11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

481

Intelligence Analysis and Planning for

Paramilitary Operations

Loch K. Johnson*

I

NTRODUCTION

Paramilitary operations – “PM ops” in American spytalk – may be

defined as secret war-like activities.

1

They are a part of a broader set of

endeavors undertaken by intelligence agencies to manipulate events abroad,

when so ordered by authorities in the executive branch. These activities are

known collectively as “covert action” (CA) or, alternatively, “special

activities,” “the quiet option,” or “the third option” (between diplomacy and

overt military intervention). In addition to PM ops, CA includes secret

political and economic operations, as well as the use of propaganda. Often

used synergically, each form is meant to help nudge the course of history –

insofar as this is possible – in a direction favorable to the United States.

Since the creation of the modern U.S. “intelligence community” by way of

the National Security Act of 1947, PM ops have been conducted by the

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), known by insiders as “The Agency.”

2

This article offers a brief history of America’s paramilitary activities, with

special attention to the relationship between intelligence analysis – the

attempts by the CIA and its fifteen companion agencies

3

to understand

* Regents Professor of International Affairs, University of Georgia. The author

would like to express his appreciation to Louis Fisher for his helpful remarks on an earlier

draft of this essay and to Allison Shelton, a Ph.D. candidate in International Affairs at the

University of Georgia, for her research assistance.

1. See generally WILLIAM J. DAUGHERTY, EXECUTIVE SECRETS: COVERT ACTION & THE

PRESIDENCY (2004); LOCH K. JOHNSON, AMERICA’S SECRET POWER: THE CIA IN A DEMOCRATIC

SOCIETY (1989); JOHN PRADOS, SAFE FOR DEMOCRACY: THE SECRET WARS OF THE CIA (2006);

and G

REGORY F. TREVERTON, COVERT ACTION: THE LIMITS OF INTERVENTION IN THE POSTWAR

WORLD (1987).

2. In recent years, though, some outside observers have expressed concern that the

Department of Defense (DoD) may have slipped through the back door into this sensitive

domain, as part of its war efforts in the Middle East and Southwest Asia in the aftermath of

the 9/11 attacks against the United States. The concern is that DoD may be bypassing the

procedures for accountability currently focused on CIA covert actions. See Jennifer Kibbe,

Covert Action and the Pentagon, in 3 S

TRATEGIC INTELLIGENCE: COVERT ACTION 131-144

(Loch K. Johnson ed., 2007); and John Prados, The Future of Covert Action, in H

ANDBOOK

OF

INTELLIGENCE STUDIES 289-298 (Loch K. Johnson ed., 2007).

3. The other fifteen agencies include eight military organizations embedded within

the DoD: the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, National Reconnaissance Office,

National Security Agency, Defense Intelligence Agency, and the Army, Navy, Air Force and

Marine Intelligence agencies; seven agencies embedded within civilian departments,

including the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Intelligence and the Coast

Guard (both within DHS), Department of Justice (the FBI and the Drug Enforcement

Administration, Department of State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Department of

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

482 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

contemporary world events and forecast how they will unfold – and the use

of paramilitary forces to achieve U.S. foreign policy goals.

I. T

HE METHODS OF CIA PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS

No covert actions have held higher risk or generated more criticism

than “covert” wars (as if any kind of military conflict can be kept secret for

very long). In addition to providing support to groups engaged in

insurgency fighting, the CIA has funded various PM training activities,

including counterterrorism operations. It has also provided military advisers

to pro-American factions fighting against common adversaries, and

transported arms, ammunition, and other military equipment overseas for

distribution to groups allied with U.S. interests, as when the Agency

provided Stinger missiles for Afghan rebels (the Mujahideen) fighting the

Soviet Red Army in the 1980s. Moreover, the CIA has given assistance to

the Pentagon’s unconventional warfare activities, known as “Special

Operations.” The Agency has supplied weapons, as well, to U.S. military

officials for covert sales abroad, including some of the missiles sold to

Tehran by the Department of Defense (DoD) during the Iran-Contra scandal

of 1986-1987. Further, the Agency has trained indigenous military and

police units throughout the developing world. In between covert wars,

America’s PM operatives spend much of their time in training activities at

CIA facilities in the United States. The operatives are responsible, too, for

the maintenance of their paramilitary equipment, and they support selected

CIA intelligence collection operations around the globe.

During the Cold War and since, America’s PM operatives have

disseminated weaponry to allied nations and factions in every corner of the

developing world. The Church Committee, a panel of inquiry into

intelligence activities led by Senator Frank Church, Democrat from Idaho,

in 1975-1976, discovered a wide range of CIA arms shipments to pro-

Western dissidents in a number of small nations. These armaments

included high-powered rifles with telescopes and silencers, suitcase bombs,

fragmentation grenades, rapid-fire weapons, 64-mm antitank rockets, .38

caliber pistols, .30 caliber M-1 carbines, .45-caliber submachine guns, tear-

gas grenades, and enough ammunition to equip several small armies. For

major PM operations, such as the one designed to assist the Mujahideen

fighters in Afghanistan, the amount of ordnance provided by the CIA has

been enormous, dwarfing the arsenals of most countries in the world.

4

Energy, and Department of Treasury. The sixteenth intelligence organization, the CIA,

stands alone as an independent agency.

4. On the findings of the Church Committee related to paramilitary operations, see

F

INAL REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE TO STUDY GOVERNMENTAL OPERATIONS WITH

RESPECT TO INTELLIGENCE ACTIVITIES, S. REP. NO. 94-755 (1976) [hereinafter CHURCH

COMMITTEE]; the Committee’s volume on ALLEGED ASSASSINATION PLOTS INVOLVING

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 483

II. T

HE ASSASSINATION OPTION

An especially controversial aspect of PM ops has been the adoption of

assassination as a method to eliminate dangerous, or, sometimes, merely

annoying, foreign leaders. The CIA’s involvement in murder plots came to

light in 1975. In documents discovered by presidential and congressional

investigators (the Rockefeller Commission, led by Vice President Nelson

Rockefeller, and the Church Committee, respectively), the Agency referred

to its attempts at dispatching selected foreign leaders with such euphemisms

as “termination with extreme prejudice” or “neutralization.” At its

headquarters in Langley, Virginia, the CIA established a “Health Alteration

Committee,” which hatched schemes to eliminate foreign officials. Among

the prime targets for assassination were Fidel Castro of Cuba and Patrice

Lumumba of Congo.

5

A. Targeting Foreign Leaders

During the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, Castro attracted the

full attention of the CIA’s Covert Action Staff (CAS) and its Special

Operations Group (SOG, the home of the Agency’s PM operatives). The

CIA emptied its medicine cabinet of drugs and poisons in various attempts

to kill, or at least debilitate, the Cuban leader. All of these efforts failed,

however, because Castro was elusive and well protected by an elite security

guard trained by the KGB. The Agency then turned to the Mafia for

assistance: Chicago gangster Sam Giancana, the former Cosa Nostra chief

for Cuba, Santo Trafficante, and mobster John Rosselli. These

“godfathers” still had contacts on the island from pre-Castro days when

Havana was a gambling mecca. No doubt assuming the U.S. government

would back away from pending Mafia prosecutions in return for help

against Castro, the crime figures volunteered to assemble teams of Cuban

exiles and other hitmen, then infiltrate them into Cuba. None succeeded.

During the Eisenhower administration and continuing into the Kennedy

years, Lumumba, a dynamic Congolese political leader, came into the

CIA’s cross-hairs as well. From Washington’s point of view, his

transgression – like Castro’s – had been to develop ties with the Soviet

Union. In what some viewed as a zero-sum struggle with the Soviets

FOREIGN LEADERS: AN INTERIM REPORT, S. REP. NO. 94-465 (1975) [hereinafter ALLEGED

ASSASSINATION PLOTS] (subsequently published commercially by W. W. Norton &

Company); and A

NNE KARALEKAS, SUPPLEMENTARY DETAILED STAFF REPORTS ON FOREIGN

AND

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE, S. REP. No. 94-755 (1976). On the supply of weapons to the

Afghan freedom fighters, see S

TEVE COLL, GHOST WARS (2004); and, more generally,

T

HEODORE SHACKLEY, THE THIRD OPTION: AN AMERICAN VIEW OF COUNTERINSURGENCY

(1981).

5. A

LLEGED ASSASSINATION PLOTS, supra note 4.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

484 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

during the Cold War, Lumumba had to go. In 1961, Agency headquarters

forwarded to its chief of station (COS) in Congo an unusual assortment of

items in a diplomatic pouch to achieve this objective: rubber gloves, gauze

masks, a hypodermic syringe, and a toxic substance that would produce a

disease to either kill the victim outright or incapacitate him so severely that

he would be out of commission.

The COS began to plan how he could carry out the specific directions

to inject the toxic material into something that might make it into

Lumumba’s mouth – “into his toothpaste or food,” read the instructions.

6

The station chief informed one of his colleagues to be careful: there was a

“virus” in the CIA’s safe within the U.S. embassy compound at

Leopoldville, the capital of Congo. In dark humor, the recipient of this

hushed disclosure later said to investigators that he “knew it wasn’t for

somebody to get his polio shot up-to-date.”

7

The plan, though, was never

carried out, because the Agency experienced problems in gaining access to

Lumumba. Soon, though, a rival Congo faction, fearful of Lumumba’s

popularity, snuffed out his life before a hastily arranged firing squad. A

recent study suggests that the CIA may have helped to render Lumumba

into the hands of these assassins, achieving its goal after all.

8

The CIA has also been involved in the incapacitation or death of lower-

level officials. The most well known operation of this kind was the

Phoenix Program, carried out by the Agency in South Vietnam as part of

the U.S. war effort during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The operation’s

purpose was to subdue the influence of communists (the Viet Cong, or VC)

in the Vietnamese countryside. According to former Director of Central

Intelligence (DCI) William E. Colby, who led the program for a time as a

young intelligence officer, some twenty thousand VC leaders and

sympathizers were killed. Colby stresses that over 85 percent of these

victims were engaged in military or paramilitary combat against South

Vietnamese or American soldiers.

9

B. A Limited Ban on Assassinations

In 1976, soon after Congress revealed the CIA’s involvement in

international murder plots, President Gerald R. Ford signed an executive

order against this practice. The wording of the order, endorsed by his

successors, reads: “No person employed by or acting on behalf of the

6. Stephen R. Weissman, An Extraordinary Rendition, 25 INTELLIGENCE & NAT’L

SECURITY 198, 205 (2010).

7. A

LLEGED ASSASSINATION PLOTS, supra note 4, at 41 (testimony of Michael

Mulroney, senior CIA officer).

8. Weissman, supra note 6, at 198-222.

9. W

ILLIAM COLBY & PETER FORBATH, HONORABLE MEN: MY LIFE IN THE CIA 272

(1978).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 485

United States Government shall engage in, or conspire to engage in,

assassination.”

10

While honored most of the time, when America is involved

in an authorized overt war – one supported by Congress – the executive

order has been waived. Indeed, former DCI Robert M. Gates observed that

during the first Persian Gulf War in 1991, the White House under President

George H. W. Bush “lit a candle every night hoping Saddam Hussein would

be killed in a bunker” during overt bombings of Baghdad.

11

Most recently, the United States has been involved in authorized overt

warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as against al Qaeda and its Taliban

supporters in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and elsewhere. Again, the executive

order against assassination has been waived in these struggles. Saddam was

regularly a target in the second Persian Gulf War that began in 2003; but, as

in the first Persian Gulf War, he proved to be an elusive target. Eventually,

U.S. troops discovered him hiding in a hole in the ground near his

hometown. He was arrested, tried by an Iraqi tribunal, and hanged – all

with the strong encouragement of the United States under President George

W. Bush. Saddam had ordered an assassination attempt against the

President’s father and mother soon after Iraq’s defeat in the first Persian

Gulf War, when the senior Bushes were visiting Kuwait to celebrate the

victory – an offense not lost on Bush their son. As George W. Bush relates

in a memoir, revenge was part of his motivation for invading Iraq in 2003.

12

Added to the current list of people to be captured or assassinated by the

U.S. military and CIA paramilitary forces are extremist Taliban and al

Qaeda members in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Recently Afghan narcotics

dealers, who are frequently complicit in terrorist activities, have been added

to the targeting list.

13

Since the end of the Cold War, the CIA (in

cooperation with the U.S. Air Force) has developed and fielded its most

deadly paramilitary weapon: unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), such as the

Predator and its more muscular counterpart, the Reaper. Both UAVs, also

known as drones, are armed with surveillance cameras, as well as Hellfire

or other missiles. These systems are controlled remotely from sites in

Afghanistan and Pakistan (for the takeoffs and landings), as well as from

locations in the United States (for the targeting and killing phases of flight).

Cruising at low altitudes, the UAV cameras identify targets, providing

instant “analysis” before the missiles are released by their remote operators

thousands of miles away.

10. Exec. Order No. 12,333, United States Intelligence Activities, 3 C.F.R. 200 (1981).

11. Walter Pincus, Saddam Hussein’s Death Is a Goal, Says Ex-CIA Chief, W

ASH.

P

OST, Feb. 15, 1998, at A36 (quoting former DCI Robert M. Gates).

12. G

EORGE W. BUSH, DECISION POINTS 228-229 (2010).

13. For an account of U.S. drone attacks in the Middle East and Southwest Asia, see

Jane Mayer, The Predator War, N

EW YORKER, Oct. 26, 2009, at 36-45.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

486 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

Targeting mistakes are made. The mistakes are compounded by the fact

that Taliban and al Qaeda terrorists often seek refuge in mosques, schools,

and other locations where innocent civilians may be inadvertently struck by

the UAV missiles, even though the CIA and the Pentagon take pains to

avoid “collateral damage.” Through mid-October of 2010, the drone

program had killed more than 400 al Qaeda militants, with fewer than ten

deaths of noncombatants – at least according to The New York Times,

although other sources believe that the incidental deaths of civilians has

been much higher in number.

14

One thing is certain: innocent civilians

continue to die, and sometimes the drones accidentally strike U.S. soldiers,

too. The drone attacks remain controversial and are unpopular among

many Pakistani citizens, who view them as a manifestation of America’s

violation of their national sovereignty – just as many Pakistanis criticized

the Navy’s surprise commando raid in 2011 that led to the killing of the al

Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, a city near the capital of

Pakistan.

The U.S. military is called upon for some assassination attempts, either

alone or in tandem with CIA operatives. During the Clinton administration,

for instance, the President turned down two proposed attacks by cruise

missiles, ready for firing from U.S. destroyers in the Red Sea and aimed at

bin Laden. In one case, bin Laden was surrounded by several of his wives

and children in an Afghan village, and in another by princes from the

United Arab Emirates (UAE) on a bird-hunting expedition. President

Clinton chose not to risk the deaths of these other individuals in an attack

against bin Laden. On another occasion, the United States fired cruise

missiles from a U.S. Navy cruiser in the Red Sea at a suspected al Qaeda

gathering in the desert near the town of Khost in Paktia Province,

Afghanistan. Bin Laden had already departed, however, before the

warheads struck the encampment.

The al Qaeda leader continued to evade U.S. assassination attempts,

lying low somewhere in the rugged mountains of Western Pakistan (many

experts believed) and protected by Taliban warlords.

15

Then, supported by

fresh intelligence collection and analysis, a Navy Seal Six commando team

stormed a walled, private compound in Abbottabad (just thirty-five miles

from Islamabad), in May 2011, and, under orders from President Barack

Obama, killed bin Laden. The al Qaeda leader had reportedly been holed

up in the Abbottabad hideout for five to six years, underscoring the

14. Unsigned editorial, Lethal Force Under Law, N.Y. TIMES, Oct. 10, 2010, at WK

7; Amitabb Pal, Drone Attacks in Pakistan Counterproductive, T

HE PROGRESSIVE, Apr. 15,

2011, http://www.progressive.org/ap041511.html (arguing that the civilian casualties have

been much higher).

15. On plots against Osama bin Laden, see G

EORGE TENET, AT THE CENTER OF THE

STORM: MY YEARS AT THE CIA (2007); MICHAEL SCHEUER, IMPERIAL HUBRIS (2004); and

Eric Schmitt & Thom Shanker, In Long Pursuit of Bin Laden: The ‘07 Raid That Just

Missed, N.Y.

TIMES, May 6, 2011, at A1.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 487

difficulty of locating terrorists and other criminals on the run in foreign

lands.

16

C. Establishing Hit Lists

Exactly who should be on the PM “kill” list has been a controversial

subject. Originally, the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001

17

stipulated that only

those enemies involved in the 9/11 attacks were legitimate targets for

retaliation. Since then, and without further legislative guidelines, the target

list has widened. For example, a U.S.-born cleric by the name of Anwar al-

Awlaki, reputedly hiding in Yemen where he is considered an al Qaeda

recruiter, has been placed on the CIA assassination list – even though he

has never been convicted in a court of law. Further, it is unclear if he has

actually been involved in plots against the United States. If he has, al-

Awlaki could arguably be a legitimate target; however, if he has limited

himself to making speeches against the United States, al-Awlaki would just

be one of hundreds of radicals in the Middle East and Southwest Asia who

have advocated jihad against Western “infidels.” Regardless, in May 2011

he barely escaped a U.S. drone strike.

18

In an earlier drone attack in 2002, a

Predator missile struck an automobile in a Yemeni desert that carried six

passengers suspected to be al Qaeda affiliates. All were incinerated, and

one turned out to have been an American citizen – again, a person never

brought to trial. Such events raise serious questions about due process, and

the need to establish target bona fides beyond the shadow of a doubt before

Hellfire missiles are fired.

At present, the procedures for developing assassination targeting lists

lack clarity and sufficient oversight. Reportedly, the decision to add to such

lists requires the approval of the U.S. ambassador to the target country, as

well as the approval of the CIA COS, the director of the Agency’s National

Clandestine Service (the SOG’s parent department at the CIA), the Director

of the CIA (D/CIA), and the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), an

16. See Meet the Press, NBC NEWS (May 8, 2011) (reporting that national security

adviser Tom Donilon estimated that bin Laden had been at the compound for “six years”);

60 Minutes, CBS NEWS (May 8, 2011) (interview after the raid reporting that the President

referred to “five or six years”). For an example of reporting on the raid, see Elisabeth

Bumiller, In Bin Laden’s Compound, Seals’ All-Star Team, N.Y.

TIMES, May 5, 2011, at

A14. Even a high-profile fugitive within the United States can remain hidden for a long

time. For example, Eric Rudolph, who set off a bomb at the 1996 Olympic site in Atlanta,

remained on the loose until 2003, when he was accidentally apprehended in North Carolina

– just one state away from the scene of the crime.

17. Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required To

Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-56, 115

Stat. 272.

18. See Ross Douthat, Whose Foreign Policy Is It?, N.Y.

TIMES, May 9, 2011, at A23.

In September 2011, al-Awlaki was killed by a CIA drone.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

488 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

office established in 2004. If the target is an American citizen, like al-

Awlaki, attorneys in the Justice Department must also approve. Further, at

least some of the members of the two congressional intelligence committees

are supposedly briefed on the targeting. Still, critics argue that a more

formal congressional review should take place, and perhaps the courts

should be part of this decision-making process, too. A special court, similar

to the one established in 1978 to review wiretap requests (the Foreign

Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA, Court), could be set up to evaluate

requests for assassinations, especially when American citizens are the

prospective targets.

19

Even when the United States has decided to assassinate a foreign

leader, the task has proved difficult to carry out. Castro reportedly survived

thirty-two attempts against his life by the CIA.

20

Efforts to take out the

warlord General Mohamed Farrah Aidid of Somalia failed during

America’s brief involvement in fighting on the African Horn in 1993, and

Saddam Hussein proved impossible to locate during the 1990s. Osama bin

Laden remained elusive until May of 2011 – almost a decade after the 9/11

attacks. Dictators are paranoid, well guarded, and elusive, as are high-

ranking members of al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

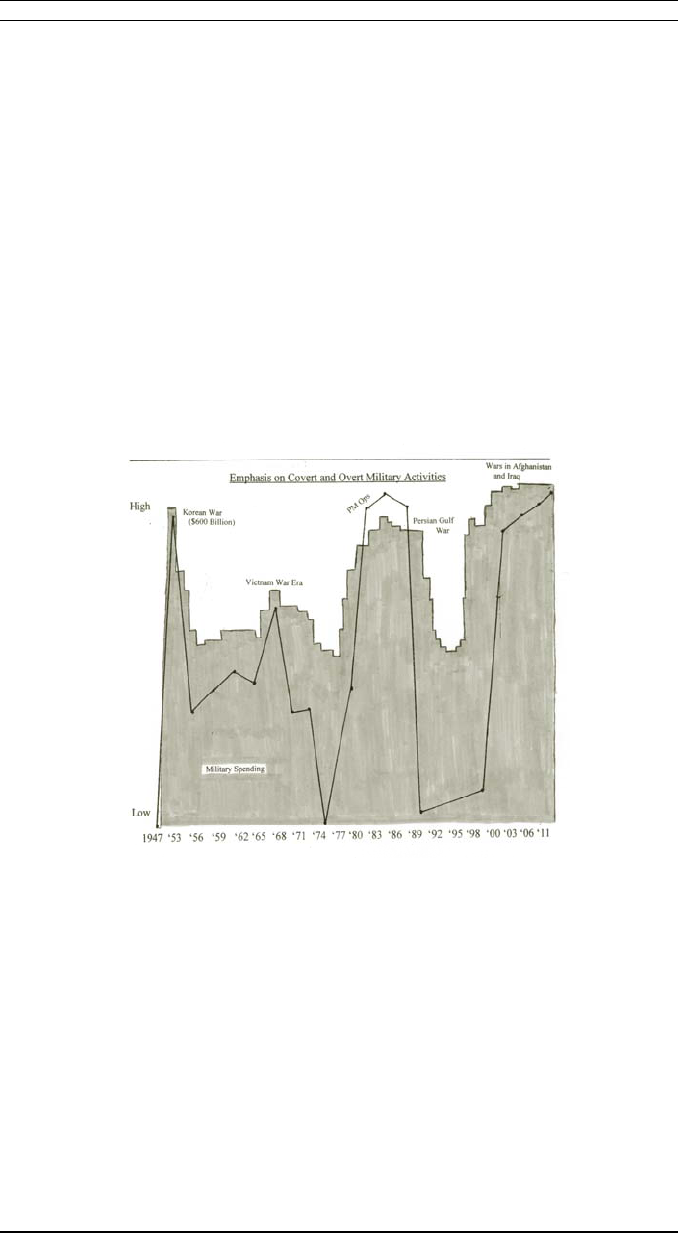

III. T

HE EBB AND FLOW OF PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS

Although PM ops were out of favor with some administrations in the

United States, others have spent enormous sums of money them.

21

As

depicted in Figure 1, support for these activities during the Cold War

accelerated from the very beginning of the CIA’s history in 1947, rising

rapidly from non-existence to high prominence during the Korean War.

22

From 1950-1953, the Agency’s paramilitary capabilities attracted a high

level of attention as a means to support America’s overt warfare on the

Korean Peninsula – the first major use of PM operations by the United

States in the modern era. Henceforth, whenever the United States was

19. This proposal is explored in Lethal Force Under Law, supra note 14.

20. A

DMIRAL STANSFIELD TURNER, BURN BEFORE READING: PRESIDENTS, CIA

DIRECTORS, AND SECRET INTELLIGENCE 98 (2005).

21. For reliable histories of paramilitary operations during the Cold War, see R

HODRI

JEFFREYS-JONES, THE CIA AND AMERICAN DEMOCRACY (1989); and JOHN RANELAGH, THE

AGENCY: THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE CIA (rev. ed., 1987), as well as CHURCH COMMITTEE,

supra note 4; D

AUGHERTY, supra note 1; PRADOS, supra note 1; and TREVERTON, supra note 1.

22. In the figure, the “lows” and “highs” of PM ops represent not precise spending

amounts (data that remain classified), but rather levels of emphasis on this approach adopted

by the White House and the CIA. The estimates about these levels are based on a reading of

the open literature, augmented by the author’s interviews with CIA personnel over the years

since 1975. In the interviews, respondents were asked to assess the degree of emphasis each

Administration placed on PM ops during each of the years since 1947. The trend line is an

approximation, but one endorsed by the hundreds of individuals interviewed, from DCIs to

PM/SOG managers.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 489

involved in overt warfare somewhere in the world, the Agency would be

there as well to back up American troops with PM and other covert actions.

As John Ranelagh reports, covert action funding “increased sixteenfold

between January 1951 and January 1953,” and the number of personnel

assigned to the covert action mission doubled, with most of these resources

dedicated to PM operations.

23

The budget for covert action “skyrocketed,”

according to the Church Committee.

24

FIGURE 1: EBB AND FLOW OF U.S. COVERT AND OVERT MILITARY

ACTIVITIES ABROAD (1947-2011)

Source: This figure includes both expenditure levels for overt military activities (labeled “military

spending”) and the author’s estimates of the government’s emphasis on the use of PM operations (not

actual PM spending levels, which remain classified and would amount to only about 10-to-15 percent of

the overt military expenditures or less, even in peak years). The PM estimates are based on the author’s

interviews with intelligence managers and officers from 1975-2011, along with a study of the literature

cited in the footnotes to this article. The overt military spending levels (adjusted for inflation) are

adapted from Thom Shanker & Christopher Drew, Pentagon Faces New Pressures To Trim Budget,

N.Y.

TIMES, July 23, 2010, at A1.

In 1953, the CIA provided covert assistance to pro-American factions

that brought down the Iranian Prime Minister, Mohammad Mossadeq, and

replaced him with a more pliable leader, the Shah of Iran (Mohammad Reza

23. RANELAGH, supra note 21, at 220.

24. C

HURCH COMMITTEE, supra note 4, at 31.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

490 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

Shah Pahlavi).

25

While propaganda and political operations proved

sufficient to achieve a transfer of power in this instance, PM capabilities

were on stand-by. The next year they would be put to use, as the Agency

succeeded with its plan to frighten the democratically elected Arbenz

government out of office in Guatemala through a combination of

propaganda, political, economic, and small-scale paramilitary operations.

26

These operations in Iran and Guatemala encouraged the Eisenhower

and Kennedy administrations to rely further on the CIA to achieve

American foreign policy victories abroad. William J. Daugherty notes that

the outcomes in Iran and Guatemala “left in their wake an attitude of

hubris” inside the Agency and throughout the Eisenhower administration’s

national security apparatus.

27

Over the next two decades, the CIA

mobilized its paramilitary capabilities in several secret military attacks

against foreign governments, offering support (with mixed degrees of

success) for anti-communist insurgents in such places as the Ukraine,

Poland, Albania, Hungary, Indonesia, Oman, Malaysia, Iraq, the Dominican

Republic, Venezuela, Thailand, Haiti, Greece, Turkey, and Cuba.

A. Vietnam and the Decline of PM Ops

The Bay of Pigs fiasco in Cuba in 1961 created only a short-lived blip

of skepticism about the use of PM ops, before the Kennedy administration

turned again to the Agency for secret assistance in dealing with foreign

headaches.

28

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the CIA and its

recruited mercenaries abroad waged a hidden World War Three against

communist forces, most notably in the jungles of Indochina. For example,

from 1962 to 1968, the CIA backed the Hmung tribesmen

29

in North Laos

during a covert war against the North Vietnamese puppets, the Communist

Pathet Lao.

30

This struggle kept the Pathet Lao preoccupied and away from

killing U.S. troops fighting next door in South Vietnam. The two sides

fought to a draw until the United States withdrew from Laos, at which point

the Pathet Lao decimated the Hmung. The Agency “exfiltrated” a few

fortunate Hmung fighters for resettlement in the United States. Throughout

the war in Vietnam, CIA/PM operatives aided the overt military effort. At

times, covert actions absorbed up to sixty percent of the Agency’s annual

budget, with much of the funding dedicated to paramilitary activities.

31

25. See KERMIT ROOSEVELT, COUNTERCOUP: THE STRUGGLE FOR THE CONTROL OF

IRAN (1981).

26. See D

AVID WISE & THOMAS ROSS, THE INVISIBLE GOVERNMENT (1964).

27. DAUGHERTY, supra note 1, at 140.

28. P

ETER WYDEN, BAY OF PIGS: THE UNTOLD STORY (1979).

29. “Hmung” is pronounced with a silent “h” and sometimes referred to as the Meo.

30. See C

OLBY & FORBATH, supra note 9, at 191-202.

31. Author’s interview with a senior CIA manager, Washington, D.C. (Feb. 18, 1980).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 491

A precipitous slide downward for PM ops occurred in the early 1970s,

induced by a souring on the war in Vietnam, along with government

spending cuts promulgated by the Nixon administration, tentative overtures

of détente with the Soviet Union, and a domestic spy scandal in 1975 that

revealed the CIA’s assassinations plots and its attacks against the

democratically elected government of Chile (the Allende regime). These

revelations, especially from the Church Committee, raised doubts among

the American people and their representatives in Congress about the

propriety and value of PM and other covert actions. Public reaction

brought this approach to American foreign policy “to a screeching halt,”

recalls a senior CIA official.

32

Covert action across the board fell into a temporary decline during the

Ford and the early Carter years, but began to turn upward again during

latter stages of the Carter administration – ironically, since President

Jimmy Carter had campaigned in 1976 against the use of “dirty tricks” by

the Agency. The chief catalyst for Carter’s turn-around was the Soviet

invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

B. The Golden Age of PM Ops

Under President Ronald Reagan, the CIA pursued major paramilitary

operations in a number of nations around the world, but with special

emphasis in Nicaragua and Afghanistan – indeed, the second most

extensive use of paramilitary operations in the nation’s history, surpassing

its emphasis during the Korean War. The Nicaraguan involvement ended in

the Iran-Contra scandal in 1986-1987, while, in sharp contrast, the

Agency’s support of Mujahideen in Afghanistan during the Reagan

administration is considered one of the glory moments in the CIA’s

history.

33

The Agency provided advanced shoulder-held missiles to the

Mujahideen, which helped turn the tide of the war and send the Red Army

into retreat. Most recently, PM ops have reached a third high-point in

emphasis, this time in support of America’s overt wars in Iraq and

Afghanistan, along with operations directed against al Qaeda and other

terrorist organizations, and in support of various liberation movements in

North Africa. As displayed in Figure 1, most of the time America’s

emphasis on CIA/PM operations has been in support of U.S. overt military

intervention overseas. The Reagan administration, however, provided the

32. Author’s interview with a senior CIA officer, Washington, D.C. (Oct. 10, 1980).

33. On the Iran-Contra Affair, see SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON SECRET MILITARY

ASSISTANCE TO IRAN AND THE NICARAGUAN OPPOSITION and HOUSE SELECT COMMITTEE TO

INVESTIGATE COVERT ARMS TRANSACTIONS WITH IRAN, HEARINGS AND FINAL REPORT, S.

REP. NO. 100-216 and H.R. REP. NO. 100-433 (1987); on the PM ops in Afghanistan during

the 1980s, see C

OLL, supra note 4; and GEORGE CRILE, CHARLIE WILSON’S WAR (2003).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

492 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

most conspicuous exception to this rule: during the 1980s, the United States

avoided major overt warfare but PM ops enjoyed a period of maximum use

– the Golden Age of CIA paramilitary operations – against adversaries in

Nicaragua and Afghanistan.

John Deutch, one of President Clinton’s DCIs, observed in 1995 that

“since the public controversies of the eighties over Iran-Contra and

activities in Central America, we have greatly reduced our capability to

engage in covert action.”

34

With the election of George W. Bush, covert

action at first remained at a modest level – until the 9/11 attacks. Then,

with three wars being fought simultaneously by the United States (in Iraq

and Afghanistan, and against global terrorism), PM ops enjoyed a dramatic

resurgence, directed chiefly against targets in the Middle East and

Southwest Asia. This rejuvenation brought reliance on paramilitary

activities up to the levels recorded during the earlier historical high-points,

in Korea from 1950 to 1953, and during the Reagan administration’s covert

involvement in Nicaragua and Afghanistan. President Obama has

maintained the high level of emphasis on the PM ops established by the

second Bush administration, even escalating the frequency of Predator and

Reaper attacks against the Taliban and al Qaeda in Southwest Asia, as well

as authorizing covert action in support of rebels attempting to topple the

Libyan regime of Colonel Muammar Gadhafi.

35

IV. PM

OPS AND THE ANALYTIC SIDE OF INTELLIGENCE

The primary mission of the CIA and its companion agencies is not PM

activities or any other form of covert action; it is to acquire information

about world affairs (“collection,” in spy vernacular) and then to make sense

of it (“analysis”), so that decision-makers will have a better understanding

of the global situations they face.

36

Further, decision-makers hope to have

accurate, timely information and prescient analysis to enhance the chances

for PM successes when this tool of foreign policy is adopted. Paramilitary

operations, though, bump up against the same dilemma that confronts every

effort to predict how a foreign policy initiative will play out in the world:

namely, the inability of anyone – intelligence analyst, academic expert,

34. John Deutch, DCI, The Future of US Intelligence: Charting a Course for Change,

Address at the National Press Club (Sept. 12, 1995).

35. See, for example, Mark Mazzetti & Eric Schmitt, C.I.A. Intensifies Drone

Campaign Within Pakistan, N.Y.

TIMES, Sept. 28, 2010, at A1; and, with respect to Libya,

Mark Mazzetti & Eric Schmitt, Rebels Are Retreating: C.I.A. Spies Aiding Airstrikes and

Assessing Qaddafi’s Foes, N.Y.

TIMES, Mar. 31, 2011, at A1. Whether the covert action

authority included PM ops in support of the rebels remained unspecified in The Times

reporting.

36. L

OCH K. JOHNSON, NATIONAL SECURITY INTELLIGENCE (2011); and MARK M.

LOWENTHAL, INTELLIGENCE: FROM SECRETS TO POLICY (4th ed. 2009).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 493

think-tank specialist, or media commentator – to forecast the future with

confidence.

A. The Limits of Analysis

“[T]he CIA Directorate of Science and Technology has not yet

developed a crystal ball[,]” Senator Church observed in 1975, adding that

“ . . . [t]hough the CIA did give an exact warning of the date last year when

Turkey would invade Cyprus [in 1974], such precision will be rare. Simply

too many unpredictable factors enter into most situations. The intrinsic

element of caprice in the affairs of men and nations is the hair shirt of the

intelligence estimator.”

37

When it comes to predictions, intelligence scholar

Richard K. Betts stresses that “some incidence of failure [is] inevitable.”

He urges a higher “tolerance for disaster.”

38

The bottom line: accurate,

timely information about the activities of America’s adversaries is often

scarce or ambiguous, with much more “noise” than “signal” in the mix of

gathered intelligence. Further, the situation in question may be fluid and

rapidly changing. Advises former intelligence officer Arthur S. Hulnick:

“Policy makers may have to accept the fact that all intelligence estimators

can really hope to do is to give them guidelines or scenarios to support

policy discussion, and not the predictions they so badly want and expect

from intelligence.”

39

This realistic sense of limitations is distressing news for Presidents and

cabinet secretaries who seek clear-cut answers as to whether PM ops will

succeed, not just hunches and hypotheses. Nevertheless, such is the reality

of intelligence. It bears repeating, though, that having intelligence agencies

studying world events and conditions is, however limited the results, still

better than operating blindly. As a well regarded CIA analyst has put it:

“There is no substitute for the depth, imaginativeness, and ‘feel’ which

experienced top estimators can bring to these semi-unknowable

questions.”

40

37. 121 CONG. REC. S35786 (1975) (speech of Sen. Church).

38. Richard K. Betts, Analysis, War and Decision: Why Intelligence Failures Are

Inevitable, 31 W

ORLD POLITICS 61, 87, 89 (1978). See also RICHARD K. BETTS, ENEMIES OF

INTELLIGENCE: KNOWLEDGE & POWER IN AMERICAN NATIONAL SECURITY (2007).

39. Arthur S. Hulnick, Book Review, 14 C

ONFLICT QUARTERLY 72, 74 (1994)

(reviewing H

AROLD P. FORD, ESTIMATIVE INTELLIGENCE: THE PURPOSES AND PROBLEMS OF

NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATING (1993)).

40. H

AROLD P. FORD, ESTIMATIVE INTELLIGENCE: THE PURPOSES AND PROBLEMS OF

NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATING 208 (revised ed. 1993).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

494 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

B. Mysteries and Secrets

Those who are engaged in the planning of PM ops will sometimes

benefit from wise intelligence analysis, but no one can ensure the success of

secretive warfare in addressing America’s foreign policy challenges abroad.

An important distinction made by intelligence practitioners is the difference

between “mysteries” and “secrets.” Mysteries are subjects that a nation

would like to know about in the world, but that are difficult to fathom in

light of the limited capacity of human beings to anticipate the course of

history - say, the question of who might be the next leader of Germany or

Libya, or whether Pakistan will be able to survive the presence of extremist

Taliban insurgents and al Qaeda terrorists based inside its borders. In

contrast, secrets are more susceptible to discovery and comprehension,

although even they may be difficult to uncover, such as the number of

nuclear warheads in China, the identity of Russian agents who have

infiltrated NATO, or the efficiencies of North Korean rocket fuel.

With the right spy in the right place, with surveillance satellites in the

proper orbit, or with reconnaissance aircraft that can penetrate enemy

airspace, a nation might be able to unveil secrets; but, in the case of

mysteries, leaders must rely largely on the thoughtful assessments of

intelligence analysts about the contours of an answer, based on as much

empirical evidence as can be found in open sources or through espionage.

Prudent nations attempt to ferret out secrets, but they can only ponder

mysteries – including how well CIA foreign mercenaries, like the Hmung,

will carry out PM operations under conditions of great adversity.

C. Intentions and Capabilities

Vexing, too, is the analytic task of trying to probe the intentions of

foreign adversaries, not only their military capabilities. One can use

satellites and reconnaissance aircraft to ascertain the number of enemy

soldiers, tanks, and missiles in the field (“bean counting”); however, what

are the enemy’s plans for the use of these weapons – his intentions? Here

the use of human agents (“humint”) can trump the value of spy machines.

A well-placed agent (“asset”) might be in a position to ask a foreign leader:

“What will you do if the United States does X?” As former CIA officer

John Millis has written: “Humint can shake the intelligence apple from the

tree, where other intelligence collection techniques must wait for the apple

to fall.”

41

Successful PM ops may well depend on good analysis; but,

41. LOCH K. JOHNSON, THE THREAT ON THE HORIZON: AN INSIDE ACCOUNT OF

AMERICA’S SEARCH FOR SECURITY AFTER THE COLD WAR (2011) (citing John I. Millis, Why

Spy? 5 (Unpublished Working Paper, June 1995)). See also John I. Millis, Staff Director of

the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, Address at the Central Intelligence

Retirees Association (Oct. 5, 1998).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 495

beforehand, good analysis requires reliable humint and technical collection

capabilities (“techint”).

D. Some Case Examples

A look at a few cases provides a sense of how well, or how poorly,

analysis has managed to inform significant CIA paramilitary activities over

the years.

1. Korea, 1950

Although Agency analysts reported on the mustering of North Korean

troops along the North-South border that belted the Korean Peninsula, they

did not predict the North Korean invasion into the South on June 25, 1950.

Nor did they anticipate, once war was under way, the duration of the

conflict or its eventual stalemate at the 38th parallel.

42

Whether the CIA

warned the U.S. military in Korea that China would intervene remains a

controversial matter. The American commander in the theater, the

imperious General Douglas MacArthur, claimed that the Agency had

reassured him that the Chinese would stay out of the war. In direct

contradiction, President Harry Truman said publicly in November 1950 that

the CIA had warned of a Chinese march into Korea across the frozen Yalu

River.

43

Either way, Agency PM operatives were largely on their own in

support of overt U.S. fighting during this period, with little reliable strategic

analysis from the CIA’s fledgling Directorate of Intelligence (DI, home of

the Agency’s analysts).

2. Guatemala, 1954

Analysts in this instance provided reliable insights into the plight faced

by the United Fruit Company, an American corporation, in Guatemala. As

predicted, it suffered confiscation in 1953 at the hands of a reform-minded,

democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz. Based on the Agency’s

analytic reports and his own hunches, Allen Dulles, the DCI at the time,

figured that a paramilitary operation had only about a 40 percent chance of

success.

44

Policymakers in the Eisenhower administration were filled with

optimism about the CIA’s capabilities, however, in the wake of the

Agency’s bloodless covert action in Iran (sans PM ops) that managed to

overthrow the prime minister in 1953, allowing British and U.S.

intelligence to install their own choice of leaders, the Shah. Hoping for a

42. RANELAGH, supra note 21, at 186-189.

43. Id. at 215 (relying on The New York Times reporting at the time).

44. Id. at 266.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

496 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

repeat performance, the Administration green-lit the Guatemala operation,

despite Dulles’s unfavorable betting odds. As it turned out, the regime

quickly cratered, as the CIA’s covert action staff spread effective

propaganda against the Arbenz regime, while its paramilitary branch fielded

a limited number of mercenaries to scare the President and killed a few

palace resisters.

45

In the Guatemala case, analysis took a backseat to the

reigning brio at the time that favored covert action as a means for ridding

the world of left-wing leaders insufficiently subservient to Western anti-

communist expectations. The United Fruit Company was no doubt pleased

at the outcome at the time – a result also sought by the U.S. Congress; but

the impoverished citizens of that nation had to endure repressive regimes

after the CIA intervention. As the prominent journalist Anthony Lewis

concludes, “The coup began a long national descent into savagery.”

46

3. Cuba, 1961

A lack of communication between PM operatives and DI analysts left

the former with an unrealistic impression of how easy a paramilitary

invasion of Cuba would be. The failed Bay of Pigs operation might never

have been launched in the first place, had President Kennedy or PM

managers been informed about the deep-seated reservations of Agency

analysts toward any attempts to oust Castro – so popular in Cuba – by a PM

invasion operation. Analysts could have been pivotal in this case, but they

were ignored.

47

4. Vietnam, 1964-1973

During the Vietnam War, CIA analysts warned the Johnson White

House about the limited opportunities for military success, overt or covert,

in Indochina. The Administration discounted these warnings, however,

because the President was unwilling to face the prospect of an American

military defeat.

48

As officials in the Administration shunted aside the

perceptive assessments of the CIA’s Vietnam analysts in favor of self-

delusion, PM operatives found themselves caught in the same downward

spiral of defeat that seized America’s overt forces.

45. WISE & ROSS, supra note 26.

46. Anthony Lewis, Costs of the C.I.A, N.Y.

TIMES, Apr. 25, 1997, at A27.

47. THOMAS POWERS, THE MAN WHO KEPT THE SECRETS: RICHARD HELMS AND THE

CIA 115-116 (1979); WYDEN, supra note 28, at 99.

48. Thomas L. Hughes, The Power To Speak and the Power To Listen: Reflections on

Bureaucratic Politics and a Recommendation on Information Flows, in S

ECRECY AND

FOREIGN POLICY, 28-37 (Thomas Franck & Edward Weisband eds., 1974); FORD, supra note

40.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 497

5. Iran-Contra, 1980s

William J. Casey, DCI for the Reagan administration, cut out Agency

analysts from the planning for the highly secretive, extra-governmental

Contra operations in Nicaragua. The controversial PM ops went forward

without the participation of analysts in the CIA’s DI, resulting in the worst

paramilitary disgrace in the Agency’s history.

49

6. Afghanistan, 1980s

This PM op was successful, over the short term at least; it helped drive

the Soviet Red Army out of Afghanistan. Over the long term, however, it

led to the rise of the Taliban regime, which gave safe haven to al Qaeda at

the time of its 9/11 attacks against the United States. The PM operation

against the Red Army was driven chiefly by a senior lawmaker in the

House of Representatives, Charlie Wilson, Democrat of Texas, in cahoots

with a Special Operations officer who believed it would be possible to drive

the Soviet Army out of Afghanistan if only the CIA would vigorously assist

the Mujahideen with paramilitary support. Wilson managed to convince

DCI Casey and the Reagan White House to back a covert war against the

Soviets in Afghanistan, as skeptical analysts from the DI stood by largely

on the sidelines.

50

7. Afghanistan, 2001-2002

Two decades later, a PM endeavor to rout the Taliban regime in

Afghanistan and capture or kill al Qaeda operatives worked effectively. It

was based in part on analyses prepared by the DI and military intelligence

units that indicated how a combination of SOG operatives, DoD Special

Forces, overt B-52 air support, and the recruitment of indigenous Northern

Alliance anti-Taliban forces could result in a routing of the Taliban

regime.

51

Here is a model of cooperation between analysts and operatives

that led to an excellent outcome – that is, until the second Bush

administration shifted its attention to war-making against Iraq rather than

concentrating on closing the noose around fleeing Taliban and al Qaeda

warriors in Afghanistan.

49. WILLIAM S. COHEN & GEORGE J. MITCHELL, MEN OF ZEAL: A CANDID INSIDE

STORY OF THE IRAN-CONTRA HEARINGS (1988); HEARINGS AND FINAL REPORT, S. REPT. NO.

100-216 and H. R. REPT. NO. 100-433, supra note 33.

50. C

OLL, supra note 4; CRILE, supra note 33.

51. B

OB WOODWARD, BUSH AT WAR (2002).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

498 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

8. Iraq, 2003

Paramilitary support for America’s overt invasion of Iraq in 2003

helped to bring about a quick battlefield victory for U.S. overt forces, as

anticipated by CIA analysts. The Agency’s analysts failed, however, to

assess correctly how difficult the consolidation of U.S. control in Baghdad

would be after the initial success – significantly underestimating the long-

lasting opposition of insurgents, whom the Agency’s PM officers and assets

had to fight in tandem with U.S. uniformed soldiers for the next seven

years.

52

Even more significantly, most analysts in the intelligence community –

with the exceptions of some in Air Force Intelligence, in the State

Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR), and in the

intelligence unit inside the Energy Department – wrongly accepted the

hypothesis about the existence of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction

(WMD). This acceptance contributed to the decision of the second Bush

administration to engage in overt and covert warfare against the Saddam

Hussein regime in March of 2003.

53

Thirteen of the sixteen U.S.

intelligence agencies went along with the notion, for example, that

aluminum tubing spotted in Iraq was for the construction of a nuclear

centrifuge, rather than for the launching of short-range conventional

rockets, and that mobile vans were biological-weapons labs, rather than (as

it turned out) merely sites where hydrogen was produced for inflating

weather balloons.

54

The Bush administration may well have unleashed the

Pentagon and CIA Special Operations officers against Iraq anyway, for a

number of reasons beyond the scope of this essay, but the faulty analysis

provided the White House with a compelling portrait of consensus among

intelligence analysts that Saddam Hussein was in hot pursuit of a WMD

program.

55

The tragedy of these analytic errors is that they fueled the Bush

administration’s rush to war in Iraq, diverting America’s attention from the

52. ROBERT JERVIS, WHY INTELLIGENCE FAILS: LESSONS FROM THE IRANIAN REVOLUTION

AND THE

IRAQ WAR (2010); BOB WOODWARD, PLAN OF ATTACK (2004).

53. This is not to say that intelligence analysts alone got it wrong in Iraq; some

academics, think tank experts, and media commentators also assumed the existence of a

WMD program. Still, the fact that two of America’s top allies, Germany and France,

opposed a Western invasion until more information could be gathered about the WMD threat

in Iraq should have given analysts – inside and outside the government – greater pause.

54. See J

ERVIS, supra note 52; and LOCH K. JOHNSON, THE THREAT ON THE HORIZON:

AN INSIDE ACCOUNT OF AMERICA’S SEARCH FOR SECURITY AFTER THE COLD WAR (2011).

55. As analyst-in-chief for the intelligence community at the time, DCI George Tenet

could have done much more to emphasize to the President the importance of considering the

viewpoints of the dissenting agencies – especially the Energy Department’s intelligence unit,

with its deep expertise on matters related to the construction of nuclear weapons. The

Executive Summary of the 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Iraqi WMDs failed

even to mention the dissent.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 499

mission of tracking down the al Qaeda perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks

against the United States.

9. Assassination Plots, 1959-2011

The CIA’s managers banned analysts from deliberations on the

assassination plots hatched during the Eisenhower and Kennedy

administrations. Later, during the war in Vietnam, DI estimates that

underlay the Phoenix Program tended to inflate the significance of

eliminating suspected VC leaders and sympathizers. The Program killed

thousands of VC, but the war was still lost. In the case of al Qaeda,

analysis pointed to opportunities where bin Laden might be killed; but, in

the attempts that took place before the May 2011 success, the estimates

were either wrong about his location, as in the Khost miss, or the plans for

assassination were rejected by either President Clinton or U.S. field

commanders under Presidents Clinton and George W. Bush on ethical

grounds (a dimension to the plots largely ignored by analysts on the CIA’s

bin Laden Unit in their eagerness to eliminate the al Qaeda chief). As for

the UAV missile attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan in recent years,

collectors and analysts have sometimes wrongly identified targets, leading

to the death of noncombatants and a substantial setback in U.S. relations

within the region. Improvements in collection and analysis, however, have

reportedly diminished the number of targeting mistakes in 2011.

56

The assassination attempts against bin Laden illustrate the complex

relationship between intelligence analysis, on the one hand, and

paramilitary operations, on the other hand. In the murky world of

counterterrorism where accurate, actionable intelligence is rare, analysts are

often divided over what assessments they should pass on to decision-

makers. For example, in the lead-up to a 2007 plan aimed at killing bin

Laden during an uncommon gathering of al Qaeda leaders in Tora Bora,

Afghanistan, CIA and other U.S. intelligence analysts (as well as the

Afghanistan intelligence service allied with the United States) were of two

minds about whether bin Laden would actually attend the meeting. While

the Pentagon readied military force to wipe out the terrorists (including

plans for the use of widespread “carpet bombing” of the meeting site by B-

2 Stealth aircraft), intelligence analysts continued to debate the likelihood

of a bin Laden presence. Some believed he would be too cautious to attend.

Others concluded that he would take the chance, since Tora Bora was close

to his suspected place of refuge somewhere in the mountains just across the

border in Pakistan, and, moreover, here was an irresistible opportunity for

bin Laden to rally al Qaeda lieutenants for a new wave of suicide attacks

56. Mazzetti & Schmitt, C.I.A. Intensifies Drone Campaign, supra note 35.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

500 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

against the West. As the analysts continued to argue about the possibilities,

Admiral William J. Fallon decided to call off the mission out of concern for

the risks it posed to civilians in the target area.

57

The decision to attempt another assassination attempt against bin Laden

in 2011 was replete with uncertainty as well. President Obama recalls that

the intelligence regarding whether or not the al Qaeda leader was really in

the Abbottabad compound – though impressive in many details (an

“incredible job,” said the President) – nonetheless remained in the category

of “circumstantial evidence.” The President added that on the eve of the

commando raid, the intelligence was, at best, “still a 55/45 situation” in

favor of finding bin Laden in the compound, and his National Security

Adviser provided an even lower figure, saying that the intelligence was in

the realm of “50/50.”

58

The intelligence analysis, based on human and

technical sources, proved highly accurate and the mission resulted in

America’s greatest success in the struggle against global terrorism since the

9/11 attacks.

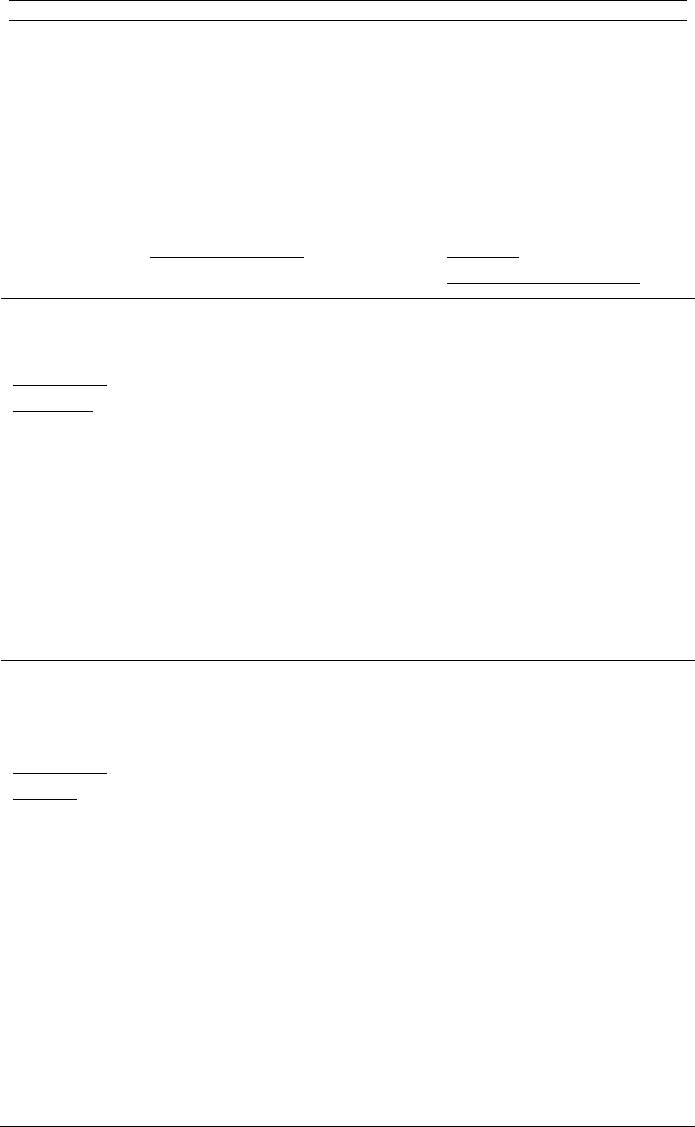

A summary of these important cases is presented in Figure 2. The

pattern suggests that, in the absence of participation by analysts, PM

operations have been prone to failure, as shown by the outcomes in Cuba,

the Contra operations in Nicaragua, and the assassination plots of the 1960s

– the three most conspicuous PM failures in the CIA’s history. Failure

occurred, too, when analysts were allowed to weigh in, but their

assessments were dismissed, as with the Vietnam War experience. Failure

also occurred, further, when analytic guidance was provided and accepted,

as in the case of the Agency’s optimistic estimate about the lack of a lasting

insurgency opposition to American uniformed forces after the initial Iraqi

invasion in 2003.

57. See Schmitt & Shanker, supra note 15.

58. See 60 Minutes, supra note 16; Meet the Press, supra note 16. Defense Secretary

Robert M. Gates, a former Intelligence Director, offered similar testimony on 60 Minutes on

May 15, 2011.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 501

F

IGURE 2: ROLE OF INTELLIGENCE ANALYSIS AND PM OPERATIONAL

FAILURE OR SUCCESS, CASE EXAMPLES (1947-2011)

Provided Guidance Provided

No, or Faulty, Guidance

Operational

Successes

Guatemala, 1954 (guidance

rejected); Afghanistan, 1980s

(guidance rejected); Afghanistan,

2001-2002 (guidance accepted);

Iraq invasion plans, 2003

(guidance accepted); UAV

attacks in SW Asia, 2010 (as

guidance improved, it was

accepted); successful

assassination of bin Laden, 2011

(guidance accepted, though with

considerable analytic uncertainty

still present)

Korea, 1950 (no guidance)

Operational

Failures

Vietnam, 1965-1973 (guidance

rejected); Iraq, 2003: WMDs, as

well as post-invasion

Invasion insurgents (guidance

accepted)

Cuba, 1961 (no guidance);

Contras, 1980s (no

guidance); assassination

plots, Castro/Lumumba (no

guidance); Phoenix (faulty

guidance); early

assassination plots, bin

Laden (faculty guidance);

UAV attacks in SW Asia,

2001-2009, a case of uneven

guidance accepted with some

operational successes and

some failures – with the

failures (civilian casualties)

especially harmful in terms

of local opinion regarding

America’s interventions

On the success side, sometimes PM ops have worked out well despite

skepticism from analysts. For example, the CIA’s Special Operations

managers rejected cautionary analytic estimates and, nonetheless, PM

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

502 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

operations succeeded in Guatemala in 1954 and in Afghanistan in the

1980s. Some degree of success came in the Korean War – the communists

were eventually stopped in their attempt to take over the entire Korean

Peninsula – without the benefit of analytic warnings about the invasion

intentions of the North Koreans in 1950. On other occasions, analysts and

PM operatives have been aligned. Analysis predicted battlefield success,

and success came, in Afghanistan during 2001-2002, as well as with the

initial Iraqi invasion in 2003 – although analysts were disastrously wrong in

suspecting the presence of WMD in Iraq. Further, in the waning months of

2010 and into 2011, analysts have aided PM ops with more accurate UAV

targeting of Islamic extremists in Southwest Asia. And, with the

pinpointing of bin Laden’s location at the Abbottabad compound in 2011,

intelligence collectors and analysts, along with the Navy Seals team that

followed their guidance, enjoyed a remarkable success.

The outcomes in this brief survey of key PM cases are mixed;

nevertheless, as an overall conclusion, one can say that the incidence of

paramilitary failures might well have been lessened with a closer working

relationship between intelligence analysts and operatives. The chronic

dismissal of analysts from PM deliberations over the decades is cause for

concern, even if analysts sometimes produce flawed estimates. Recently,

with respect to U.S. intervention in Libya in 2011, the Obama

Administration reportedly authorized covert action in support of rebel

actions against Colonel Gadhafi, even though CIA analysts had little

information about the composition and motivation of the rebellious

factions.

59

V.

CO-LOCATION AND OTHER REFORMS

Within the human limitations faced by collectors and analysts,

intelligence managers have attempted to make some improvements in the

capacity of analysis to inform paramilitary planning. Reformers have long

believed that analysis could be enhanced by having a closer working

relationship between the Agency’s PM and other CA operatives (the doers)

and its analysts (the thinkers). The operatives enjoy “ground truth” about

foreign nations, since that is where they serve under official or non-official

cover. This gives them a certain inside knowledge, from cafe society to the

nuances of local slang. The analysts are experts about foreign countries,

too, and they also travel abroad, albeit for shorter periods of time. Their

primary knowledge comes from study; they typically have Ph.D.s that

reflect advanced book-learning and research on international affairs.

Though starkly different in their career paths and daily experiences, both

groups bring something to the table when a specific nation or region is the

59. Mazzetti & Schmitt, Rebels Are Retreating, supra note 35.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 503

focus of U.S. paramilitary attention. Yet, traditionally, operatives on

rotation back to Washington and in-house analysts have had offices in

separate locations at Agency headquarters, behind doors with combination

locks that bar entry to “outsiders.” This internal “stovepiping” at the CIA

can have unfortunate consequences.

For example, in the planning that went into the Bay of Pigs invasion,

PM operatives were enthusiastic and confident about the chances for

overthrowing Castro; the people of Cuba, they calculated, would rise up

against the dictator once the Agency landed its paramilitary force on the

island beaches. In another part of the CIA, however, analysts with

expertise on Cuba understood that an uprising was highly unlikely, given

Castro’s tight grip on the nation and his widespread popularity. As the

analysts spelled out in a Special National Intelligence Estimate (SNIE) in

December of 1960, the people of Cuba venerated their leader and would

fight an invasion force door-to-door in Havana and across the island. The

PM managers at the CIA could have benefitted significantly from rubbing

shoulders with their colleagues in the DI, receiving a stronger dose of

realism in their paramilitary planning – or perhaps ending it altogether – but

they were not made aware of the DI’s views. Nor was President Kennedy

made aware of the DI’s views on the remote chances for a PM success in

Cuba. The head of the Bay of Pigs planning, Richard M. Bissell, Jr., had

some corridor knowledge of the skeptical SNIE, but did not take it

seriously, and he never brought its findings to the attention of the White

House. Bissell didn’t want naysayers interrupting his plans to rid President

Kennedy of the Castro irritant, nor did he want obstacles in the way of his

own personal career ambitions to become Director of Central Intelligence

by demonstrating to the President his skill in toppling the Cuban dictator.

60

Yet, the end result of the operation was to ruin Bissell’s meteoric

intelligence career.

Aware of the physical and cultural distance between CA operatives and

intelligence analysts, John Deutch took steps as DCI in 1995 to improve

their cooperation at Agency headquarters. He moved several officers from

both camps into common quarters, where they sat cheek by jowl with one

another. This experience in “co-location” has been uneven. Sometimes the

doers and the thinkers have displayed personality clashes that get in the way

of sharing information. On other occasions, however, the experiment has

led to the achievement of its goal of blending in-country experience with

library learning to provide intelligence planners and policymakers with

deeper insights into world affairs. In 2009, CIA Director Leon Panetta

announced that there would be “more co-location of analysts and operators

60. See POWERS, supra note 47, at 111, 115-116; ARTHUR M. SCHLESINGER, JR.,

ROBERT KENNEDY AND HIS TIMES 453 (1978); and, generally, WYDEN, supra note 28.

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

504 JOURNAL OF NATIONAL SECURITY LAW & POLICY [Vol. 5:481

at home and abroad” in the coming years, noting further that greater fusion

of the two groups “has been key to victories in counterterrorism and

counterproliferation.”

61

In 2010, Panetta unveiled the formation of a CIA

Counterproliferation Center to combat the global spread of WMD. In the

Center, which would report to Panetta as well as to a director for the

National Counterproliferation Center, operatives and analysts would work

side by side in the spirit of co-location.

62

As a further means for improving intelligence analysis and increasing

its usefulness for guiding PM and other covert actions, a wide range of

reforms have been introduced at the Agency in recent years. Among them:

taking steps to involve analysts throughout the intelligence community in

PM planning, not just DI analysts, and employing “blue team” and “red

team” drills designed to provide outside critiques of assessments produced

by analysts inside the intelligence community.

63

Intelligence managers are

also aggressively seeking to improve foreign language skills throughout the

sixteen agencies, to develop more spy rings in the Middle East and

Southwest Asia, and to place more U.S. intelligence officers under non-

official cover outside the U.S. embassies overseas in order to gain a better

understanding of local cultures and an improved chance of recruiting agents

who can infiltrate al Qaeda and other key targets. Most important, though,

will be the attitudes of PM managers toward the value of including analysts

in their planning stage: a willingness to consult with top intelligence experts

on foreign nations and organizations before the launching of a paramilitary

operation.

C

ONCLUSION

Frequently, PM activities have moved forward without much, or any,

guidance from intelligence analysts. These operations have sometimes

succeeded nonetheless, as in Afghanistan during the 1980s, and sometimes

they have failed, as with the Bay of Pigs. On other occasions, analysis has

informed PM activities. Again, at times the result has been some degree of

short-term success, as with Guatemala in 1954, or failure, as in Vietnam,

when policymakers rejected the DI’s guidance. Now and then, analysts and

operatives have worked closely together in the spirit of co-location to

achieve a smooth blend of thoughtful guidance that has led to stunningly

effective results on the battlefield. Afghanistan in 2001-2002 is the classic

illustration. Co-location seems to be a promising concept. This experiment

61. Quoted by Greg Miller, CIA Is Moving More Analysts from Langley to Global

Posts, W

ASH. POST, Apr. 30, 2010, at A18.

62. Kimberly Dozier, CIA Forms New Center To Combat Nukes, WMDs, A

SSOCIATED

PRESS REPORT, Aug. 18, 2010.

63. See A

NALYZING INTELLIGENCE: ORIGINS, OBSTACLES, AND INNOVATIONS (Roger Z.

George & James B. Bruce eds., 2008).

11_JOHNSON_V12_01-09-12.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE ) 2/9/2012 3:55 PM

2012] PLANNING FOR PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS 505

is likely to continue, leading to a more frequent melding of mind and

muscle whenever the United States turns to the use of PM operations.

Whether the result is success or failure, one thing is certain about PM

operations: they come to light at some point. Hoping to avoid potential

embarrassments for the United States caused by the disclosure of

paramilitary PM, William H. Webster crafted a set of questions that he

posed to SOG and other CA managers throughout his tenure as DCI from

1987 to 1991. The objective was to weed out, in advance, activities likely

to discredit the United States if revealed. Webster’s litmus test for planned

PM operations included these questions:

• Is the operation legal (with respect to U.S. law, not necessarily

international law)?

• Is the operation consistent with American foreign policy, and, if

not, why not?

• Is the operation consistent with American values?

• If the operation becomes public, will it make sense to the

American people?

64

Within these questions are embedded principles that ought to be in the

forefront of their thinking as Presidents, national security advisers, and

intelligence managers contemplate the adoption of paramilitary operations.

64. Staff interview with Judge William H. Webster, former DCI and FBI Director, led

by General Counsel John B. Bellinger III, Aspin-Brown Commission, in Washington, DC

(May 10, 1995). Similarly, former national security adviser McGeorge Bundy has said that

“if you can’t defend a covert action if it goes public, you’d better not do it at all – because it

will go public usually within a fairly short time span.” Interview with McGeorge Bundy,

Athens, Georgia (Oct. 6, 1987). Former DCI Stansfield Turner has also written: “There is

one overall test of the ethics of human intelligence activities. That is whether those

approving them feel they could defend their decisions before the public if their actions

became public.” S

TANSFIELD TURNER, SECRECY AND DEMOCRACY: THE CIA IN TRANSITION

178 (1985).