Handbook of Intelligence Studies

The Handbook of Intelligence Studies examines the central topics in the study of intelligence

organizations and activities. This volume opens with a look at how scholars approach this

particularly difficult field of study. It then defines and analyses the three major missions of

intelligence: collection-and-analysis; covert action; and counterintelligence. Within each of

these missions, some of the most prominent authors in the field dissect the so-called intelli-

gence cycle to reveal the challenges of gathering and assessing information from around the

world. Covert action, the most controversial intelligence activity, is explored in detail, with

special attention to the issue of military organizations moving into what was once primarily a

civilian responsibility. The contributions also cover the problems associated with protecting

secrets from foreign spies and terrorist organizations: the arcane but important mission of

counterintelligence. The book pays close attention to the question of intelligence account-

ability, that is, how a nation can protect its citizens against the possible abuse of power by its

own secret agencies – known as “oversight” in the English-speaking world.

The volume provides a comprehensive and up-to-date examination of the state of the field

and will constitute an invaluable source of information to professionals working in intelligence

and professors teaching intelligence courses, as well as to students and citizens who want to

know more about the hidden side of government and their nation’s secret foreign policies.

Loch K. Johnson is Regents Professor of Public and International Affairs at the University of

Georgia. His books include Secret Agencies (1996); Bombs, Bugs, Drugs, and Thugs (2000); Strategic

Intelligence (2004, co-edited with James J. Wirtz); Who’s Watching the Spies? (2005, co-authored

with Hans Born and Ian Leigh); American Foreign Policy (2005, co-authored with Daniel Papp

and John Endicott); and Seven Sins of American Foreign Policy (2007).

Handbook of

Intelligence Studies

Edited by

Loch K. Johnson

First published 2007

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Avenue, New York NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, an informa business

© Loch K

Johnson, selection and editorial matter; individual chapters, the contributors

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or

other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying

and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Handbook of intelligence studies / edited by Loch K. Johnson.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Intelligence—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Johnson, Loch K., 1942–

UB250.H35 2007

327.12—dc22

2006021368

ISBN10: 0–415–77050–5

ISBN13: 978–0–415–77050–7

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006.

“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s

collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.”

ISBN 0-203-08932-4 Master e-book ISBN

(Print Edition)

Contents

List of figures and tables viii

Notes on contributors ix

Glossary xiii

Introduction 1

Loch K. Johnson

Part 1: The study of intelligence

1 Sources and methods for the study of intelligence 17

Michael Warner

2 The American approach to intelligence studies 28

James J. Wirtz

3 The historiography of the FBI 39

Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones

4 Intelligence ethics: laying a foundation for the second oldest profession 52

Michael Andregg

Part 2: The evolution of modern intelligence

5 The accountability of security and intelligence agencies 67

Ian Leigh

6 “Knowing the self, knowing the other”: the comparative analysis of security

intelligence 82

Peter Gill

v

7 US patronage of German postwar intelligence 91

Wolfgang Krieger

Part 3: The intelligence cycle and the search for information: planning,

collecting, and processing

8 The technical collection of intelligence 105

Jeffrey T. Richelson

9 Human source intelligence 118

Frederick P. Hitz

10 Open source intelligence 129

Robert David Steele

11 Adapting intelligence to changing issues 148

Paul R. Pillar

12 The challenges of economic intelligence 163

Minh A. Luong

Part 4: The intelligence cycle and the crafting of intelligence reports:

analysis and dissemination

13 Strategic warning: intelligence support in a world of uncertainty and surprise 173

Jack Davis

14 Achieving all-source fusion in the Intelligence Community 189

Richard L. Russell

15 Adding value to the intelligence product 199

Stephen Marrin

16 Analysis for strategic intelligence 211

John Hollister Hedley

Part 5: Counterintelligence and covert action

17 Cold War intelligence defectors 229

Nigel West

18 Counterintelligence failures in the United States 237

Stan A. Taylor

19 Émigré intelligence reporting: sifting fact from fiction 253

Mark Stout

vi

CONTENTS

20 Linus Pauling: a case study in counterintelligence run amok 269

Kathryn S. Olmsted

21 The role of covert action 279

William J. Daugherty

22 The future of covert action 289

John Prados

PART 6: Intelligence accountability

23 Intelligence oversight in the UK: the case of Iraq 301

Mark Phythian

24 Intelligence accountability: challenges for parliaments and intelligence services 315

Hans Born and Thorsten Wetzling

25 Intelligence and the rise of judicial intervention 329

Fred F. Manget

26 A shock theory of congressional accountability for intelligence 343

Loch K. Johnson

Appendices 361

A The US Intelligence Community (IC), 2006 363

B Leadership of the US Intelligence Community (IC), 1947–2006 364

C The intelligence cycle 366

Select Bibliography 367

Index 371

vii

CONTENTS

Figures and Tables

Figures

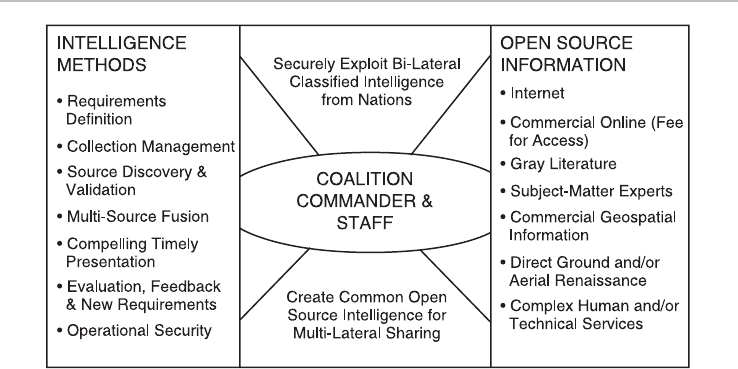

10.1 Relationship between open and classified information operations 131

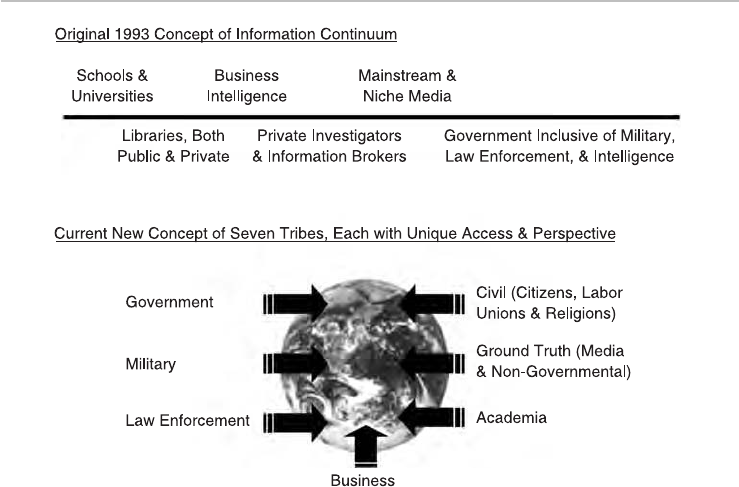

10.2 Information continuum and the Seven Tribes 132

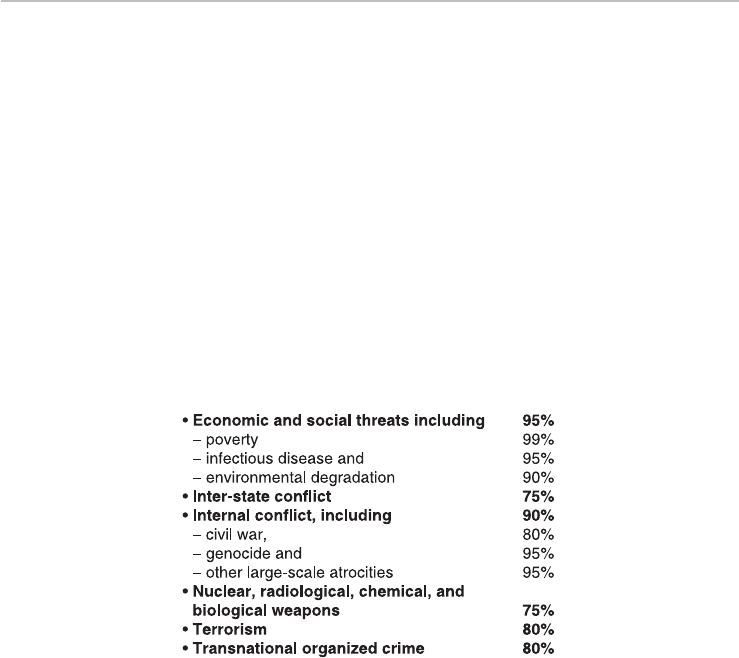

10.3 OSINT relevance to global security threats 134

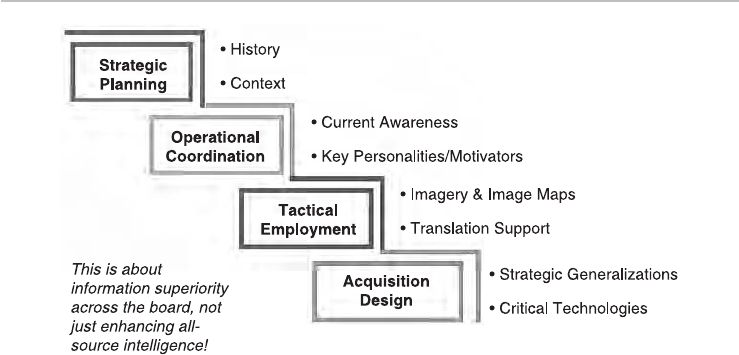

10.4 OSINT and the four levels of analysis 136

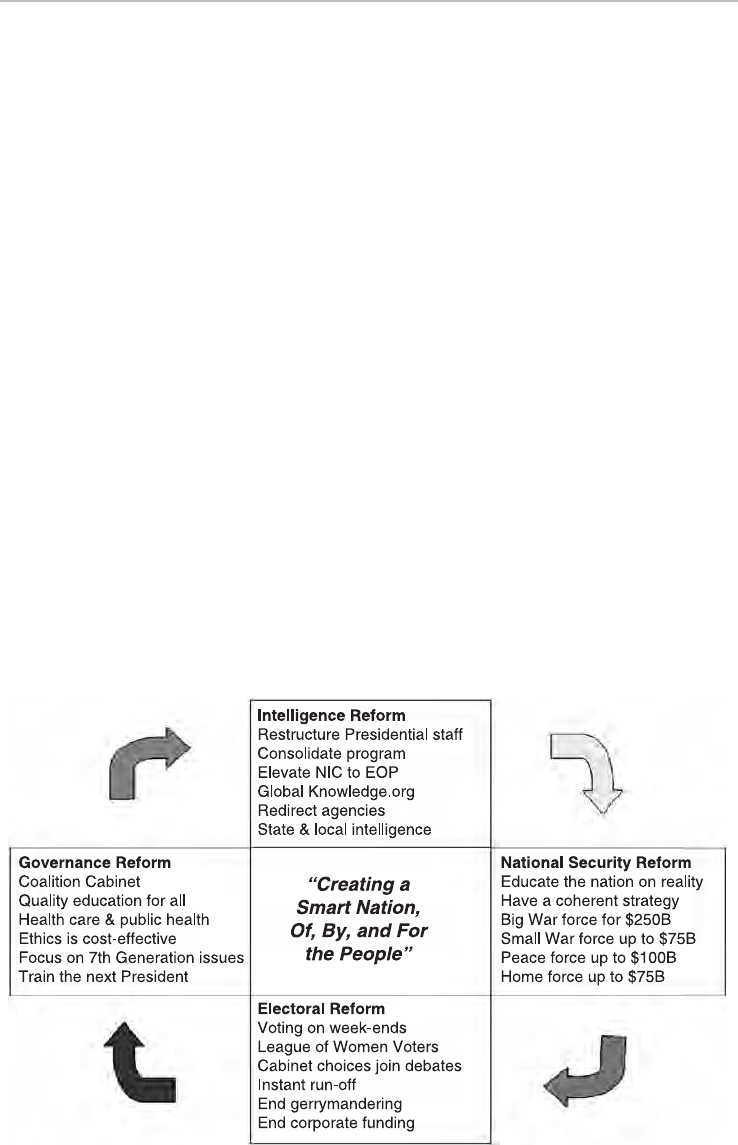

10.5 OSINT as a transformative catalyst for reform 137

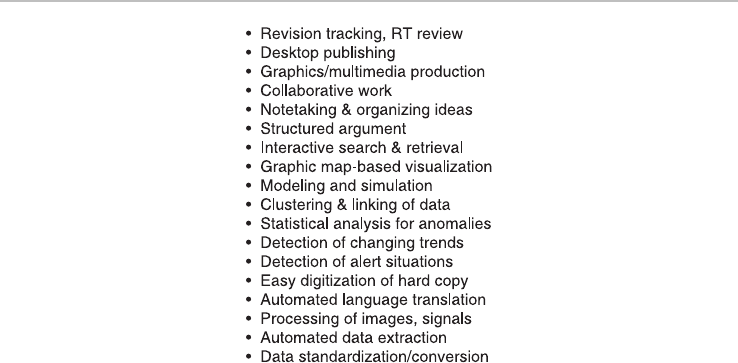

10.6 Fundamental functions for online analysis 139

10.7 World Brain operational planning group virtual private network 140

10.8 Standard OSINT cell 144

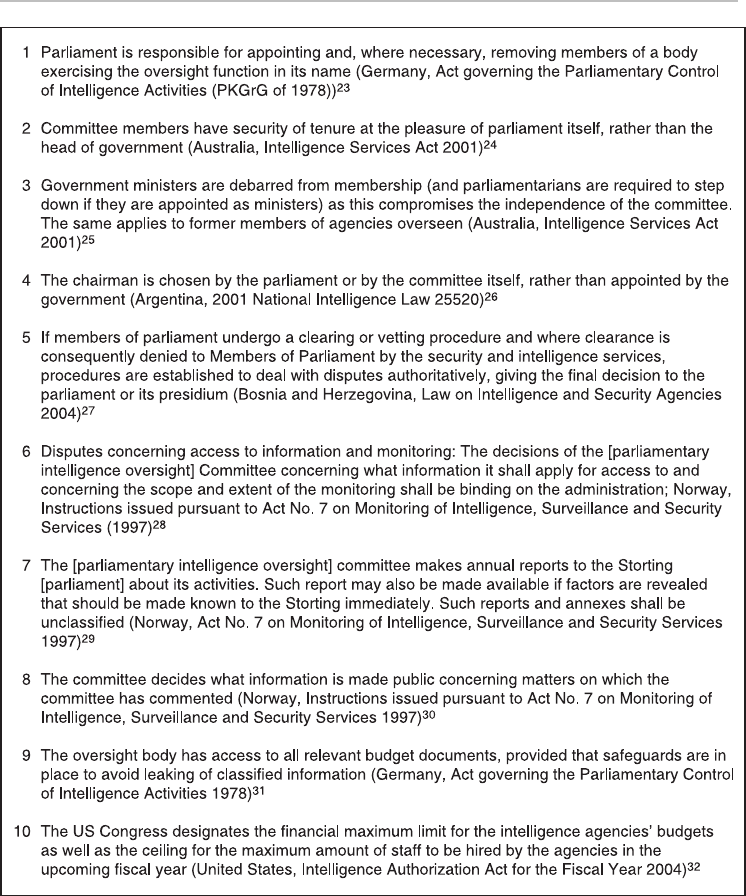

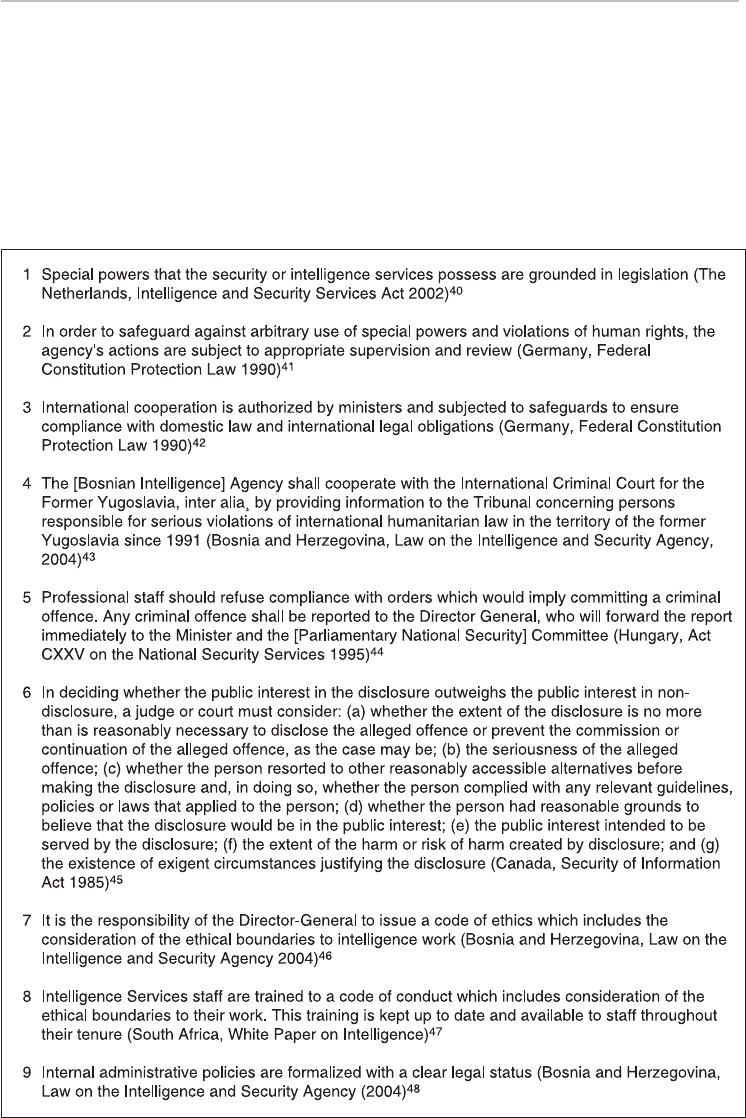

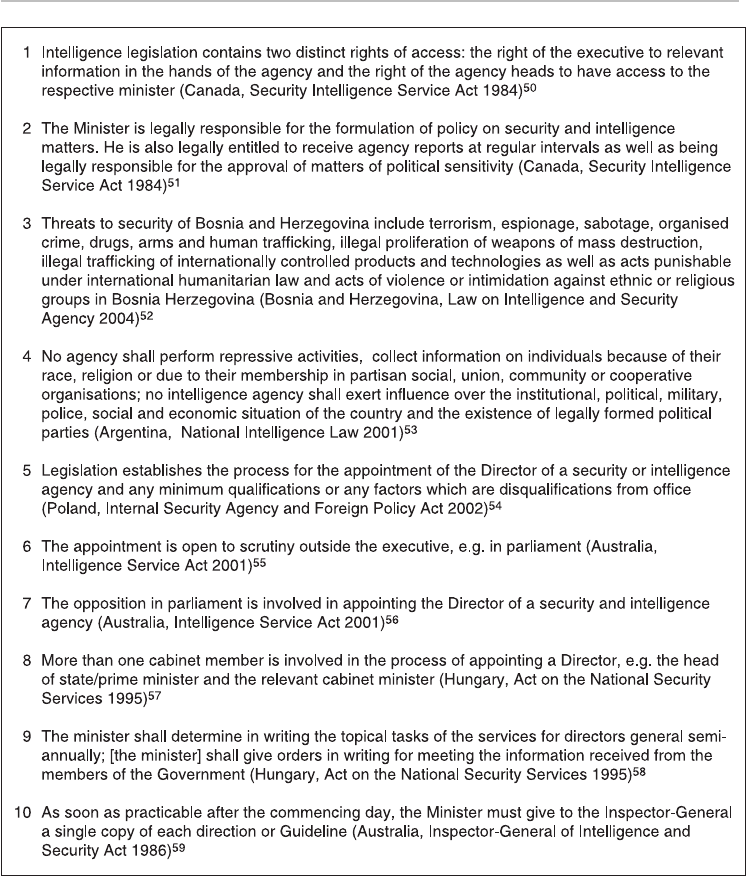

24.1 Best practice to ensure ownership over parliamentary intelligence oversight

procedures 319

24.2 Best practice aimed at creating “embedded human rights” 322

24.3 Best practice to ensure the political neutrality of the services 324

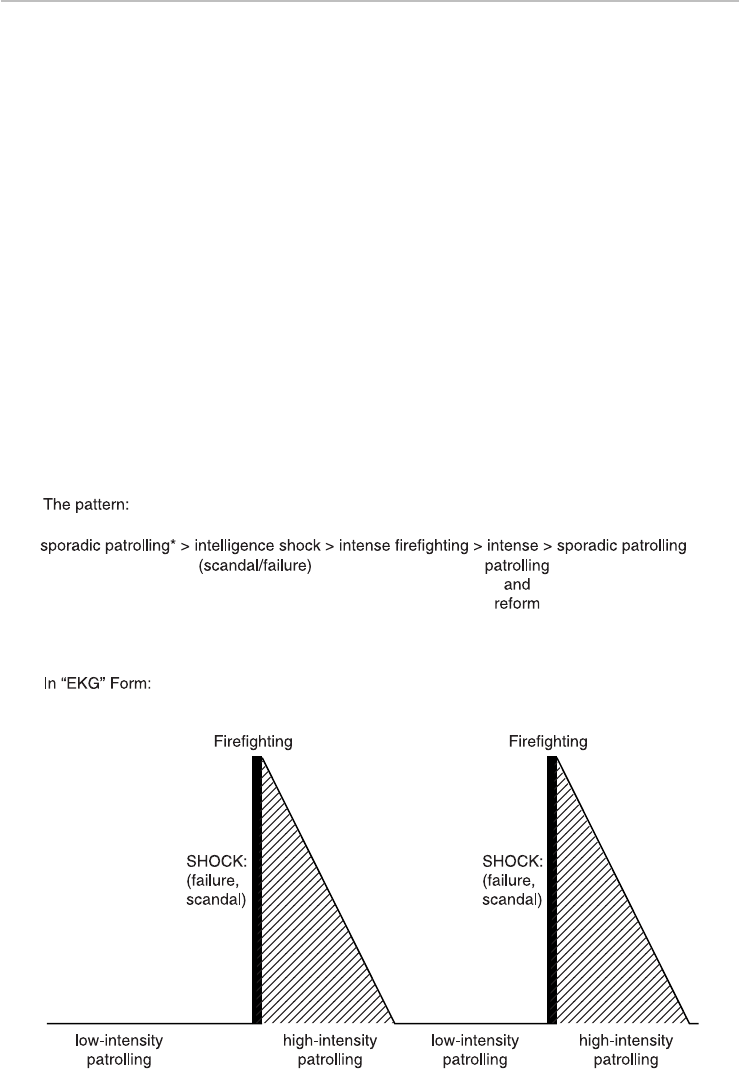

26.1 The dominant pattern of intelligence oversight by lawmakers, 1975–2006 344

Tables

6.1 A map for theorising and researching intelligence 87

18.1 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Court Surveillance Orders issued annually 248

26.1 Type of stimulus and intelligence oversight response by US lawmakers, 1975–2006 347

26.2 The frequency of low- and high-threshold intelligence alarms, 1941–2006 349

viii

Notes on Contributors

Michael Andregg is a professor at the University of St Thomas in St Paul, Minnesota.

Hans Born is a Senior Fellow in Democratic Governance of the Security Sector at the

Geneva Centre for Democratic Control of the Armed Forces (DCAF). He holds a Ph.D. and is

a guest lecturer on civil–military relations at the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in

Zurich and on governing nuclear weapons at the United Nations Disarmament Fellowship

Programme.

William J. Daugherty holds a Ph.D. in government from the Claremont Graduate School and

is Associate Professor of Government at Armstrong Atlantic State University in Savannah,

Georgia. A retired senior officer in the CIA, he is the author of In the Shadow of the Ayatollah:

A CIA Hostage in Iran (Annapolis, 2001) and Executive Secrets: Covert Action & the Presidency

(Kentucky, 2004).

Jack Davis served in the CIA from 1956 to 1990, as analyst and manager and teacher of

analysts. He now is an Independent Contractor with the Agency, specializing in analytic

methodology. He is a frequent contributor to the journal Studies in Intelligence.

Peter Gill is Professor of Politics and Security, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool,

United Kingdom. He is co-author of Introduction to Politics (1988, 2nd ed.) and Intelligence in an

Insecure World (2006). He is currently researching into the control and oversight of domestic

security in intelligence agencies.

John Hollister Hedley, during more than thirty years at CIA, edited the President’s Daily Brief,

briefed the PDB at the White House, served as Managing Editor of the National Intelligence

Daily, and was Chairman of CIA’s Publications Review Board. Now retired, Dr Hedley

has taught intelligence at Georgetown University and serves as a consultant to the National

Intelligence Council and the Center for the Study of Intelligence.

Frederick P. Hitz is a Lecturer (Diplomat in Residence) in Public and International Affairs,

Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University.

ix

Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones is Professor of American History at the University of Edinburgh. The

author of several books on intelligence history, he is currently completing a study of the FBI.

Loch K. Johnson is Regents Professor of Public and International Affairs at the University of

Georgia and author of several books and over 100 articles on US intelligence and national

security. His books include The Making of International Agreements (1984); A Season of Inquiry

(1985); Through the Straits of Armageddon (1987, co-edited with Paul Diehl), Decisions of the Highest

Order (1988, co-edited with Karl F. Inderfurth); America’s Secret Power (1989); Runoff Elections in

the United States (1993, co-authored with Charles S. Bullock, III); America As a World Power

(1995); Secret Agencies (1996); Bombs, Bugs, Drugs, and Thugs (2000); Fateful Decisions (2004, co-

edited with Karl F. Inderfurth); Strategic Intelligence (2004, co-edited with James J. Wirtz); Who’s

Watching the Spies? (2005, co-authored with Hans Born and Ian Leigh); American Foreign Policy

(2005, co-authored with Daniel Papp and John Endicott); and Seven Sins of American Foreign

Policy (2007). He has served as Special Assistant to the chair of the Senate Select Committee on

Intelligence (1975–76), Staff Director of the House Subcommittee on Intelligence Oversight

(1977–79), and Special Assistant to the chair of the Aspin-Brown Commission on Intelligence

(1995–1996). He is the Senior Editor of the international journal Intelligence and National Security.

Wolfgang Krieger is Professor of History at Philipps University in Marburg, Germany, and

a frequent contributor to the international journal Intelligence and National Security.

Ian Leigh is Professor of Law and the co-director of the Human Rights Centre at the

University of Durham. His books include In From the Cold: National Security and Parliamentary

Democracy (1994, with Laurence Lustgarten); Making Intelligence Accountable (2005, with Hans

Born); and Who’s Watching the Spies (2005, with Loch K. Johnson and Hans Born).

Minh A. Luong is Assistant Director of International Security Studies at Yale University

where he teaches in the Department of History. He also serves as an adjunct Assistant Professor

of Public Policy at the Taubman Center at Brown University.

Fred Manget is a member of the Senior Intelligence Service and a former Deputy General

Counsel of the CIA.

Stephen Marrin is an Assistant Professor of Intelligence Studies at Mercyhurst College. He

previously served as an analyst in the CIA and the Government Accountability Office.

Kathryn S. Olmsted is Professor of History at the University of California, Davis. She holds a

B.A. degree with Honors and Distinction in History from Stanford University, and a M.A. and

Ph.D. in History from the University of California, Davis. She is author of Challenging the Secret

Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI (University of North Carolina

Press, 1996) and Red Spy Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth Bentley (University of North Carolina

Press, 2002).

Mark Phythian is Professor of International Security and Director of the History and Govern-

ance Research Institute at the University of Wolverhampton, United Kingdom. He is the

author of Intelligence in an Insecure World (2006, with Peter Gill), The Politics of British Arms Sales

Since 1964 (2000), and Arming Iraq (1997), as well as numerous journal articles on intelligence

and security issues.

x

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

Paul R. Pillar is on the faculty of the Security Studies Program at Georgetown University.

Concluding a long career in the CIA, he served as National Intelligence Officer for the Near

East and South Asia from 2000 to 2005.

John Prados is an analyst of national security based in Washington, DC. He holds a Ph.D. from

Columbia University and focuses on presidential power, international relations, intelligence and

military affairs. He is a project director with the National Security Archive. Prados is author of

a dozen books, and editor of others, among them titles on World War II, the Vietnam War,

intelligence matters, and military affairs, including Hoodwinked: The Documents That Reveal How

Bush Sold Us a War, Inside the Pentagon Papers (edited with Margaret Pratt-Porter), Combined Fleet

Decoded: The Secret History of U.S. Intelligence and the Japanese Navy in World War II, Lost Crusader:

The Secret Wars of CIA Director William Colby, White House Tapes: Eavesdropping on the President

(edited), America Responds to Terrorism (edited), The Hidden History of the Vietnam War, Operation

Vulture, The Blood Road: The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnam War, Presidents’ Secret Wars: CIA

and Pentagon Covert Operations from World War II Through the Persian Gulf, Keepers of the Keys:

A History of the National Security Council from Truman to Bush, and The Soviet Estimate: U.S.

Intelligence and Soviet Strategic Forces, among others. His current book is Safe for Democracy: The

Secret Wars of the CIA.

Jeffrey T. Richelson is a Senior Fellow with the National Security Archive in Washington,

DC, and author of The Wizards of Langley, The US Intelligence Community, A Century of Spies, and

America’s Eyes in Space, as well as numerous articles on intelligence activities. He received his

Ph.D. in political science from the University of Rochester and has taught at the University of

Texas, Austin, and the American University, Washington, DC.

Richard L. Russell is Professor of National Security Studies at the National Defense Uni-

versity. He is also an adjunct Associate Professor in the Security Studies Program and Research

Associate in the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University. He previously

served as a CIA political-military analyst. Russell is the author of Weapons Proliferation and War

in the Greater Middle East: Strategic Contest (2005).

Robert David Steele (Vivas) is CEO of OSS.Net, Inc., an international open source intelli-

gence provider. As the son of an oilman, a Marine Corps infantry officer, and a clandestine

intelligence case officer for the Central Intelligence Agency, he has spent over twenty years

abroad, in Asia and Central and South America. As a civilian intelligence officer he spent three

back-to-back tours overseas, including one tour as one of the first officers assigned full time to

terrorism, and three headquarters tours in offensive counterintelligence, advanced information

technology, and satellite program management. He resigned from the CIA in 1988 to be the

senior civilian founder of the Marine Corps Intelligence Command. He resigned from the

Marines in 1993. He is the author of four works on intelligence, as well as the editor of a book

on peacekeeping intelligence. He has earned graduate degrees in International Relations

and Public Administration, is a graduate of the Naval War College, and has a certificate in

Intelligence Policy. He is also a graduate of the Marine Corps Command and Staff Course, and

of the CIA’s Mid-Career Course 101.

Mark Stout is a defense analyst at a think-tank in the Washington DC area. Previously, he

has served in a variety of positions in the Defense Department, the State Department, and the

CIA. He has a bachelor’s degree from Stanford University (1986) in Political Science and

xi

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

Mathematical and Computational Science, and a master’s degree in Public Policy from the John

F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University (1988). He is presently pursuing a

Ph.D. in military history with the University of Leeds.

Stan A. Taylor is an Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Brigham Young University in

Provo, Utah. He has taught in England, Wales, and New Zealand and in 2006 was a visiting

professor at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. He is founder of the David M.

Kennedy Center for International Studies at Brigham Young University. He writes frequently

on intelligence, national security, and US foreign policy.

Michael Warner serves as the Historian for the Office of the Director of National

Intelligence.

Nigel West is a military historian specializing in security and intelligence topics. He is the

European Editor of The World Intelligence Review and is on the faculty at the Center for

Counterintelligence and Security Studies in Washington, DC. He is the author of more than

two dozen works of non-fiction and most recently edited The Guy Liddell Diaries.

Thorsten Wetzling is a doctoral candidate at the Geneva Graduate Institute of International

Studies (IUHEI) and is writing his dissertation on international intelligence cooperation

and democratic accountability. He teaches seminars in political science and international

organization at the IUHEI.

James J. Wirtz is a Professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval

Postgraduate School, Monterey, California. He is the Section Chair of the Intelligence Studies

Section of the International Studies Association, and President of the International Security

and Arms Control Section of the American Political Science Association. Professor Wirtz is the

series editor for Initiatives in Strategic Studies: Issues and Policies, which is published by Palgrave

Macmillan.

xii

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

Glossary

AFIO Association of Former Intelligence Officers

AG Attorney general

Aman Agaf ha-Modi’in (Israeli military intelligence)

AVB Hungarian intelligence service

AVH Hungarian security service

BDA Battle damage assessment

BfV German equivalent of the FBI

BMD Ballistic missile defense

BND Bundesnachrichtendienst (German intelligence service)

BW Biological weapons

CA Covert action

CAS Covert Action Staff (CIA)

CBW Chemical/biological warfare

CCP Consolidated Cryptographic Program

CDA Congressionally directed action

CE Counterespionage

CHAOS Codename for CIA illegal domestic spying

CI Counterintelligence

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

CIC Counterintelligence Corps (US Army)

CIG Central Intelligence Group, precursor of CIA

CMS Community Management Staff

CNC Crime and Narcotics Center (CIA)

COINTELPRO FBI Counterintelligence Program

COMINT Communications Intelligence

CORONA Codename for first US spy satellite system

COS Chief of Station (CIA)

COSPO Community Open Source Program Office

CT Counterterrorism

CTC Counterterrorism Center (CIA)

xiii

CW Chemical weapons

D & D Denial and deception

DARP Defense Airborne Reconnaissance Program

DAS Deputy assistant secretary

DBA Dominant battlefield awareness

DC Deputies Committee (NSC)

DCD Domestic Contact Division (CIA)

DCI Director of Central Intelligence

D/CIA Director of Central Intelligence Agency

DDA Deputy Director of Administration (CIA)

DDCI Deputy Director for Intelligence (CIA)

DDO Deputy Director for Operations (CIA)

DDP Deputy Director for Plans (CIA, the earlier name for the DDO)

DDS & T Deputy Director for Science and Technology (CIA)

DEA Drug Enforcement Administration

DGI Cuban intelligence service

DGSE Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (French intelligence service)

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DI Directorate of Intelligence (CIA)

DIA Defense Intelligence Agency

DIA/Humint Defense Humint Service

DIE Romanian intelligence service

DINSUM Defense Intelligence Summary

DNI Director of National Intelligence

DO Directorate of Operations (the CIA’s organization for espionage and covert

action)

DoD Department of Defense

DOD Domestic Operations Division (CIA)

DOE Department of Energy

DOJ Department of Justice

DOS Department of State

DOT Department of Treasury

DP Directorate of Plans (from 1973, the CIA’s DO)

DS Bulgarian intelligence service

DST Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (France)

ELINT Electronic intelligence

EO Executive order

EOP Executive Office of the President

ETF Environmental Task Force (CIA)

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

FBIS Foreign Broadcast Information Service

FISA Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (1978)

FOIA Freedom of Information Act

FRD Foreign Resources Division (FRD)

FSB Federal’naya Sluzba Besnopasnoti (Federal Security Service, Russia)

GAO General Accountability Office (Congress)

GCHQ Government Communications Headquarters (the British NSA)

GEO Geosynchronous orbit

xiv

GLOSSARY

GEOINT Geospatial intelligence

GRU Soviet military intelligence

GSG German counterterrorism service

HEO High elliptical orbit

HPSCI House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence

HUMINT Human intelligence (assets)

HVA East German foreign intelligence service

I & W Indicators and Warning

IC Intelligence Community

IG Inspector general

IMINT Imagery intelligence (photographs)

INR Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Department of State

INTELINK An intelligence community computer information system

INTs Collection disciplines (IMINT, SIGINT, OSINT, HUMINT, MASINT)

IOB Intelligence Oversight Board (White House)

IRBM Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile

ISC Intelligence and Security Committee (UK)

ISI Inter-Services Intelligence (Pakistani intelligence agency)

IT Information technology

JCS Joint Chiefs of Staff

JIC Joint Intelligence Committee (UK)

Jstars Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar Systems

KGB Soviet secret police

KH Keyhole (satellite)

MASINT Measurement and signature intelligence

MFA Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MHBK Magyar Harcosok Bajtársi Közössége or Association of Hungarian Veterans

MI5 Security Service (UK)

MI6 Secret Intelligence Service (UK)

MONGOOSE Codename for CIA covert actions against Fidel Castro of Cuba (1961–62)

MOSSAD Israeli intelligence service

MRBM Medium Range Ballistic Missile

NBC Nuclear, biological, and chemical (weapons)

NCTC National Counterterrorism Center

NFIP National Foreign Intelligence Program

NGA National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

NGO Non-governmental organization

NIA National Intelligence Authority

NIC National Intelligence Council

NID National Intelligence Daily

NIE National Intelligence Estimate

NIO National Intelligence Officer

NKVD National Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the Soviet secret police under

Stalin

NOC Non-Official Cover

NPIC National Photographic Interpretation Center

NRO National Reconnaissance Office

NSA National Security Agency

xv

GLOSSARY

NSC National Security Council (White House)

NSCID National Security Council Intelligence Directive

NTM National Technical Means

OB Order of battle

OC Official Cover

ODNI Office of the Director of National Intelligence

OMB Office of Management and Budget

ONI Office of Naval Intelligence

OSD Office of the Secretary of Defense

OSINT Open-source intelligence

OSS Office of Strategic Services

P & E Processing and exploitation

PDB President’s Daily Brief

PFIAB President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (White House)

PM Paramilitary

RADINT Radar intelligence

RCMP Royal Canadian Mounted Police

SA Special Activities Division (DO/CIA)

SAS Special Air Service (UK)

SBS Special Boat Service (UK)

SDO Support to diplomatic operations

SHAMROCK Codename for illegal NSA interception of cables

SIG Senior Interagency Group

SIGINT Signals intelligence

SIS Secret Intelligence Service (UK, also known as MI6)

SISDE Italian intelligence service

SMO Support to military operations

SMS Secretary’s Morning Summary (Department of State)

SNIE Special National Intelligence Estimate

SO Special Operations (CIA)

SOCOM Special Operations Command (DoD)

SOE Special Operations Executive (UK)

SOG Special Operations Group (CIA)

SOVA Office of Soviet Analysis (CIA)

SSCI Senate Select Committee on Intelligence

StB Czech intelligence service

SVR Russian foreign intelligence service

TECHINT Technical intelligence

TELINT Telemetery intelligence

TIARA Tactical Intelligence and Related Activities

TISC Trade and Industry Select Committee (UK)

TPEDs Tasking, processing, exploitation, and dissemination

UAV Unmanned aerial vehicle (drone)

UB Polish Intelligence Service

UN United Nations

UNSCOM United Nations Special Commission

USFA US Forces in Austria

USIB United States Intelligence Board

xvi

GLOSSARY

USSOC United States Special Operations Command

USTR United States Trade Representative

VENONA Codename for NSA SIGINT intercepts against Soviet spying in America

VX A deadly nerve agent used in chemical weapons

WMD Weapons of mass destruction

xvii

GLOSSARY

Introduction

Loch K. Johnson

The meanings of intelligence

In a “handbook” for intelligence studies, the place to begin is with a definition of what

intelligence means. Formally, professional officers define the term in both a strategic and a

tactical sense. Broadly, a standard definition of strategic intelligence is the “knowledge and

foreknowledge of the world around us – the prelude to Presidential decision and action.”

1

At

the more narrow or tactical level, intelligence refers to events and conditions on specific

battlefields or theaters of war, what military commanders refer to as “situational awareness.” In

this volume, the focus is chiefly on strategic intelligence, that is, the attempts by leaders to

understand potential risks and gains on a national or international level.

The phrase may refer to concerns about threats at home – subversion by domestic radicals

or the infiltration of hostile intelligence agents or terrorists inside a nation’s borders; or

it may focus on dangers and opportunities overseas. In the first instance in the United

States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the lead agency; in the second instance, the

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and a host of military intelligence organizations take

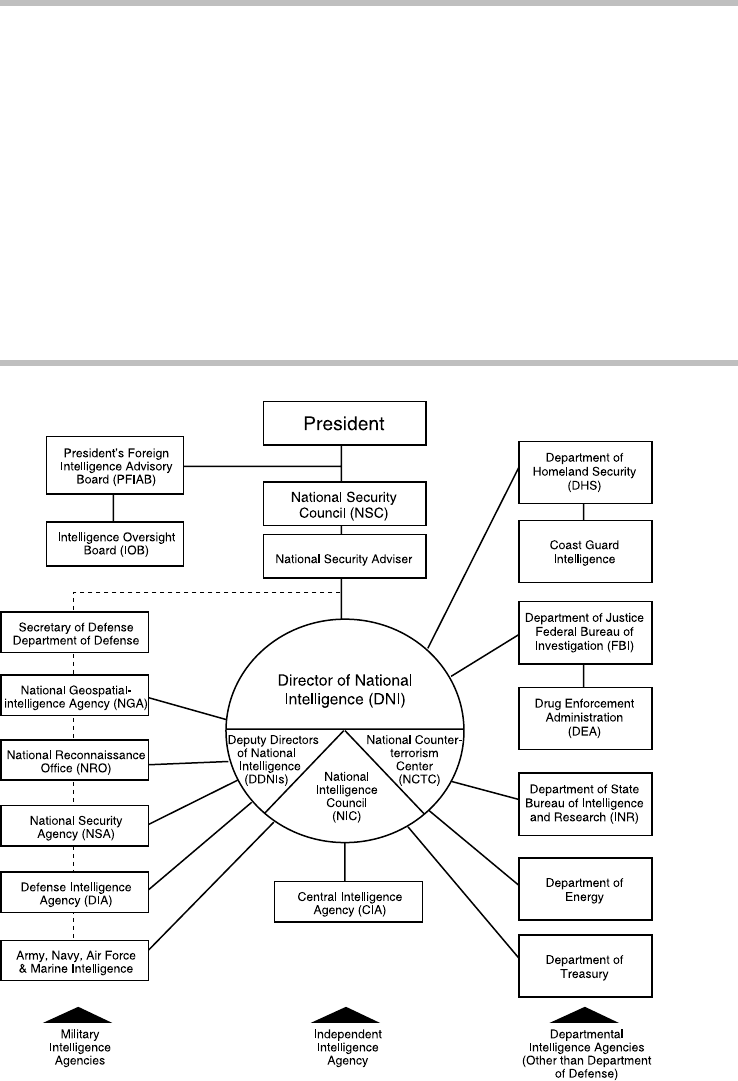

the lead. (See Appendix A for an organizational diagram depicting America’s sixteen major

intelligence agencies, and Appendix B for the names of the leaders of the “intelligence

community”).

In addition to the two geographic dimensions (global versus local), “strategic intelligence”

has a number of other possible meanings. Most frequently, the phrase refers to information, a

tangible product collected and analyzed (assessed or interpreted) in hopes of achieving a deeper

comprehension of subversive activities at home or political, economic, social, and military

situations around the world. An example of an intelligence question at the international, stra-

tegic level would be: to what extent are Al Qaeda cells located in and operating from the nation

of Pakistan? A related question: do these cells enjoy allies in that nation’s official intelligence

and military bureaucracy? In contrast, at the tactical level overseas, one can imagine a US

military commander in Iraq demanding to know the location of the most well-armed strong-

holds of the insurgency in the suburbs of Baghdad. Or how much additional armor is necessary

on the side paneling of Humvees to defend against rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) fired by

insurgents in Iraq?

1

On the home front, a strategic intelligence question for American intelligence officers might

be: how many Chinese espionage agents are inside the United States and what are their

objectives? Or: are there any more home-grown terrorists like Timothy McVeigh, the man

convicted of bombing a federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995, and are they planning the

use of violence against other government institutions inside the nation?

Intelligence as information is different from the kind of everyday information one can find

in the local library, because intelligence usually has a secret component. Those in the business of

gathering intelligence blend together the open-source information gleaned from the public

domain (newspapers, magazine, blogs, public speeches) with information that other nations try

to keep hidden. The hidden information must be ferreted out of encoded communications or

stolen from safes and vaults, locked offices, guarded military and intelligence installations, and

other denied areas – a potentially dangerous task involving the penetration of an enemy’s camp

and its concentric circles of defense, from barbed-wire barriers patrolled by armed security

forces and sentry dogs to sophisticated electronic alarms, surveillance cameras, and motion

detectors. As intelligence scholar Abram N. Shulsky has written, intelligence often entails access

to “information some other party is trying to deny.”

2

While the overwhelming percentage – sometimes upwards of 95 percent

3

– of the informa-

tion mix provided to America’s decision-makers in the form of intelligence reports is based on

open sources, the small portion derived from clandestine operations can be vital, providing just

the right secret “nugget” necessary to understand the likely plans of a foreign adversary. After

all, the New York Times provides good information about world affairs for the most part, but it

has no reporters inside North Korea, Al Qaeda cells, or several places around the globe that

might be of interest to the United States (say, Angola or Darfur in Sudan). So the government

must send its own intelligence officers to such places. Even in locations from which the Times

reports on a regular basis, such as France and Germany, its correspondents may not be asking

the questions that an American secretary of state, treasury, or defense may wish to have

answered. That is why the United States has a CIA and other secret services: to go where

journalists may not be allowed to go, or where they are not assigned to go by their managing

editors, and to seek the answers to questions that a nation’s leaders may need to know beyond

what may interest the average newspaper reader.

In short, the world has secrets that the United States and other nations may want to know

about, especially if they threaten the safety and prosperity of their citizens or their foreign allies.

Sometimes stealing this kind of information is the only way to acquire it. Beyond secrets that

may be obtained through theft or surveillance by satellite cameras and listening devices (such

as the number, location and capabilities of Chinese nuclear submarines and intercontinental

missiles), the world also has mysteries, that is, information that may well be impossible to know

about regardless of how many newspaper reporters and spies one may have. Who knows, for

instance, how long Kim Jong il will survive as the leader of North Korea, or what kind of

regime will follow in his wake? Who knows who will succeed President Vladimir Putin in

Russia? The best one can hope for, from an intelligence point of view, is an educated guess by

experts who have carefully studied such questions. These hunches are called “estimates” by

intelligence professionals in the United States, or “assessments” by their British counterparts.

A useful metaphor for thinking about strategic intelligence is the jigsaw puzzle. The

aspiration in both cases is to gather as many pieces as possible to provide a thorough picture. In

the case of intelligence, the “picture” one seeks is full information about subversive activities

at home or the capabilities and intentions of existing and potential adversaries on the world

stage. Most of the intelligence pieces of the puzzle will be from publicly available documents;

some will be derived from spying, whether with human agents or machines (such as satellites

2

LOCH K. JOHNSON

and U-2 reconnaissance aircraft). Almost always there will be missing pieces: the mysteries of

the world or, in some instances, secrets that are so well hidden or guarded that they remain out

of sight or out of reach. The great frustration of strategic intelligence is that rarely does one

operate in an environment of full transparency. Rather, the world is replete with uncertainties

and, as a result, intelligence gaps are inevitable and sometimes result in the failure of intelligence

officials to provide robust and timely warning of dangers. In the words of Secretary of State

Dean Rusk, “Providence has not given mankind the capacity to pierce the fog of the future.”

4

No one has a crystal ball.

At times, intelligence failures are the result of missing pieces of the puzzle. Sometime, though,

mistakes stem from the inability of individuals to accurately analyze the meaning of the pieces

that are available, improperly judging their meaning and significance. Usually failures are a

product of both problems: an incomplete jigsaw puzzle and an inability to decipher the com-

plete picture from the few pieces one does have. Thus, both an exhaustive collection of

information and a sagacious analysis of its meaning are indispensable for skillfully estimating or

predicting what events may mean for a nation’s future. Above all, every nation seeks informa-

tion that will provide an adequate alert about impending attacks – “indicators and warnings”

or I & W, in the vernacular of professional intelligence officers. The surprise attacks against the

United States at Pearl Harbor in 1941 and, more recently, against the Twin Towers and

the Pentagon in 2001 illustrate the importance of accurately, timely, and specific I & W

intelligence.

A nation seeks to know much more, though, than warnings about potential attacks. For

example, leaders want to understand the weapons capabilities of potential adversaries, such as

Iraq in 2002. In that instance, US and British intelligence agencies estimated that the Saddam

Hussein regime probably had weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). America and the United

Kingdom went to war against Iraq, in part, to eliminate these weapons – only to discover that

the intelligence estimates had been incorrect. There were no WMDs to be found in Iraq in

2003, when the British and the United States invaded. The 9/11 and WMD cases vividly

underscore the importance of having reliable intelligence, what President George H.W. Bush

often referred to as the nation’s “first line of defense.”

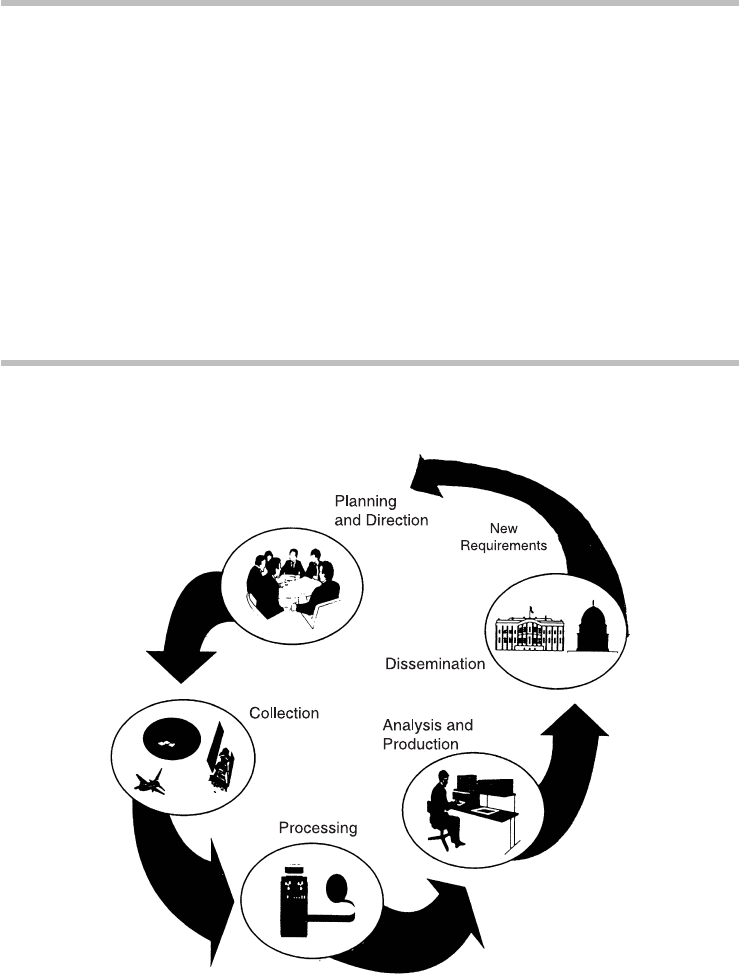

Intelligence has a second meaning beyond that of an information product, such as the

number of tanks in Iran and their firepower. Intelligence is also thought of as a process: a series of

interactive steps, formally referred to as an “intelligence cycle.” (See Appendix C for a diagram

of the cycle.) The process begins with intelligence managers and policy officials planning what

information to gather related to threats and opportunities at home and abroad. They must also

determine what methods to use in the gathering of this information – the right mix of human

agents and surveillance machines, for instance. Then the information is collected, to the extent

one can succeed in this regard against adversaries who are skillful at concealing their activities.

This information must be processed into readable text, say, from an intercepted telephone

conversation in Farsi; and the contents must be analyzed for its meaning to American interests –

all as quickly as possible. Finally, the “finished” information – that is, intelligence that has been

studied and interpreted – must be disseminated to those officials in high public office or troops

in the field who rely on these insights as they plan their next policy initiatives or military

moves.

From a third perspective, intelligence may also be thought of as a set of missions carried out by

secret agencies. The premier mission is that of collecting and analyzing information. Important,

too, though, is the mission of counterintelligence and, its subsidiary concern, counterterrorism.

These terms refer to the methods by which nations try to thwart secret operations directed

against them by hostile foreign intelligence services or terrorist organizations. Yet another

3

INTRODUCTION

mission is covert action – the secret intervention in the affairs of other nations or organizations

in hopes of improving America’s security and other interests, such as economic prosperity.

Covert action goes by a number of euphemisms, including “the quiet option” (that is, less

noisy than sending in the Marines), the “third option” (between diplomacy and open war), or

“special activities.”

Before turning to an examination of these missions, a fourth and final definition of intelli-

gence is offered: intelligence may be considered a cluster of people and organizations established to

carry out the three missions – the sixteen entities and staff of Appendix A. “Make sure you

check with intelligence before completing your invasion plans,” the prime minister might

advise his minister of defense. “Get intelligence on the line and find out the exact coordinates

of the insurgents in Kirkuk,” a US artillery commander in Iraq might order.

The US intelligence “community,” as the cluster is called, is led by the president and the

National Security Council (NSC), who in turn rely on a Director of National Intelligence

(DNI, before 2005 known as the Director of Central Intelligence or DCI) to manage the

sixteen agencies. (Appendix B provides a list of the twenty men – no women yet – who have

served as either DCI or DNI.) According to various newspaper accounts, the intelligence

community or IC employs over 150,000 people and has a budget of some $44 billion a year,

making it the largest and most costly collection of intelligence organizations ever assembled by

any nation in history.

The CIA and the FBI are the most well-known of these agencies. The CIA is located in a

campus-like setting along the Potomac River in the Washington, DC, suburb of Langley,

Virginia, fourteen miles north of the White House. The CIA is mainly responsible for

managing the collection of intelligence abroad by human agents, and for analyzing the informa-

tion gathered by agents and machines. The FBI has a primarily domestic focus, with responsi-

bilities for tracking the activities of suspected subversives, terrorists, and foreign intelligence

officers inside the United States. Several of the remaining intelligence agencies are embedded

within the organizational framework of the Defense Department, including the National

Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), which handles the photographic side of foreign sur-

veillance; the National Security Agency (NSA), responsible for codebreaking and electronic

eavesdropping; the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), chartered to coordinate the

development, launching, and management of surveillance satellites; the Defense Intelligence

Agency (DIA), in charge of military intelligence analysis; Coast Guard Intelligence, a part

of the new Department of Homeland Security; and the four military intelligence services,

Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines, each gathering tactical intelligence related to their

missions.

Joining the CIA and the FBI on the civilian side of intelligence (in the sense that they are

located in civilian departments, rather than within the Department of Defense) are the Bureau

of Intelligence and Research (INR) in the Department of State; an intelligence unit in the

Department of the Treasury; the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in the Department

of Justice; an intelligence unit in the Department of Homeland Security; and an intelligence

unit in the Department of Energy, responsible for tracking the world’s supply of uranium and

other nuclear materials, as well as guarding the nation’s weapons laboratories.

Among all of these organizations, the CIA is unique in that it stands outside any Cabinet

department; it is an independent agency. It is unique as well in being the centerpiece of the

National Security Act of 1947, the founding legislation for America’s modern intelligence

establishment. Originally, President Harry S. Truman envisioned the CIA as the central

coordinating structure for American intelligence, designed to draw together the work of all the

other agencies into a package that a president could deal with more readily than hearing

4

LOCH K. JOHNSON

separately from an array of agencies. The DCI was the individual Truman chose to manage this

important coordinating role.

The plan never worked, though, because Truman – buckling under pressure from the

Pentagon, which opposed a strong civilian leader for intelligence – failed to provide the DCI

with adequate budget and appointment power over all of the agencies. Instead, the DCI became

the leader of the CIA, but only the titular head of the full intelligence community.

After the 9/11 attacks, reformers vowed to correct this flaw, but again the Pentagon was able

to dilute efforts to establish a strong DNI with funding and appointment powers over all

of America’s intelligence agencies. The DNI, like the DCI before, became the nation’s chief

spymaster largely in name only, with each of the sixteen agencies having a large degree of

autonomy, enclosed or “stovepiped” within their own walls and enjoying considerable leeway

to resist the orders of a DNI. This resistance was especially notable from the defense intelligence

agencies – NGA, NSA, NRO, DIA, and the military services – who enjoyed the bureaucratic

protection of the powerful secretary of defense, a member of the NSC.

The Office of the DCI had been located on the CIA’s seventh floor. Since 2005, soon after a

law was passed that replaced the DCI with a DNI, the nation’s intelligence chief has moved

from the CIA into temporary quarters at the DIA, also along the Potomac, only this time south

of the White House by seven miles. A search is underway for a building inside the District of

Columbia where the DNI can set up shop closer to the White House.

The DNI move out of the CIA Headquarters Building cast into doubt that agency’s role as

the central coordinating entity in the government for intelligence, as did its mistakes related to

9/11 and the Iraqi WMD fiasco. Consequently, in the quest for a more effective intelligence

community after the 9/11 attacks, the United States ended up – ironically – with a weakened

CIA and an even more emasculated intelligence chief, now removed from the one major

resource that had given the nation’s spy chief some clout in Washington circles: the analytic

resources of the CIA.

The methods of intelligence

Regardless of which aspect of intelligence one has in mind – product, process, mission, or

organization – the bottom line is that good governmental decisions rely on accurate, complete,

unbiased, and timely information about the capabilities and intentions of other nations, terrorist

organizations, and subversive groups. “Every morning I start my day with an intelligence

report,” President Bill Clinton once remarked. “The intelligence I receive informs just about

every foreign policy decision we make.”

5

The intelligence agencies face quite a challenge in meeting the government’s needs for

insightful information about threats and opportunities. The world has some 191 countries and

an untold number of organizations and groups, many that are hostile toward the United States

and its allies. Further, these adversaries have become skillful in hiding their plans and operations

from the prying eyes of espionage agents and spy machines. North Korea, for example, has

constructed deep underground bunkers, where its scientists work on nuclear weaponry out

of the sight of foreign surveillance satellites. A former US secretary of state has commented on

the fear of intelligence failure: “The ghost that haunts the policy officer or haunts the man who

makes the final decision is the question as to whether, in fact, he has in his mind all of the

important elements that ought to bear upon his decision, or whether there is a missing piece

that he is not aware of that could have a decisive effect if it became known.”

6

In their search for as perfect information about risks and opportunities as they can find,

5

INTRODUCTION

nations turn to a wide array of spying methods. Foremost among them, for nations with large

enough budgets, are the expensive instruments of technical intelligence (or “techint”). By

definition, techint refers chiefly to imagery intelligence (“imint”) and signals intelligence

(“sigint”). Imint employs photography, such as snapshots of enemy installations by surveillance

satellites, for example; sigint encompasses the interception and analysis of communications

intelligence, whether telephone conversations or e-mail transmissions.

In a time of accelerated technological advances around the world, the United States faces

serious challenges in trying to maintain an information advantage over other nations. Its

current edge in satellite photography is rapidly eroding. In 1999, the private US company Space

Imaging launched a surveillance satellite named Ikonos II that yields photographs almost as

detailed as the American government’s most secret satellite photography, pictures of almost

any part of the planet for sale to anyone with cash or a credit card. Within a few years, Iran and

other nations at odds with the United States will be able to manufacture home-grown spy

satellites or acquire commercially available substitutes (the Rent-a-Satellite option) which will

provide them with their own capacity for battlefield transparency – a huge advantage for the

United States during its wars against Iraq in 1991 and 2003.

America’s advantages in signals intelligence are in decline as well. The listening satellites of

the NSA are designed to capture analog communications from out of the air. The world,

though, is rapidly switching to digital cell phones, along with underground and undersea

fiber-optic modes of transmission – glass conduits (“pipe lights”) that rely on light waves

instead of electrons to carry information. These new forms of communication are much harder

to tap, leaving the NSA with a sky full of increasingly irrelevant satellites. Furthermore, the

NSA has traditionally depended on its skills at decoding to gain access to foreign diplomatic

communications; but nations and terrorist groups are growing more clever at encrypting

their messages with complex, computer-based technologies that can stymie even the most

experienced NSA cryptologists. Under pressure from the US software industry and the

Department of Commerce, the Clinton administration decided in 1999 to allow the export of

advanced American software that encrypts electronic communications, making it more difficult

for the NSA and the FBI to decipher the communications of foreign powers that might intend

harm to the United States. Responding to market pressures of its own, the European Union

is considering the removal of its restrictions on the sale of encryption software by European

companies.

America’s intelligence community suffers as well from an excessive redundancy built into its

collection systems, with satellites, airplanes, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) often staring

down at the same targets. Moreover, many of the satellites are gold-plated Cadillac de Ville

models, with all the latest accessories. For certain missions, as in the broad coverage of a

battlefield, they are valuable; but for many others, they could be replaced with less expensive,

smaller satellites: serviceable Chevies. (The smaller the satellite, the less expense involved in

positioning it in space, since launch costs are linear with weight.) The U-2 Dragon Lady piloted

aircraft and the RQ-4A Global Hawk UAV are also far less expensive than the large, fancy

satellites and much more effective in locating foes in places like Iraq and Afghanistan.

One of the most important responsibilities of the intelligence agencies is to warn the United

States about terrorist efforts to acquire weapons of mass destruction, an extraordinarily difficult

mission. The case of a suspected chemical weapons plant in Sudan is illustrative. In 1998 at a

pharmaceutical factory near Khartoum, CIA sensing devices sniffed out what seemed to be the

chemical Empta, a precursor for the production of the deadly nerve agent VX. The intelligence

community had already collected signals intelligence and agent reports that linked the factory

in the past with the terrorist Bin Laden and his Al Qaeda organization. Putting two and two

6

LOCH K. JOHNSON

together, analysts estimated with a high degree of confidence that the factory was manu-

facturing chemical weapons. This intelligence led the Clinton administration to attack the

facility with cruise missiles. In response, the Sudanese government denounced the United

States and claimed that it had gone to war against an aspirin factory. The CIA stuck with its

original assessment, but did acknowledge that detective work of this kind is difficult and

imprecise. “The turning of a few valves can mean the difference between a pharmaceutical

company and a chemical or biological plant,” said the agency’s leading proliferation specialist.

7

The failure of the CIA to anticipate the Indian nuclear test in 1998 is also instructive.

America’s intelligence agencies were well aware that the Indians intended to accelerate their

nuclear program. After all, this is what top-level party officials had been saying publicly

throughout the Indian election season. Even the average tourist wandering around India in the

spring of that year, listening to the local media, would have concluded that a resumption of

the program was likely. What surprised the intelligence agencies was how fast the test had

taken place. It was “a good kick in the ass for us,” admits a senior CIA official.

8

In part the

miscalculation was a result of what a CIA inquiry into the matter, led by retired Admiral David

Jeremiah, referred to as “mirror imaging.” Agency analysts assumed that Indian politicians were

just like their American counterparts: both made a good many campaign promises, few of

which were ever kept. To win votes for boldness, Indian politicians in the victorious party (the

BJP) had promised a nuclear test; now that the election hoopla was over, surely they would back

away from this rash position. Such was the thinking at the CIA.

Further clouding accurate analysis by CIA analysts were successful efforts by officials in India

to evade America’s spy satellites. The Indians knew exactly when the satellite cameras would

be passing over the nuclear testing facility near Pokharan in the Rajasthan Desert and, in

synchrony with these flights (every three days), scientists camouflaged their preparations.

Ironically, US officials had explicitly informed the Indian government about the timing of

US satellite coverage for South Asia, in hopes of impressing upon them the futility of trying to

conceal test activity. Even without this unintended assistance, though, the Indians could have

figured out the cycles for themselves, for even amateur astronomers can track the orbits of spy

satellites.

Moreover, the Indians had become adroit at deception, both technical and political. On the

technical side, the ground cables normally moved into place for a nuclear test were nowhere to

be seen in US satellite photographs of the site. The Indians had devised less visible ignition

techniques. The Indians also stepped up activities at their far-removed missile testing site in an

attempt to draw the attention of spy cameras away from the nuclear testing site. On the political

side, Indian officials expanded their coordinated deception operation by misleading American

and other international diplomats about the impending nuclear test, offering assurances that it

was simply not going to happen.

Finally, a dearth of reliable intelligence agents (“assets”) contributed to the CIA’s blindness.

During the Cold War, spending on techint far outdistanced spending on old-fashioned

espionage, known as human intelligence or “humint.” A strong tendency exists among those

who make budget decisions for national security to focus on warheads, throw weights, missile

velocities, and the specifications of fancy spy satellites – things that can be measured. Humint, in

contrast, relies on the subtle recruitment of foreign agents, whose names and locations must be

kept highly secret and are not the subject of budget hearings. Yet, Ephraim Kam has emphasized

the importance of humint. An adversary’s most important secrets, he notes, “often exist in the

mind of one man alone.. . or else they are shared by only a few top officials.”

9

This kind of

information may be accessible only to an intelligence officer who has recruited someone inside

the enemy camp.

7

INTRODUCTION

During the Cold War, South Asia received limited attention from the US intelligence

agencies, compared to their concentration on the Soviet Union and its surrogates; therefore,

building up an espionage ring in this region after the fall of communism still had a long ways to

go at the time of the Indian nuclear tests. These excuses notwithstanding, American citizens

may have wondered with a reasonable sense of indignation – not to say outrage – why their

well-funded intelligence community proved ignorant of what was going on inside the largest

democracy and one of the most open countries in the world.

Far more difficult than keeping an eye on India is the challenge of gaining access to intelli-

gence on reclusive terrorist organizations and renegade states like Iran and North Korea –

dangerous, isolated, and unpredictable adversaries known to leave footprints of fire. It is difficult

as well to keep track of companies engaged in commercial transactions that aid and abet the

spread of weaponry, like the German corporations that secretly assisted the Iraqi weapons

buildup and the construction of the large chemical weapons plant at Rabta in Libya.

During the Carter administration, the nation was reminded of the importance of humint

when Iranian student militants took American diplomats hostage inside the US embassy in

Tehran. America’s satellites had good photographs of Tehran and the embassy compound; but

to plan a rescue operations, the White House and the CIA needed information about the

whereabouts of the hostages inside the embassy. Recalls one of the planners:

We had a zillion shots of the roof of the embassy and they were magnified a hundred times. We

could tell you about the tiles; we could tell you about the grass and how many cars were parked

there. Anything you wanted to know about the external aspects of the embassy we could tell you in

infinite detail. We couldn’t tell you shit about what was going on inside that building.

10

The methods of intelligence collection became skewed as well during the Cold War. Awed

by the technological capabilities of satellites and reconnaissance airplanes (U-2s, SR-21s,

UAVs), officials channeled most of the intelligence budget into surveillance machines capable

of photographing Soviet tanks and missiles silos and eavesdropping on telephone conversations

in communist capitals. Human spy networks became the neglected stepchild of intelligence.

Machines certainly have their place in America’s spy defenses and they played an important

role in Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks, as US satellite cameras stared down at Kabul and

Kandahar, and UAVs swooped into mountain valleys in search of Al Qaeda terrorists and their

Taliban accomplices. But these cameras cannot peer inside caves or see through tents where

terrorists gather. A secret agent in the enemy’s camp – humint – is necessary to provide advance

warning of future terrorist attacks. Humint networks take time to develop, though, and only

recently have the last DCI (Porter Goss) and the new DNI (John Negroponte) launched major

recruitments drive to hire into the intelligence community Americans with language skills and

an understanding of Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, and other parts of the world largely ignored by

the United States until now. American intelligence officers with these skills are needed to

recruit local agents overseas who carry out the actual espionage for the CIA. The 9/11 attacks

and the Iraqi WMD controversy accelerated these recruitment efforts, but it has proven difficult

to find Arabic, Farsi, and Pushto speakers who are citizens of the United States and who want to

work for the CIA abroad at a modest government salary and in conditions that are less than

luxurious – and sometimes downright dangerous.

8

LOCH K. JOHNSON

The intelligence missions

Collection-and-analysis. The foremost intelligence mission is to gather intelligence, whether by

technint or humint, then analyze its meaning, bringing human insight to bear on the mountain

of data that has been collected. At the beginning of every administration, senior officials work

with the DNI to prepare a “threat assessment” – a priority listing of the most dangerous

circumstances facing the United States. These officials then decide how much money from the

annual intelligence budget will be spent on the collection of information against each target

nation or group.

Throughout the Cold War, the United States concentrated mainly on gathering intelligence

against the Soviet Union and other communist powers, giving far less attention to the rest

of the world. Terrorism has been on the list of intelligence priorities for decades, but until

September 11, 2001, it was treated by the intelligence agencies as only one of several assign-

ments. Now it has jumped to a position of preeminence on America’s threat list, resulting in a

greater focus of US intelligence resources on Osama bin Laden and his associates.

When a recent director of the NSA was asked what his major problems were, he replied, “I

have three: processing, processing, and processing.”

11

In this phase of the intelligence cycle,

information is converted from “raw” intelligence – whether in Arabic or a secret code – into

plain English (see Appendix C). Beyond needing more language translators, the chief difficulty

faced by intelligence officers is the sheer volume of information that pours into their agencies.

Each day millions of telephone intercepts and hundreds of photographs from satellites stream

back to the United States. A former intelligence manager recalls feeling as though he had a fire

hose held to his mouth.

The task of sorting through this flood of information to isolate the important facts from the

routine can hinder quick access to key information. Before the September attacks, for example,

FBI agents dismissed as routine a CIA report concerning two individuals headed for the

United States and suspected of associating with terrorists. The men turned out to be among the

nineteen suicide hijackers of 9/11.

Once information is processed, it must be studied by experts for insights into the intentions

of our adversaries – the step known as analysis. If the CIA is unable to provide meaning to the

information gathered by the intelligence community, all the earlier collecting and processing

efforts are for nought. Good analysis depends on assembling the best brains possible to evaluate

global events, drawing upon a blend of public knowledge and stolen secrets. Once again a

major liability is the CIA’s shortage of well-educated Americans who have deep knowledge of

places like Afghanistan and Sudan. While all of the intelligence agencies have been scrambling

to redirect their resources from the communist world to the forgotten world of the Middle

East and Southwest Asia, hiring and training outstanding analysts takes time, just like the

establishment of new humint spy rings.

Finally, the analyzed intelligence is disseminated to policymakers. It must be relevant, timely,

accurate, comprehensive, and unbiased. Relevance is essential. Intelligence reports on drug-

trafficking in Colombia are good to have, but what the White House and Whitehall want right

now is knowledge about Bin Laden’s operations. Analysts can become so wedded to their own

research interests (say, the efficiencies of Russian rocket fuel) that they fail to produce what

policymakers really want and need to know.

Timeliness is equally vital. The worst acronym an analyst can see scrawled across an intelli-

gence report is OBE – “overtaken by events.” Assessments on the whereabouts of terrorists are

especially perishable, as the United States discovered in 1999 when the Clinton administration

fired cruise missiles at Bin Laden’s supposed encampment in the Zhawar Kili region of

9

INTRODUCTION

Afghanistan’s Paktia Province, only to learn that he had departed hours earlier. Similarly, the

accuracy of information is critical. One of America’s worst intelligence embarrassments came

in 1999 when the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) misidentified the Chinese

embassy in Belgrade as a weapons depot, leading to a NATO bombing of the building and the

death of Chinese diplomats.

Intelligence must be comprehensive as well, drawn from all sixteen intelligence agencies and

coordinated into a meaningful whole – what intelligence officers refer to as “all-source fusion”

or “jointness.” Here one runs into the vexing problem of fragmentation within the so-called

intelligence “community” – a misnomer if there ever was one. The US secret agencies often act

more like separate medieval fiefdoms than a cluster of agencies working together to provide the

president with the best possible information from around the world.

Intelligence must also be free of political spin. An analyst is expected to assess the facts in a

dispassionate manner. Usually intelligence officers maintain this ethos, but occasionally they

have succumbed to the wiles of White House pressure for “intelligence to please” – data that

supports the president’s political agenda rather than reflecting the often unpleasant reality that

an administration’s policy has failed.

Much can go wrong, and has gone wrong, with intelligence collection-and-analysis. For it to

function properly in America’s three ongoing wars – against insurgents in Iraq, remanent

Taliban fighters in Afghanistan, and the global struggle against terrorism – collection must

employ an effective combination of machines and human spies. Moreover, data processing must

be made more swift and more discerning in the discrimination of wheat from chaff. Analysts

must have a deeper understanding of the foreign countries that harbor terrorist cells, as well as a

better comprehension of what makes the terrorists tick. Further, at the end of this intelligence

pipeline, the information provided to the policymaker must be pertinent, on time, reliable,

comprehensive, and unbiased. Finally, the policymakers must have the courage to hear the truth

rather than brush it aside, as President Lyndon B. Johnson sometimes did with intelligence

reports on Vietnam that concluded America’s involvement in the war was leading to failure.

12

Counterintelligence. The term counterintelligence (CI) encompasses a range of methods used

to protect the United States against aggressive operations perpetrated by foreign intelligence

agencies and terrorist groups. These operations include attempts to infiltrate the CIA, FBI, and

other US intelligence agencies through the use of double agents, penetration agents (moles),

and false defectors. Counterintelligence employs two approaches: security and counter-

espionage. Security is the defensive side of CI: physically guarding US personnel, installations, and

operations against hostile forces. Among the defenses employed by America’s secret agencies

are codes, alarms, watchdogs, fences, document classifications, polygraphs, and restricted

areas. Counterespionage represents the more aggressive side of CI, with the goal, above all, of

penetrating with a US agent the inner councils of a foreign intelligence service or terrorist cell.

Aldrich Ames (CIA) and Robert Hannsen (FBI), the premier spies in the United States run

by the Soviet Union and then Russia, caused the most grievous harm to America’s intelligence

operations and stand as the greatest counterintelligence failures in US history. As a result of

their handiwork in stealing top-secret (“blue-border”) documents – for which the KGB, and

later, the Russian SVR paid Ames alone over $4 million – the espionage efforts of the CIA and

the FBI against the Soviet Union lay in tatters at the end of the Cold War. The Kremlin

executed at least nine of the CIA’s assets in Russia and rolled up hundreds of operations. Ames

and Hannsen also disclosed some of America’s most sensitive technical intelligence capabilities

to their Moscow handlers, including (from Hannsen) details about US listening devices in the

new Russian embassy in Washington, DC.

Covert action. Here is the most controversial mission of the three, as exemplified by the Bay of

10

LOCH K. JOHNSON

Pigs fiasco in 1961 – a failed paramilitary covert action against the Castro regime in Cuba.

Covert action consists of aiming secret propaganda at foreign nations, as well as using political,

economic, and paramilitary operations in an effort to influence, disrupt, or even overthrow their

governments (as in Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, and – without success – Iraq in the 1990s).

The objective of covert action is to secretly shape events overseas, in so far as history can be

shaped by mere mortals, in support of US foreign policy goals.

The most extensively used form of covert action has been propaganda. As a supplement to

the overt information released to the world by the United States under the rubric of “public

diplomacy,” the CIA over the years has pumped through its wide network of secret media

agents a torrent of covert propaganda that resonates with the overt themes. These foreign agents

have included reporters, magazine and newspaper editors, television producers, talk show hosts,

and anyone else in a position to disseminate without attribution the perspectives of the US

government as if they were their own. One of the major examples of a CIA propaganda

operation was the financing of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty during the Cold War.

These radio stations broadcast into the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe with programming

geared to break the communist government’s totalitarian control over news, entertainment, and

culture, as well as to advance America’s views of the world. These programs are credited with

having helped sustain dissident movements behind the Iron Curtain, and to have contributed to

the eventual fall of Soviet communism and Moscow’s control over Eastern Europe.

Of greater controversy were the CIA’s propaganda efforts in Chile during the 1960s

and 1970s. In 1964, the CIA spent $3 million – a staggering sum at the time – to blacken the

name of Salvador Allende, the socialist presidential candidate with suspected ties to the Soviet

Union. Allende was elected, nonetheless, in a free and open democratic electoral process. The

CIA continued its propaganda operations, now designed to undermine the Allende regime,

spending an additional $3 million between 1970 and 1973. According to US Senate investiga-

tors, the forms of propaganda included press releases, radio commentary, films, pamphlets,

posters, leaflets, direct mailings, paper streamers, and wall paintings. The CIA relied heavily on

images of communist tanks and firing squads, and paid for the distribution of hundreds of

thousands of copies, in this very Catholic country, of an anti-communist pastoral letter written

many years earlier by Pope Pius XI.

Covert action sometimes takes the form of financial aid to pro-Western politicians and

bureaucrats in other nations, money used to assist groups in their electoral campaigns or for

party recruitment. Anti-communist labor unions in Europe received extensive CIA funding

throughout the Cold War, as did many anti-communist political parties around the world. One

well-known case involved the Christian Democratic Party in Italy during the 1960s, when it

struggled against the Italian Communist Party in elections. The CIA has also resorted to the

disruption of foreign economies. In one instance, during the Kennedy administration (although

without the knowledge of the president), the CIA hoped to spoil Cuban–Soviet relations by

lacing sugar bound from Havana to Moscow with an unpalatable, though harmless, chemical

substance. A White House aide discovered the scheme and had the 14,125 bags of sugar

confiscated before they were shipped to the Soviet Union. Other methods have reportedly

included the incitement of labor unrest, the counterfeiting of foreign currencies, attempts to

depress the world price of agriculture products grown by adversaries, the contamination of oil

supplies, and even dynamiting electrical power lines and oil-storage facilities, as well as mining

harbors to discourage the adversary’s commercial shipping ventures.

13

The paramilitary, or war-like, forms of covert action have stirred the most controversy.

This category includes small- and large-scale “covert” wars, which do not remain covert for

long; training activities for foreign military and police officers; the supply of military advisers,

11

INTRODUCTION

weapons, and battlefield transportation; and the planning and implementation of assassination

plots. This last endeavor has been the subject of considerable criticism and debate, and was

finally prohibited by executive order in 1976 – although with a waiver in time of war. That year

congressional investigators uncovered CIA files on assassination plots against several foreign

leaders, referred to euphemistically in secret CIA documents as “termination with extreme

prejudice” or simply “neutralization.” At one time the CIA established a special group, called

the “Health Alteration Committee,” to screen assassination proposals. The CIA’s numerous

attempts to murder Fidel Castro all failed; and its plot against Congolese leader Patrice

Lumumba, requiring a lethal injection of poison into his food or tooth paste, became a moot

point on the eve of its implementation when Lumumba was murdered by a rival faction

in Congo.

After the end of the Cold War, spending for covert action went into sharp decline. It has

been revived, though, with the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and against global terrorists. The most

lethal new form of paramilitary covert action is the Hellfire missile, fired from UAVs like the

Predator.

Intelligence and accountability

The existence of secret agencies in an open society presents a contradiction and a dilemma for

liberal democracies. In the 1970s, investigators discovered that, in addition to carrying out

assassination plots, the CIA had spied against American citizens protesting the war in Vietnam

(Operation Chaos and Operation HQLINGUAL), the FBI had spied upon and harassed

citizens involved in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War protests (Operation Cointelpro), and

the NSA had intercepted and read the cables of citizens to and from abroad (Operation

Shamrock). In response to these abuses of power, America’s lawmakers created an exceptional

approach to the problem of restraining intelligence agencies, including the establishment of

Senate and House intelligence oversight committees. Since 1975, both branches of government

in the United States have struggled to find the proper balance between legislative supervision

of intelligence, on the one hand, and executive discretion for its effective conduct, on the other

hand. Although the quality of congressional supervision of intelligence has been infinitely

better since 1975, accountability in this domain has suffered from inattention by members of

Congress and a rising level of partisan debates when intelligence does come into focus for the

members.

The Handbook of Intelligence Studies

Here, then, are the main topics addressed in this Handbook, in essays written by many of the top

intelligence authorities in the United States and abroad. Michael Warner, an historian with the

CIA’s Director of National Intelligence, begins Part 1 of the volume with a broad look at

sources and methods for studying intelligence, which is a relatively new field of intellectual

inquiry. Before 1975, the number of reliable books and articles on this subject was few. In the

past three decades, however, the scholarly literature on intelligence has mushroomed, thanks in

large part to a series of congressional and executive-branch inquiries into espionage failures

that unearthed and placed in the public domain a rich lode of new data on the workings of

America’s secret agencies. In the second chapter, James Wirtz of the Naval Postgraduate School

writes about the approach to intelligence studies that he observes in the writings of American

12

LOCH K. JOHNSON

researchers. Next Professor Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones at the University of Edinburgh examines

research specifically related to the FBI. Almost every government activity has an ethical dimen-

sion and Michael Andregg of the University of St Thomas explores the moral implications of

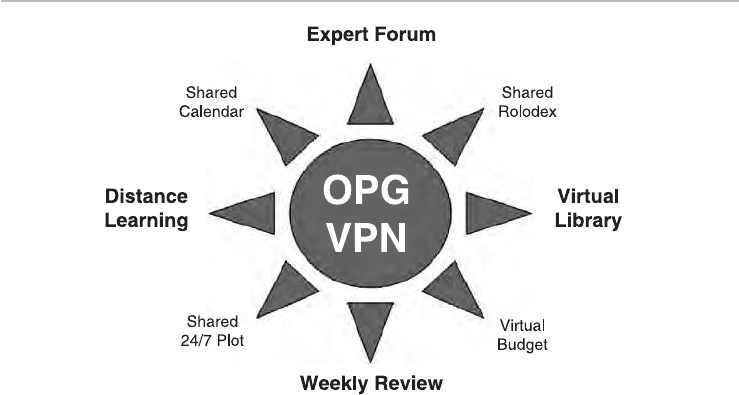

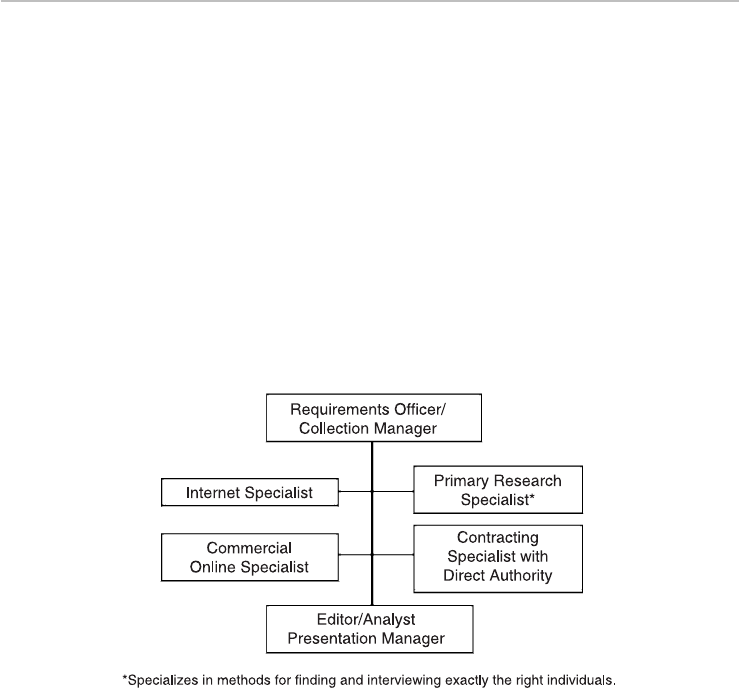

secret intelligence operations in the fourth chapter.