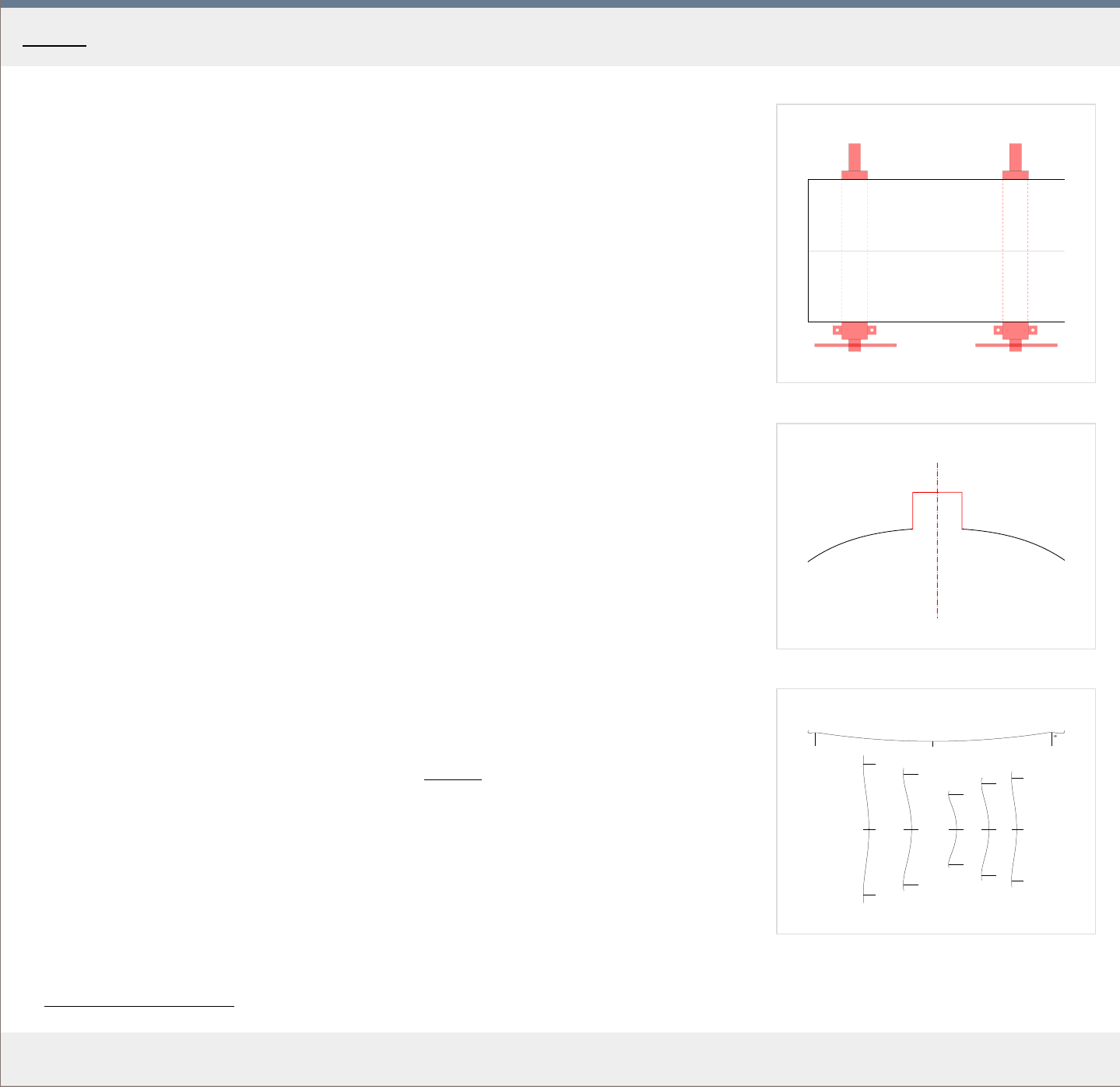

Fixing the plate

1

. Fix a wooden plank (in red in Fig. 1. ) of appr

oximately 60 x 7 x 5 cm to your workbench

making sure its protruding by at least 30 cm .

2. Clamp your front plate upside down to the bottom of this plank. See the top-down view of

the setup in Fig. 1.

Cutting the plate

1. Using a coping saw, cut within 2 mm of the outer pencil line. Mak

e sure the saw is tilted a

little away from the outline so that you avoid undercutting. Keep rotating the plate as

necessary.

2. Correct the outline using a rasp, downstrokes only, so as to avoid tearing off the fibers at

the bottom of the plate. Get to about .5 mm outside the outline.

3. Using a marking gauge, scribe along the whole length of the contour a line 6 mm in

height.

The plate holder

Now is the time to attach the plate to the plate holder

. It serves to hold the front and back

plate while you carve the outside arching and do the purfling.

1

. Get a piece of wood about 60 x 30 x 2 cm.

2. Mark the centerline, take the template you started the violin with and scribe the full violin

outline on the plate holder

.

3. On the centerline drill two holes about 12 cm in fr

om the top and bottom edges of the

outline. Refer to Fig. 2. for their position.

4. Find two screws and insert them in the holes from the bottom side to find out by how much

they pr

otrude. They must not stick out more than 8-9 mm but also not much less in order

to securely hold the plate. Use washers to reduce the length of the screws if necessary.

Fixing the plate to the plate holder

1

. Put the plate bottom down on the plate holder and align it with the centerline. Refer to

Fig. 2. to see how the plate is fix

ed to the holder.

2. Clamp down securely with a few clamps.

3. Flip the holder and screw in the two screws.

Make sure again that the screws will not enter the wood farther than 8-9 mm to avoid

penetrating into the wood that will be in the finished plate.

The holder must hold the plate firmly but avoid over-tightening.

4. Remove the clamps and clamp down the holder to the workbench.

Removing wood

1. With a pencil, mark out the outer "A

, B, C, D" areas as depicted in Fig. 3.

2. Using a suitable gougle, pare away the wood down to the 6 mm height-line, you

pr

eviously created. Make sure you do not "enter" the waist "v" of the plate more than 15

mm.

Take a look at the red arrows in Fig. 3 to see the general direction of carving.

As you continue removing wood be extremely careful in the area of corners, as these are

easily split off. Be e

xtra sensitive of the grain in those areas and apply only very limited

force. See the red arrows near the corner in Fig. 3 for the direction of carving. Also make

sure your gouge is razor sharp.

Category: Front

Home - F ront - Sawing the front plate outline

1

MakingTheViolin.com

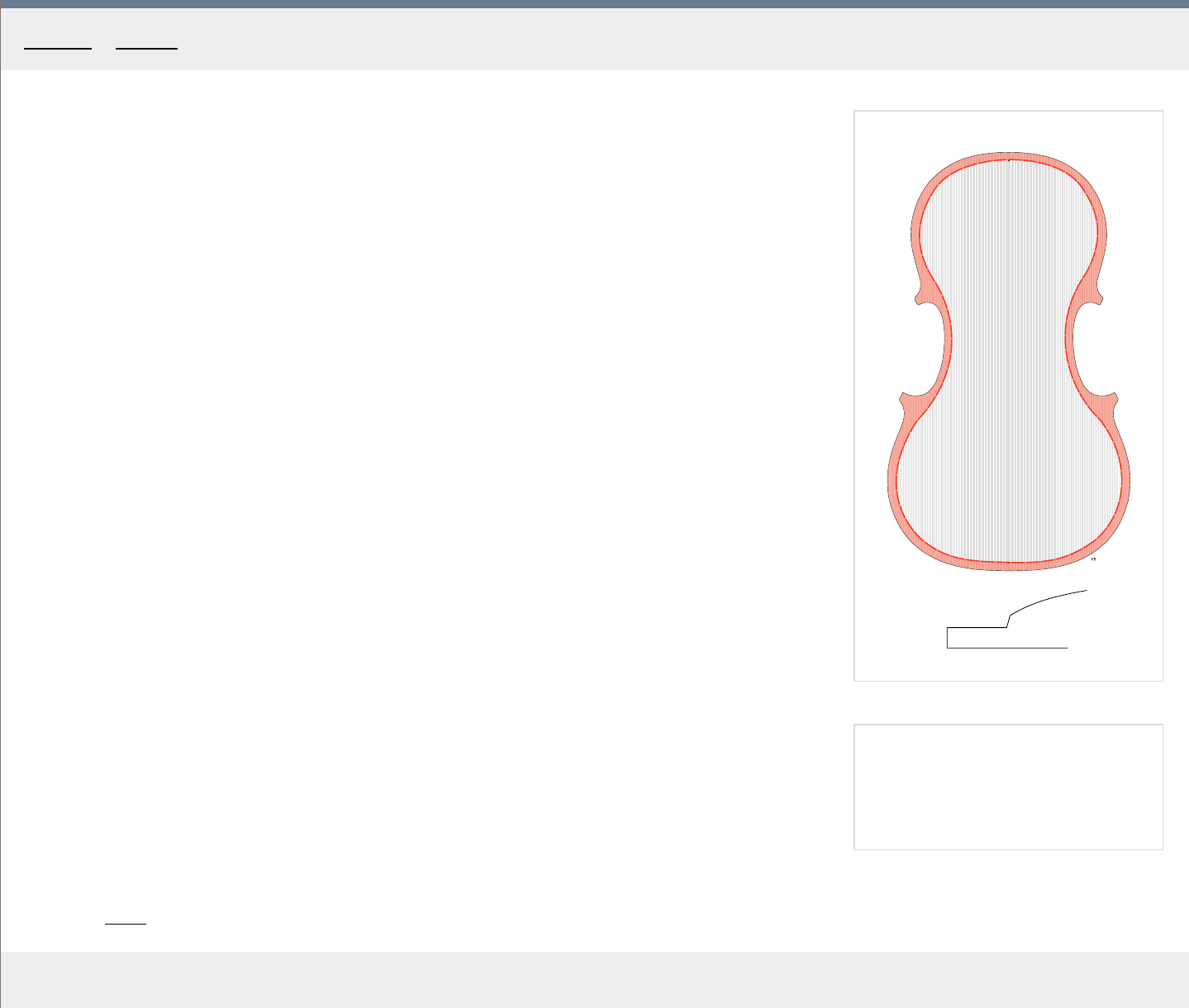

Finalizing the outline

1

. Now is the time to finalize the outline of the plate. Clamp upside down onto the plank as when

you wer

e cutting out the outline and using a file {downstrokes only}, make sure the outline is

even, smooth and true to the overhang, about 2.5 mm in our case. Leave the corners a little

wider than marked.

2. Again, using the marking gauge, mark the height, this time of 4.5 mm , all the way ar

ound the

plate.

3. Using a shallow gouge remove the wood along the edge farther down to the marked line. As

pr

eviously, be very careful in the area of corners. Always go with or across the grain, never

against. Refer to the Fig. 3. in the previous chapter for cutting directions.

4. According the Fig. 1 mark a line along the whole cir

cumference of the plate, see the red

dashed line, 7 mm in at the waist and 9 mm in at the upper and lower bouts. This line will

serve to limit the scope of the platform. The marking is best done with a compass, its needle

following the edge of the plate.

Creating the platform

1

. Using a narrow chisel, make a series of vertical incisions along the red dashed line in Fig. 1

not going too deep into the wood. Be car

eful in areas where the grain runs parallel to the

incisions allowing the gouge to enter the wood easily.